Rosa Luxemburg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Rosa Luxemburg

|

|

|---|---|

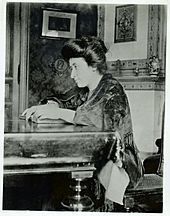

Luxemburg, c. 1895–1905

|

|

| Born |

Rozalia Luksenburg

5 March 1871 Zamość, Congress Poland, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 15 January 1919 (aged 47) |

| Alma mater | University of Zurich (Dr. jur., 1897) |

| Occupation |

|

| Political party |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Gustav Lübeck

(m. 1897, divorced) |

| Partner(s) |

|

| Signature | |

Rosa Luxemburg (born Rozalia Luksenburg; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was an important thinker and activist. She was a socialist and Marxist philosopher from Poland. She also worked hard for peace and against war.

Rosa was born into a Jewish family in Poland. Poland was then part of the Russian Empire. In 1897, she became a German citizen. She was a member of several political parties. These included the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).

During World War I, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht started the Spartacus League. This group was against the war. Later, it became the KPD. During the November Revolution, she helped start a newspaper called The Red Flag. This newspaper was important for the Spartacus movement.

Rosa Luxemburg was captured and killed by government-backed soldiers called the Freikorps. This happened during a revolt in January 1919. She is remembered as a brave figure who fought for her beliefs.

Contents

Who Was Rosa Luxemburg?

Early Life in Poland

Family and Childhood

Rosa Luxemburg was born Rozalia Luksenburg on 5 March 1871. She was born in Zamość, a town in Poland. At that time, Poland was divided and ruled by other countries. Her family was Polish Jewish. She was the youngest of five children.

Her father, Edward, was a businessman. He believed in liberalism, which means he supported freedom and equal rights. Her mother, Lina, loved to read. The family moved to Warsaw in 1873. At home, they spoke Polish and German. Rosa also learned Russian.

When she was five, Rosa had a hip problem. This left her with a permanent limp. Even with this, she was very smart. She loved poetry and impressed her family with her recitals.

School and Early Activism

In 1884, Rosa went to a secondary school for girls in Warsaw. This school mostly accepted Russian students. Polish and Jewish students were rarely allowed. Speaking Polish was forbidden because Russia wanted Poles to become more Russian.

But Rosa secretly joined groups that studied Polish writers. In 1886, she joined an illegal left-wing group called the Proletariat Party. She helped organize a big strike. Because of this, some leaders were killed. Rosa and other members kept meeting in secret.

In 1887, she finished school. The police wanted to arrest her for her political work. To escape, she fled to Switzerland in 1889.

Studying in Switzerland

In Switzerland, Rosa studied at the University of Zurich. She studied philosophy, history, politics, and economics. She focused on political science and economic crises. In 1897, she earned a Doctor of Law degree. Her paper was about Poland's industrial growth. She was one of the first women in the world to get a doctorate in economics.

In 1893, Rosa helped start a newspaper called The Workers' Cause. This paper was against Polish nationalist ideas. Rosa believed that Poland could only become independent through socialist revolutions in other countries. She thought the main fight should be against capitalism, not just for Polish independence.

She also helped create the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL) party. Even though she lived in Germany later, she was a main thinker for this Polish party. She loved Polish culture and hated the forced Germanization of Poles.

The 1905 Revolution

In 1905, a revolution started in Poland. Rosa went back to Warsaw, even though it was dangerous. She used a fake passport. She and her friend Leo Jogiches wrote for an illegal newspaper. Rosa was one of the first to see how this revolution could bring more democracy to the Russian Empire.

She wrote over 100 articles and speeches about the revolution. On 4 March 1906, she was arrested. She was held in different prisons in Warsaw. But she kept writing, and her work was secretly taken out of prison.

Her family bribed two officers, and she was released on bail. She then secretly fled to Germany in September 1906.

Moving to Germany

Rosa wanted to live in Germany to be at the center of political struggles. To get German citizenship, she married Gustav Lübeck in 1897. They never lived together and divorced five years later. She then moved to Berlin.

In Germany, she joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). She became friends with Clara Zetkin. Rosa believed that workers and minorities could only achieve freedom through revolution. She was known for her strong arguments.

Her letters show that she remained close with her family. She also identified as Polish and often disliked living in Germany. She saw it as a political necessity.

Before World War I

When Rosa moved to Berlin in 1898, she became active in the SPD. She strongly disagreed with Eduard Bernstein's ideas, which aimed to reform capitalism rather than overthrow it. She wrote a paper called Social Reform or Revolution? to argue against him.

Rosa was a powerful speaker. She argued that the difference between capital (money/resources) and labor (workers) could only be fixed if workers took power. She wanted big changes in how things were produced.

From 1900, Rosa wrote about Europe's social and economic problems. She saw war coming and strongly criticized German militarism (building up military power) and imperialism (extending a country's power). She wanted a general strike to stop the war. But SPD leaders disagreed.

She was jailed three times between 1904 and 1906 for her political activities. In 1907, she met Vladimir Lenin in London. At a socialist meeting in Stuttgart, her idea that all European workers' parties should unite to stop the war was accepted.

Rosa taught Marxism and economics at the SPD's training center in Berlin. Her student, Friedrich Ebert, later became Germany's first President. In 1912, Rosa argued that European workers should organize a general strike if war broke out. In 1913, she told a crowd: "If they think we are going to lift the weapons of murder against our French and other brethren, then we shall shout: 'We will not do it!'"

But when World War I started in 1914, there was no general strike. The SPD supported the war. This greatly frustrated Rosa. She organized anti-war protests in Frankfurt. She called for people to refuse military service. Because of this, she was jailed for a year.

-

Clara Zetkin and Rosa Luxemburg in 1910

During the War

In August 1914, Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht started the "International" group. This group became the Spartacus League in 1916. They wrote illegal anti-war pamphlets. They used the name Spartacus, after a famous gladiator who fought against the Romans. Rosa's pen name was Junius.

The Spartacus League strongly opposed the SPD's support for funding World War I. They urged German workers to go on an anti-war strike. As a result, Rosa and Liebknecht were imprisoned in June 1916 for two and a half years.

While in prison, Rosa continued to write. Friends secretly smuggled her articles out. One of her famous writings was The Russian Revolution. In it, she criticized the Bolsheviks for trying to create a totalitarian one-party state. She wrote: "Freedom is always the freedom of the one who thinks differently."

In 1917, the Spartacus League joined the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD). This party was made up of former SPD members who were against the war.

In November 1918, the USPD and SPD took power in the new Weimar Republic. This happened after the German Emperor stepped down. The German Revolution began with sailors rebelling. Workers' and soldiers' councils took control of most of Germany.

German Revolution of 1918–1919

Rosa Luxemburg was freed from prison on 8 November 1918. This was just three days before the end of World War I. The next day, Karl Liebknecht, also freed, declared a "Free Socialist Republic" in Berlin.

Rosa and Liebknecht reorganized the Spartacus League. They started The Red Flag newspaper. They demanded freedom for all political prisoners. They also wanted to end the death penalty. On 1 January 1919, they founded the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).

In January 1919, a second wave of revolution hit Berlin. Rosa and Liebknecht supported this attempt to overthrow the government. The Red Flag encouraged rebels to take over newspaper offices and other power centers. Rosa called for revolutionary action and no talks with the government.

Assassination and Aftermath

In response to the uprising, German Chancellor Friedrich Ebert ordered the Freikorps (paramilitary groups) to stop the revolution. The revolt was crushed by 11 January 1919.

Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were captured in Berlin on 15 January 1919. They were taken by the Freikorps. The officers in charge ordered their immediate execution. Rosa was hit on the head and shot. Her body was thrown into a canal. Liebknecht was also shot.

Their deaths marked the start of more violence in Berlin and Germany. Many other strikes and armed conflicts happened across the country.

Years later, some historians claimed that Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin ordered the killing of Russian Grand Dukes in retaliation for Rosa and Liebknecht's murders.

The officers involved in their deaths were not fully punished. Captain Waldemar Pabst, who gave the order, was never prosecuted. He later claimed that Defence Minister Gustav Noske and Chancellor Friedrich Ebert had secretly approved his actions.

Annual Demonstration

In Berlin, there is an annual demonstration called the Liebknecht-Luxemburg Demonstration. It happens in January around the date of their deaths. People march from Frankfurter Tor to their graves in the Zentralfriedhof Friedrichsfelde cemetery. This cemetery is also known as the Socialist Memorial.

In East Germany, this event was a big public display. During the Peaceful Revolution in 1989, East German activists used this parade to protest the government. They held banners with Rosa Luxemburg's famous quote: "True freedom is always the freedom of the non-conformists!"

In January 2019, German left-wing parties marked the 100th anniversary of their deaths.

Rosa Luxemburg's Ideas

Revolutionary Socialist Democracy

Rosa Luxemburg believed strongly in democracy and the need for revolution. She thought that workers should be able to free themselves. She also believed that a truly democratic society needed freedom of speech and assembly.

She criticized the early Russian Revolution for being undemocratic. She wrote: "Without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of press and assembly, without a free struggle of opinion, life dies out in every public institution." She believed that without these freedoms, public life would become dull and controlled by a small group of leaders.

The Accumulation of Capital

The Accumulation of Capital was Rosa's main book on economics. In it, she argued that capitalism always needs to grow. It needs to find new places to get resources, sell products, and find workers. She believed this constant need for expansion led to imperialism. This is when powerful countries take over weaker ones.

She thought that as capitalism expanded, it would destroy non-capitalist areas. Eventually, there would be no new markets left. This would cause capitalism to break down. Her ideas led her to fight against militarism and colonialism throughout her life.

Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organisation

A key part of Rosa's political ideas was the "Dialectic of Spontaneity and Organisation." This means that revolution should come from the people themselves (spontaneity). But it also needs to be organized by a political party. She believed these two things were not separate. They were different parts of the same process.

She developed these ideas after seeing the mass strikes during the Russian Revolution of 1905.

Criticism of the October Revolution

Rosa Luxemburg wrote about the Russian Revolution. She criticized some of the Bolsheviks' actions. For example, she disagreed with them closing the Russian Constituent Assembly in 1918. She also disagreed with their policy on national self-determination.

She believed the Bolsheviks' mistakes created dangers for the revolution. She thought these mistakes could lead to a government controlled by too many rules and officials. However, she also said that the problems of the Russian Revolution were small compared to the "complete failure of the international proletariat" to act.

Leaders like Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky responded to her criticisms. They argued that their actions were necessary for Russia at that time.

Famous Quotes

- "Freedom is always the freedom of the one who thinks differently."

- "The capitalist state of society is doubtless a historic necessity, but so also is the revolt of the working class against it – the revolt of its gravediggers." (April 1915)

- "Without general elections, without unrestricted freedom of press and assembly, without a free struggle of opinion, life dies out in every public institution, becomes a mere semblance of life, in which only the bureaucracy remains as the active element."

- "Today, we face the choice exactly as Friedrich Engels foresaw it a generation ago: either the triumph of imperialism and the collapse of all civilization as in ancient Rome, depopulation, desolation, degeneration – a great cemetery. Or the victory of socialism, that means the conscious active struggle of the international proletariat against imperialism and its method of war."

Legacy

Poland

Even though Rosa Luxemburg was Polish, her views on Polish independence have made her a debated figure in modern Poland.

During the time of the Polish People's Republic, a factory in Warsaw was named after her. Many streets in Polish cities were also named after her. Some still are today.

Efforts have been made to put up plaques in her memory in cities like Poznań and her birthplace, Zamość. In 2019, a sightseeing tour was organized in Warsaw about her life.

Germany

In 1919, the writer Bertolt Brecht wrote a poem honoring Rosa Luxemburg.

A famous monument to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht was built in Berlin in 1926. It was designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. The monument was destroyed by the Nazis in 1935.

In former East Germany and East Berlin, many places were named after Rosa Luxemburg. These include the Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz and a subway station. An engraving on the pavement nearby reads: "I was, I am, I will be."

After Germany reunified, some wanted to rename streets honoring communist figures. But a compromise was reached. Streets and squares in former East Berlin still bear Rosa Luxemburg's name.

A memorial has been placed near the Landwehr Canal in Berlin. It marks the spot where her body was thrown into the canal.

Elsewhere

Streets and squares in other countries are also named after Rosa Luxemburg. These include places in Ukraine, Russia, Belarus, Spain, and Austria.

In Barcelona, there are gardens named after her. In Madrid, there is a street and several schools and groups named after Luxemburg.

There is also a monument in Luxembourg called "Lady Rosa."

Many people, including feminists and Trotskyists, are still interested in Rosa Luxemburg's ideas. In 2002, ten thousand people marched in Berlin for Luxemburg and Liebknecht. Another 90,000 people placed flowers on their graves.

Works

- The Accumulation of Capital, 1913.

- The Accumulation of Capital: an Anticritique, 1915.

- Gesammelte Werke (Collected Works), 5 volumes, Berlin, 1970–1975.

- Gesammelte Briefe (Collected Letters), 6 volumes, Berlin, 1982–1997.

- Politische Schriften (Political Writings), 3 volumes, Frankfurt am Main, 1966 ff.

- The Complete Works of Rosa Luxemburg, 14 volumes, London and New York, 2011.

- The Rosa Luxemburg Reader, edited by Peter Hudis and Kevin B. Anderson.

Writings

This is a list of some of her writings:

| Writing | Year | Text | Translator | Year of English publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Industrial Development of Poland | 1898 | English | Tessa DeCarlo | 1977 |

| In Defence of Nationality | 1900 | English | Emal Ghamsharick | 2014 |

| Social Reform or Revolution? | 1900 | English | ||

| The Socialist Crisis in France | 1901 | English | ||

| Organizational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy | 1904 | English | ||

| The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions | 1906 | English | Patrick Lavin | 1906 |

| The National Question | 1909 | English | ||

| Theory & Practice | 1910 | English | ||

| The Accumulation of Capital | 1913 | English | Agnes Schwarzschild | 1951 |

| The Accumulation of Capital: An Anti-Critique | 1915 | English | ||

| The Junius Pamphlet | 1915 | English | ||

| The Russian Revolution | 1918 | English | ||

| The Russian Tragedy | 1918 | English |

Speeches

| Speech | Year | Transcript |

|---|---|---|

| Speeches to Stuttgart Congress | 1898 | English |

| Speech to the Hanover Congress | 1899 | English |

| Speech to the Nuremberg Congress of the German Social Democratic Party | 1908 | English |

See also

In Spanish: Rosa Luxemburgo para niños

In Spanish: Rosa Luxemburgo para niños

- Proletarian internationalism

- Rosa Luxemburg Foundation

- List of peace activists

- Clara Zetkin

- Nadezhda Krupskaya

- Alexandra Kollontai

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |