Alexandra Kollontai facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexandra Kollontai

|

|

|---|---|

| Алекса́ндра Миха́йловна Коллонта́й | |

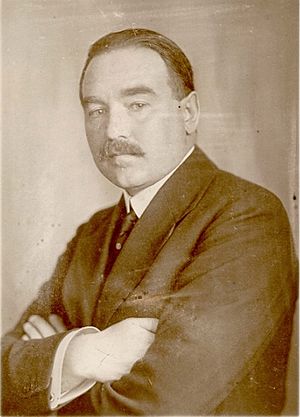

Kollontai, c. 1900

|

|

| Born |

Alexandra Mikhailovna Domontovich

31 March 1872 |

| Died | 9 March 1952 (aged 79) |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Occupation | professional revolutionary, writer, diplomat |

| Political party | VKP(b) |

| Spouse(s) | Vladimir Ludvigovich Kollontai Pavel Efimovich Dybenko |

| Children | Mikhail Vladimirovich Kollontai |

| Signature | |

|

|

Alexandra Mikhailovna Kollontai (Russian: Алекса́ндра Миха́йловна Коллонта́й, born Domontovich; 31 March 1872 – 9 March 1952) was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and diplomat. She was also a writer who thought deeply about Marxism, a political idea about how society should be organized.

In 1917–1918, she served as the People's Commissar for Welfare in Vladimir Lenin's government. This made her a very important woman in the Bolshevik party. She was also the first woman in history to become an official member of a country's governing cabinet.

Kollontai was the daughter of an army general. She became interested in radical politics in the 1890s and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in 1899. This party later split into two main groups: the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks.

She was sent away from Russia in 1908. During this time, she traveled around Europe and the United States. She spoke out strongly against countries joining World War I. In 1915, she decided to leave the Mensheviks and became a member of the Bolsheviks.

After the February Revolution in 1917, which removed the Tsar from power, Kollontai returned to Russia. She strongly supported Lenin's new ideas. As a member of the party's Central Committee, she voted for the armed uprising that led to the October Revolution. This event caused the fall of the Provisional Government.

She was then appointed People's Commissar for Social Welfare in the first Soviet government. However, she soon resigned because she disagreed with the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk. She was one of the few women who played a major role during the Russian Revolution.

In 1919, Kollontai started the Zhenotdel. This group worked to make life better for women in the Soviet Union. She was a strong supporter of women's liberation. Later, she became known as a key figure in Marxist feminism, which combines ideas about women's rights with Marxist principles.

Kollontai often spoke out against too much control by officials within the Communist Party. She also disliked how the party made decisions without involving everyone. Because of this, she joined a group called the Workers' Opposition in 1920. However, her ideas were not adopted, and she was almost removed from the party.

From 1922 onwards, she was given different jobs as a diplomat in other countries. She worked in Norway, Mexico, and Sweden. In 1943, she became the ambassador to Sweden. Kollontai stopped working as a diplomat in 1945 and passed away in Moscow in 1952.

Contents

Her Life Story

Family Background

Alexandra Kollontai's father, General Mikhail Alekseyevich Domontovich, came from a Ukrainian family. Her mother, Alexandra Alexandrovna Masalina, was the daughter of a Finnish peasant who became wealthy.

Her parents' journey to be together was long and difficult because of society's rules. This story greatly influenced Alexandra Kollontai's own ideas about relationships and marriage.

Growing Up

Alexandra Mikhailovna Domontovich was born on 31 March 1872 in St. Petersburg. She was called "Shura" by her family. She was very close to her father, sharing his interest in history and politics.

She was a good student and learned many languages. She spoke French, English, Finnish, and studied German. Alexandra wanted to go to university, but her mother thought women did not need higher education. Her mother also worried about radical ideas at universities. Instead, Alexandra was expected to become a teacher and then find a husband, as was common at the time.

Around 1890 or 1891, Alexandra met her cousin, Vladimir Ludvigovich Kollontai. He was an engineering student without much money. Alexandra's mother did not approve of their relationship because he was poor. But Alexandra said she would work as a teacher to help. Her mother doubted this, saying Alexandra was like a princess who never helped with chores.

Her parents tried to stop the relationship by sending Alexandra to Western Europe. However, Alexandra and Vladimir stayed together and married in 1893. Their son, Mikhail, was born in 1894. Alexandra spent her time reading political books and writing stories.

Becoming an Activist

Kollontai was first interested in ideas about changing society based on old village communities. But she soon found other revolutionary ideas. She was drawn to Marxism, which focused on factory workers, taking power, and building a modern industrial society.

Her first steps in activism were small. She helped her sister at a library that taught basic reading to city workers. They quietly shared socialist ideas during these lessons. Through this library, Kollontai met Elena Stasova, an early Marxist activist. Stasova began using Kollontai to deliver secret writings.

Years later, Kollontai wrote that she and Vladimir separated even though they loved each other. She felt trapped because of the revolutionary changes happening in Russia. In 1898, she left her son Mikhail with her parents. She went to Zürich, Switzerland, to study economics. She also visited England and met British socialists. She returned to Russia in 1899 and met Vladimir Lenin.

Kollontai joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party in 1899 when she was 27. In 1905, she saw the event known as Bloody Sunday in St. Petersburg. This was a popular uprising in front of the Winter Palace.

When the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party split into Mensheviks and Bolsheviks in 1903, Kollontai did not pick a side at first. But in 1906, she joined the Mensheviks because she disagreed with the Bolsheviks' actions regarding the Duma (a Russian assembly).

She went into exile in Germany in 1908 after writing a paper called "Finland and Socialism." This paper encouraged the Finnish people to fight against oppression. She traveled across Western Europe and met other important socialist thinkers like Clara Zetkin and Rosa Luxemburg.

In 1911, she became close with Alexander Gavrilovich Shliapnikov, another exile. Their romantic relationship ended in 1916, but they remained close friends. They shared many of the same political views.

When Russia entered World War I in 1914, Kollontai left Germany. She was strongly against the war and spoke out about it. In June 1915, she left the Mensheviks and officially joined the Bolsheviks. She saw them as the group most consistently fighting against support for the war.

After leaving Germany, Kollontai traveled to Denmark and then Sweden, where she was briefly imprisoned for her anti-war activities. She then went to Norway, where she found socialists who agreed with her. Kollontai stayed mostly in Norway until 1917. She visited the United States twice to speak about war and politics. In 1917, when she heard about the February Revolution, Kollontai returned to Russia.

The Russian Revolution

When Vladimir Lenin returned to Russia in April 1917, Kollontai was one of the few important Bolshevik leaders who immediately supported his new ideas. She was part of the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet. Throughout 1917, she actively promoted revolution in Russia through speeches, leaflets, and by working on the Bolshevik women's newspaper Rabotnitsa.

After an uprising against the Provisional Government in July, she was arrested with other Bolshevik leaders. But she was released in September. She was then a member of the party's Central Committee and voted for the armed uprising that led to the October Revolution.

On 26 October, she was chosen as the People's Commissar for Social Welfare in the first Soviet government. However, she soon resigned because she disagreed with the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk. During this time, at age 45, she married Pavel Dybenko, a 28-year-old revolutionary sailor. She kept her first husband's last name.

She was the most well-known woman in the Soviet government. She was famous for starting the Zhenotdel (Women's Department) in 1919. This group worked to improve women's lives in the Soviet Union. It fought against illiteracy and taught women about new laws for marriage, education, and work that came from the Revolution. The Zhenotdel was eventually closed in 1930.

In politics, Kollontai became more and more critical of the Communist Party. She spoke out against its undemocratic ways. In 1921, she publicly supported the Workers' Opposition. This group wanted workers to have more control over factories and the economy.

Kollontai wrote a famous pamphlet called The Workers' Opposition. In it, she criticized the party for becoming too bureaucratic and for not being truly focused on workers. Her words were very strong. Lenin was very upset about Kollontai joining this group. He felt she was trying to create a new party.

The Workers' Opposition group was eventually dissolved. Kollontai was largely pushed aside from her central political role. Despite this, she continued to try to speak out for her views. She warned that new economic policies might make workers unhappy and bring back capitalism.

Kollontai's final act of opposition within the Communist Party was signing a letter from 22 members. This letter asked the Communist International (a global organization of communist parties) to address the undemocratic practices in the Russian party. However, her efforts were not successful. At the next Party Congress, Kollontai and others were warned to stop their opposition.

Diplomatic Career

After the Eleventh Congress, Kollontai became less involved in internal party politics. She was worried about being expelled from the party. She also went through a difficult divorce from her second husband, Pavel Dybenko. She wanted a change.

In 1922, she wrote to Joseph Stalin, who was then a powerful leader. She asked to be sent on a mission abroad. Stalin agreed. From October 1922, she began to work as a diplomat in other countries. This meant she could no longer play a direct political role at home. She hoped it was only temporary, but it became a long-term assignment, almost like an exile.

She was first sent as an assistant to the Soviet trade mission in Norway. This made her one of the first women to serve in diplomacy in modern times. In 1924, she was promoted to Chargé d'affaires and then to Minister Plenipotentiary. She later worked in Mexico (1926–27), again in Norway (1927–30), and finally in Sweden (1930–45). In Sweden, she was promoted to Ambassador in 1943.

While Kollontai was in Stockholm, the Winter War broke out between Russia and Finland. It is believed that her influence helped Sweden stay neutral during this conflict. After the war, she received praise for her efforts. She also helped with peace talks. Kollontai retired from diplomatic service in 1945. In 1946 and 1947, she was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize for her work in ending the war between the Soviet Union and Finland.

Later Life and Legacy

Being sent abroad for over twenty years, Kollontai changed her approach. She stopped her strong fight for reforms and women's rights in the same way she had before. She accepted the new political situation. She did not object to new laws that changed some of the gains women had made after the revolutions.

Alexandra Kollontai passed away in Moscow on 9 March 1952, just before her 80th birthday. She was buried at Novodevichy Cemetery.

She was the only member of the Bolsheviks' Central Committee from the October Revolution who lived into the 1950s, besides Stalin himself. Some people have criticized her for not speaking out during the difficult political changes of the 1930s, when many of her friends and former colleagues were arrested or executed. However, it's also important to remember that she had to worry about her own family's safety.

In the 1960s and 1970s, with the rise of new social movements and feminism, people became very interested in Alexandra Kollontai's life and writings again. Many books and articles were published about her. Her story has also been featured in films and TV shows.

Ideas on Women's Rights

Kollontai is seen as a very important person in Marxist feminism. This is because she believed strongly in both women's liberation and Marxist ideas. She disagreed with liberal feminism, which she thought mainly helped wealthy women.

Kollontai believed that true women's liberation could only happen when society changed completely, with a new economic system. She criticized other feminists for focusing on political goals like women's suffrage (the right to vote). She felt these goals would help wealthy women but not improve the daily lives of working-class women.

Kollontai thought that the traditional family would eventually change a lot. She believed that marriage could continue, but it would need to become more equal. She imagined a marriage where partners were free from old, unequal roles. This would allow them to have relationships based on mutual love and trust.

She also thought that housework prevented women from being fully free. She believed that under communism, society would take care of many tasks that used to be done at home. This would free both men and women.

Kollontai's ideas about marriage and family under communism were very influential. She believed that the family unit, like the government, would become less important as communism fully developed. She saw traditional marriage and families as old ways that tied women to unpaid work at home, in addition to their jobs outside the home.

Kollontai encouraged people to let go of old ideas about family life. She said that mothers should think of all children as "our children, the children of Russia's communist workers." Under communism, both men and women would work for society and be supported by society, not just their families. Children would also be cared for by society. However, she also said that the joys of being a parent would not be taken away from those who appreciated them.

Awards

- Order of Lenin (1933)

- Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1945)

- Order of St. Olav (Norway's highest award at the time)

- Order of the Aztec Eagle (1944)

Works

- "The Social Basis of the Woman Question" (1909)

- "New Woman" (1913)

- Vasilisa Malygina (novel, 1923)

- Communism and the Family. (1970)

- Women Workers Struggle for their Rights. (1973)

- The Workers' Opposition. (1973)

- International Women's Day. (1974)

- Selected Writings of Alexandra Kollontai. (1977)

- Love of Worker Bees (novel, 1977)

- A Great Love (novel, 1981)

- Selected Articles and Speeches. (1984)

- The Essential Alexandra Kollontai. (2008)

- The Workers Opposition in the Russian Communist Party: The Fight for Workers Democracy in the Soviet Union. (2009)

See Also

In Spanish: Aleksandra Kolontái para niños

In Spanish: Aleksandra Kolontái para niños

- Zhenotdel

- Kommunistka

- History of feminism

- Women in the Russian Revolution