György Lukács facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

György Lukács

|

|

|---|---|

Lukács in 1952

|

|

| Born |

György Bernát Löwinger

13 April 1885 |

| Died | 4 June 1971 (aged 86) Budapest, Hungarian People's Republic

|

| Education | Royal Hungarian University of Kolozsvár (Dr. rer. oec., 1906) University of Berlin (1906–1907; no degree) Royal Hungarian University of Budapest (PhD, 1909) |

| Spouse(s) | Jelena Grabenko Gertrúd Jánosi (née Bortstieber) |

| Awards | Order of the Red Banner (1969) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neo-Kantianism (1906–1918) Western Marxism/Hegelian Marxism (after 1918) |

| Thesis | A drámaírás főbb irányai a múlt század utolsó negyedében (The Main Directions of Drama-Writing in the Last Quarter of the Past Century) (1909) |

| Doctoral advisor | Zsolt Beöthy (1909 PhD thesis advisor) |

| Other academic advisors | Georg Simmel |

| Doctoral students | István Mészáros, Ágnes Heller |

| Other notable students | György Márkus |

|

Main interests

|

Political philosophy, social theory, literary theory, aesthetics, Marxist humanism |

|

Notable ideas

|

Reification, class consciousness, transcendental homelessness, the genre of tragedy as an ethical category |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

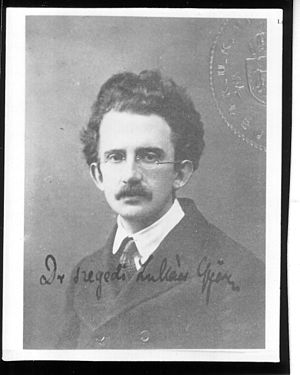

György Lukács (born György Bernát Löwinger; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was an important Hungarian philosopher, literary historian, and literary critic. He is known as one of the founders of Western Marxism. This was a way of thinking about Marxism that was different from the official Soviet ideas.

Lukács created the idea of reification. This means when human qualities or relationships turn into things. He also helped develop Karl Marx's idea of class consciousness. This is when people in a certain group understand their shared situation. He was also a philosopher who supported Leninism, which is based on the ideas of Vladimir Lenin.

As a critic, Lukács was very important for his ideas on literary realism. This is a style of writing that shows life as it really is. He also wrote a lot about the novel as a type of literature. In 1919, he became the Hungarian Minister of Culture. This was during the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic.

Contents

Who Was György Lukács?

Early Life and Education

György Lukács was born in Budapest, Austria-Hungary, on April 13, 1885. His birth name was György Bernát Löwinger. His family was wealthy and Jewish. His father was a banker who was later given a special title by the empire. This made Lukács a baron through inheritance. In 1907, he and his family changed their religion to Lutheranism.

Lukács was a very smart student. He studied at the Royal Hungarian University of Kolozsvár. There, he earned a doctorate in economic and political sciences in 1906. He also studied at the University of Berlin. In 1909, he finished his philosophy doctorate at the University of Budapest.

Becoming a Thinker and Writer

While at university, Lukács joined groups of thinkers who discussed socialist ideas. He met Ervin Szabó, who introduced him to the works of Georges Sorel. Lukács was interested in modern ideas and disliked positivism, which focused only on what could be proven.

From 1904 to 1908, he was part of a theater group. They put on modern plays that showed real human psychology. Between 1906 and 1909, he wrote a long book called History of the Development of the Modern Drama. It was published in Hungary in 1911.

Lukács spent a lot of time in Germany. He met famous philosophers like Georg Simmel and Max Weber. His ideas at this time were influenced by neo-Kantianism, Plato, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and others. During this period, he published Soul and Form (1911) and The Theory of the Novel (1916/1920).

In 1914, he married Jelena Grabenko, a Russian political activist. He was excused from military service during World War I. In 1915, he returned to Budapest. There, he led a group of intellectuals called the "Sunday Circle." They discussed cultural topics and hosted artists like Béla Bartók. By 1918, the group broke up because of different political views. Many members, including Lukács, joined the Communist Party of Hungary.

Political Journey and Communism

After World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1917, Lukács changed his mind about many things. He became a strong supporter of Marxism. In 1918, he joined the new Communist Party of Hungary. He had planned to move to Germany, but decided to stay in Hungary and pursue a political career.

Time in Government

When the Hungarian Soviet Republic was formed for a short time, Lukács became the People's Commissar for Education and Culture. This meant he was a minister in the government. After the Hungarian Soviet Republic was defeated, Lukács had to go into hiding. With help from a photographer, he escaped from Hungary to Vienna. He was arrested there but was saved from being sent back by a group of writers, including Thomas Mann.

In 1919, he married his second wife, Gertrúd Bortstieber. She was also a member of the Hungarian Communist Party.

Life During Difficult Times

In the 1920s, Lukács met other communists in Vienna. He started to develop his ideas about Leninism. His most important work from this time was History and Class Consciousness (1923). This book gave a strong philosophical base to Leninism. However, some communist leaders criticized his ideas.

After Vladimir Lenin's death, Lukács published a study called Lenin: A Study in the Unity of His Thought (1925). As a Hungarian exile, he stayed active in the Communist Party. He proposed new strategies for the party, but these were rejected. After this, he focused more on his theoretical writings.

In 1930, Lukács was called to Moscow. He was not allowed to leave the Soviet Union until after World War II. During Stalin's Great Purge, a time when many people were arrested or killed, Lukács was sent away for a while. However, he survived these dangerous times.

In 1945, Lukács and his wife returned to Hungary. He became a member of the Hungarian Communist Party and helped set up the new government. He also became a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

The 1956 Hungarian Revolution

In 1956, Lukács became a minister in the short-lived government led by Imre Nagy. This government was against the Soviet Union's control. Lukács believed the Hungarian Communist Party needed to work with other socialist groups. He thought they should slowly regain the trust of the Hungarian people.

After the revolution was defeated, Lukács was sent away to Romania with other government members. Unlike Nagy, he was not executed. Because of his role, the party no longer fully trusted him.

Lukács returned to Budapest in 1957. He publicly said he was wrong about his 1956 views. He remained loyal to the Communist Party until he died in 1971. In his last years, he became more openly critical of the Soviet Union.

Key Ideas and Writings

Lukács wrote many important books and essays. His work helped shape how people thought about Marxism, society, and literature.

Understanding Society: History and Class Consciousness

Lukács's book History and Class Consciousness was published in 1923. It brought new ideas to discussions about Marxism, society, and philosophy. This book started a new way of thinking called "Western Marxism."

One of the most important ideas in the book is "reification." In capitalist societies, human qualities and relationships can start to seem like things. These "things" then appear to control people's lives. Lukács explained that people themselves can become like objects, acting not as humans but according to the rules of this "thing-world." This idea helped explain parts of Karl Marx's theory of alienation.

Lukács also developed the Marxist idea of class consciousness. This is the difference between how a group of people actually lives and how much they understand their own situation. He believed that a group can only act successfully if its members understand their shared history and situation. This means they change from being a "class in itself" to a "class for itself."

Lukács on Books and Art

Lukács was also a very important literary critic. His early work, The Theory of the Novel, looked at the history of the novel. He explored what makes a novel unique. In this book, he used the term "transcendental homelessness." This describes a deep longing for a perfect place that people feel they once belonged to.

Later, Lukács said that The Theory of the Novel had some mistakes. But he also said it showed a "romantic anti-capitalism" that later led him to Marxism.

Lukács strongly disagreed with modern art styles like those of Franz Kafka and James Joyce. He preferred the traditional style of realism. He believed that realistic art showed life as it truly was.

Realism in Literature

Lukács believed that realistic literature connects human life to the whole of society. He saw two types of realism: critical and socialist. He argued that even writers with conservative political views, like Sir Walter Scott and Honoré de Balzac, could write great, realistic works. This was because they were critical of the rising capitalist society.

In his book The Historical Novel, Lukács looked at how historical fiction developed. He believed that after the French Revolution, people became more aware that history is always changing. This new awareness was shown in the novels of Sir Walter Scott. Scott used typical characters to show big social changes. Lukács thought that Scott's new historical realism influenced writers like Balzac and Tolstoy. These writers showed modern life as part of history, always changing.

Lukács believed that after the 1848 revolutions, historical realism started to decline. He thought that modernism, with its focus on style over substance, ignored history. He wanted writers to return to the realist tradition of Balzac and Scott.

Lukács also argued against "vulgar sociology" in literary criticism. This idea judged artists only by their social class. Lukács believed that great artists could rise above their class views. They could show the true connections between individuals and society.

He thought that all modernist art was the opposite of realism. He called it "decadent art." He believed that modernism failed to see the whole picture of society. For example, he said that Franz Kafka showed loneliness as a permanent part of human nature. But Lukács believed that loneliness should be shown as a result of capitalist society.

Lukács believed that socialist realism was a higher stage of art. He criticized some Soviet literature of the 1930s and 1940s. He said it was too simple and just propaganda. He thought it did not show the real conflicts of socialist society. Instead, it used bare ideas and ignored the details of real life.

Despite his criticisms, Lukács always believed that socialist realism was better than earlier forms of art. He even praised Alexander Solzhenitsyn as a great realist writer. Solzhenitsyn described life in prison camps. Lukács saw this as a sign of socialist realism coming back to life.

Ontology of Social Being

Later in his life, Lukács wrote a major work about the "ontology of social being." This work explored the nature of existence and society in a systematic way. It was a deep dive into dialectical philosophy.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Georg Lukács para niños

In Spanish: Georg Lukács para niños

- Lajos Jánossy, Lukács's adopted son

- Marx's notebooks on the history of technology

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |