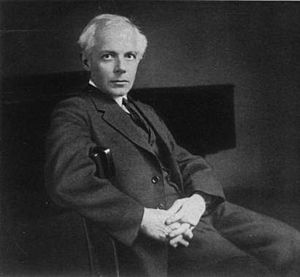

Béla Bartók facts for kids

Béla Viktor János Bartók (born March 25, 1881 – died September 26, 1945) was a famous Hungarian composer, pianist, and ethnomusicologist. An ethnomusicologist is someone who studies the music of different cultures. He is known as one of the most important composers of the 20th century. Many people consider him and Franz Liszt to be Hungary's greatest composers. He helped create the study of comparative musicology, which is now called ethnomusicology, by collecting and studying folk music.

Contents

Biography

Childhood and Early Years (1881–98)

Béla Bartók was born in a town called Nagyszentmiklós in Hungary (now Sânnicolau Mare, Romania) on March 25, 1881. His family had Hungarian roots. His mother, Paula, also spoke Hungarian.

Béla showed amazing musical talent very early. His mother said he could tell different dance rhythms apart on the piano even before he could speak full sentences. By age four, he could play 40 piano pieces, and his mother started teaching him formally the next year.

In 1888, when he was seven, his father passed away suddenly. His mother then moved with Béla and his sister, Erzsébet, to different towns. Béla gave his first public concert at age 11. People liked it a lot! He even played his own first song, written two years earlier, called "The Course of the Danube." Soon after, László Erkel became his teacher.

Early Musical Career (1899–1908)

From 1899 to 1903, Bartók studied piano and composition at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest. There, he met Zoltán Kodály, who became a close friend and colleague for life. In 1903, Bartók wrote his first big orchestral work, Kossuth, a symphonic poem honoring a Hungarian hero.

His early music was influenced by the composer Richard Strauss. In 1904, Bartók heard a young nanny singing folk songs. This moment made him want to study folk music for the rest of his life.

Starting in 1907, he was also influenced by the French composer Claude Debussy. Bartók began teaching piano at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest. This job allowed him to stay in Hungary and focus on his work. Many of his students became famous musicians themselves.

In 1908, he and Kodály traveled to the countryside to collect old Hungarian folk melodies. They found that these old songs were different from what people thought was "Gypsy music." Bartók and Kodály discovered that the old Hungarian folk melodies used special pentatonic scales, similar to music from Asia.

Bartók and Kodály started using these folk melodies in their own compositions. They often used parts of real folk songs or wrote whole pieces based on them. For example, Bartók wrote two books called For Children for solo piano, which have 80 folk tunes with his own piano parts. Bartók's music mixed folk music with classical and modern styles. He especially liked the unique rhythms and harmonies from Bulgarian music.

Middle Years and Career (1909–39)

Personal Life

In 1909, Bartók married Márta Ziegler. Their son, Béla Bartók III, was born the next year. After almost 15 years, they divorced in 1923. Two months later, he married Ditta Pásztory, who was a piano student. Their son, Péter, was born in 1924.

Bartók was very fond of nature. His son said he always spoke about the amazing order of nature with great respect.

Opera

In 1911, Bartók wrote his only opera, Bluebeard's Castle. He submitted it for a prize, but it was rejected. He revised the music for its first performance in 1918.

Folk Music and Composition

After his opera was rejected, Bartók spent a few years focusing on collecting and arranging folk music. He found the phonograph (an early record player) very helpful for recording folk music accurately. He collected music from Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria. He and Kodály used an Edison machine to record hundreds of folk songs. Bartók's deep understanding of folk music helped him create his unique musical style. He also collected music in Moldavia, Wallachia, and Algeria. World War I stopped his travels, but he returned to composing. He wrote a ballet called The Wooden Prince (1914–16) and his String Quartet No. 2 (1915–17).

Bartók's other ballet, The Miraculous Mandarin, was first performed in 1926. He also wrote two violin sonatas (1921 and 1922), which are very complex pieces.

In 1927–28, Bartók wrote his Third and Fourth String Quartets. After this, his music showed his mature style. Important works from this time include Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936) and Divertimento for String Orchestra (1939). He also wrote his Fifth String Quartet in 1934 and his last, the Sixth String Quartet, in 1939. In 1936, he traveled to Turkey to collect and study Turkish folk music.

World War II and Final Years (1940–45)

In 1940, as World War II made the situation in Europe worse, Bartók felt he had to leave Hungary. He was strongly against the Nazis and Hungary's alliance with Germany. Because of his anti-fascist views, he had problems with the government in Hungary. He refused to perform in Germany after 1933.

After sending his music papers out of the country, Bartók and his wife, Ditta Pásztory, moved to the U.S. in October 1940. They settled in New York City. Their younger son, Péter, joined them in 1942 and later served in the United States Navy. His older son, Béla Bartók III, stayed in Hungary.

Even though he became an American citizen in 1945, Bartók never felt completely at home in the United States. He found it hard to compose at first. He was known as a pianist and a music researcher, but not as much as a composer. There wasn't much interest in his music during his last years. He and Ditta gave some concerts, but not many. Bartók also made recordings for Columbia Records.

He and Ditta worked on a large collection of Serbian and Croatian folk songs at Columbia University. Bartók's money situation was sometimes difficult, but he was not poor. He had friends and supporters who helped him. He was a proud man and didn't like to accept help easily.

In late 1940, Bartók started having health problems. In 1942, he had fevers. In April 1944, doctors found he had leukemia, a type of cancer. By then, it was too late to do much.

Even as his health failed, Bartók found new creative energy. He wrote some of his greatest works, thanks to friends like violinist Joseph Szigeti and conductor Fritz Reiner. His last work might have been the String Quartet No. 6, but then he was asked to write the Concerto for Orchestra. This piece was first performed in December 1944 and became very popular.

In 1944, he also wrote a Sonata for Solo Violin for Yehudi Menuhin. In 1945, Bartók composed his Piano Concerto No. 3 as a surprise birthday gift for Ditta, but he passed away just over a month before her birthday, with the music almost finished. He had also started his Viola Concerto, but only finished the viola part and some notes for the orchestra.

Béla Bartók died at age 64 in a New York City hospital on September 26, 1945, due to complications from leukemia. Only ten people attended his funeral.

Bartók was first buried in New York. In 1988, the Hungarian government and his two sons asked for his remains to be moved back to Budapest. He received a state funeral in Hungary on July 7, 1988, and was re-buried next to Ditta, who had passed away in 1982.

His unfinished works were completed by his student Tibor Serly.

Music

Bartók's music shows two big changes in 20th-century music. First, it moved away from the traditional harmony system. Second, it brought back nationalism as a source of musical ideas. Bartók looked to Hungarian folk music, and also music from other parts of Europe and even Algeria and Turkey, to find new sounds. This made him very important in modern music that uses local traditions.

One special style in his music is called "Night music." He used it in slow parts of his larger pieces. It sounds "eerie" with strange harmonies, like sounds of nature and lonely melodies. An example is the third part of his Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta. His music can be grouped by different periods of his life.

Early Years (1890–1902)

Bartók's early works were in a classical and early romantic style, with some influences from popular and Romani music. Between ages nine and 13, he wrote 31 piano pieces. Even though many were simple dances, he started trying more advanced forms. He played one of these, "The Course of the Danube," at his first public concert.

In school, Bartók studied music from Bach to Wagner. His own compositions started to sound like Schumann and Brahms. In 1902, he was very excited by the music of Richard Strauss, especially his piece Also sprach Zarathustra. Bartók said it showed him "the way that lay before me."

New Influences (1903–11)

Influenced by Strauss, Bartók composed Kossuth in 1903, a piece about the 1848 Hungarian war for independence. This showed his growing interest in national music. In 1904, hearing a nanny sing Transylvanian folk songs made him dedicate his life to folk music. Bartók started collecting Hungarian peasant melodies, and later folk music from Slovaks, Romanians, and others. His music slowly removed romantic elements and focused more on folk music.

Bartók learned about Debussy's music in 1907 and admired it. Debussy's influence can be heard in Bartók's Fourteen Bagatelles (1908). Until 1911, Bartók wrote many different kinds of works, from romantic styles to folk song arrangements and his modern opera Bluebeard's Castle. When his work wasn't well received, he focused more on folk music research and less on composing new pieces, except for folk arrangements.

Inspiration and Experimentation (1916–21)

Bartók started composing again around 1915. He wrote the Suite for piano (1916), The Miraculous Mandarin (1918), and finished The Wooden Prince (1917).

Bartók felt that World War I was a personal tragedy. Many areas he loved were separated from Hungary. This also made it harder for him to research folk music outside of Hungary. Bartók also wrote the important Eight Improvisations on Hungarian Peasant Songs in 1920, and the cheerful Dance Suite in 1923.

"Synthesis of East and West" (1926–45)

In 1926, Bartók needed a major piece for piano and orchestra so he could tour. He was inspired by American composer Henry Cowell's use of "tone clusters" on the piano (playing many notes very close together at once). Bartók asked Cowell for permission to use this technique, and Cowell agreed. To prepare for his first Piano Concerto, Bartók wrote his Sonata, Out of Doors, and Nine Little Pieces, all for solo piano, which use these clusters. He found his unique voice as he got older. The style of his last period is a mix of different influences. In his mature period, Bartók wrote fewer works, but most were large pieces for big groups of instruments.

Among Bartók's most important works are his six string quartets (written between 1909 and 1939), the Cantata Profana (1930), Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (1936), the Concerto for Orchestra (1943), and the Third Piano Concerto (1945). He also made a lasting contribution for young students: for his son Péter's music lessons, he composed Mikrokosmos, a six-volume collection of piano pieces that get harder as you go along.

Catalogues

Cataloguing Bartók's works can be a bit tricky. He tried to number his works three times, but stopped because it was hard to tell his original pieces from his folk music arrangements, or big works from small ones. After he died, people created new ways to list his music. The most common one uses "Sz." numbers (from 1 to 121). Another one uses "BB." numbers (from 1 to 129).

On January 1, 2016, Bartók's works became part of the public domain in the European Union. This means his music can be used and performed freely without needing special permission or paying royalties.

Discography

Bartók and his friend Zoltán Kodály did a lot of research to record folk melodies from Hungary, Slovakia, and Romania. At first, they wrote the melodies down by hand. Later, they used a wax cylinder recording machine invented by Thomas Edison. Recordings of Bartók's field recordings, interviews, and his own piano playing have been released by the Hungarian record label Hungaroton.

- Bartók, Béla. 1994. Bartók at the Piano. Hungaroton 12326. 6-CD set.

- Bartók, Béla. 1995a. Bartók Plays Bartók – Bartók at the Piano 1929–41. Pearl 9166. CD recording.

- Bartók, Béla. 1995b. Bartók Recordings from Private Collections. Hungaroton 12334. CD recording.

- Bartók, Béla. 2003. Bartók Plays Bartók. Pearl 179. CD recording.

- Bartók, Béla. 2003. Bartók Sonata for 2 Pianos & Percussion, Suite for 2 Pianos. Apex 0927-49569-2. CD recording.

- Bartók, Béla. 2007. Bartók: Contrasts, Mikrokosmos. Membran/Documents 223546. CD recording.

- Bartók, Béla. 2008. Bartók Plays Bartók. Urania 340. CD recording.

- Bartók, Béla. 2016. Bartók the Pianist. Hungaroton HCD32790-91. Two CDs. Works by Bartók, Domenico Scarlatti, Zoltán Kodály, and Franz Liszt.

In 2016, Decca Classics released Béla Bartók: The Complete Works, which is the first full collection of all his compositions.

Statues

- A statue of Bartók stands in Brussels, Belgium, in a public square.

- Another statue is outside Malvern Court, London. An English Heritage blue plaque also marks the house where he stayed in London.

- A statue of him is in front of the house where Bartók lived his last eight years in Hungary, in Budapest. This house is now the Béla Bartók Memorial House. Copies of this statue are also in Makó, Paris, London, and Toronto.

- A bust (a sculpture of his head and shoulders) and a plaque are at his last home in New York City, at 309 W. 57th Street.

- A bust of him is in the front yard of the Ankara State Conservatory in Turkey.

- A bronze statue of Bartók, made by Imre Varga in 2005, is in the lobby of The Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto, Canada.

- A statue of Bartók, also by Varga, is near the river Seine in a public park in Paris, France.

- In the same park, there's a fountain/sculpture called Cristaux that shows his ideas about music.

- An expressionist sculpture by Hungarian sculptor András Beck is in another park in Paris.

- A statue of him also stands in the city center of Târgu Mureș, Romania.

- A seated statue of Bartók is in front of Nako Castle, in his hometown, Nagyszentmiklós.

See also

In Spanish: Béla Bartók para niños

In Spanish: Béla Bartók para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |