Richard Strauss facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Richard Strauss

|

|

|---|---|

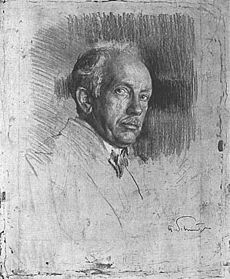

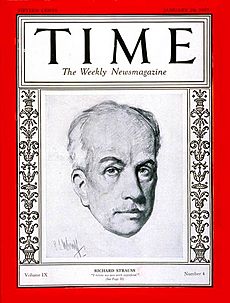

Portrait of Strauss by Max Liebermann (1918)

|

|

| Born |

Richard Georg Strauss

11 June 1864 Munich, Kingdom of Bavaria, German Confederation

|

| Died | 8 September 1949 (aged 85) |

| Resting place | Strauss Villa |

| Occupation |

|

|

Works

|

List of compositions, especially operas and tone poems |

| Spouse(s) |

Pauline de Ahna

(m. 1894) |

| Children | Franz Strauss |

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

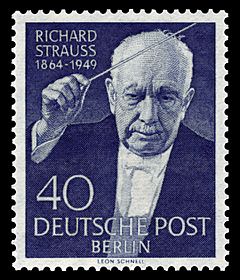

Richard Georg Strauss (born June 11, 1864 – died September 8, 1949) was a famous German composer and conductor. He also played the piano and violin. People saw him as a top composer of the late Romantic and early modern music periods. Many thought he followed in the footsteps of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt.

Strauss started composing music when he was just six years old in 1870. He continued writing music almost until he died nearly eighty years later. He wrote many types of classical music. But he was most famous for his tone poems (orchestral pieces that tell a story) and operas (musical plays).

Some of his most famous tone poems include Don Juan, Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks, and Also sprach Zarathustra. His opera Salome made him internationally famous. He also wrote many successful operas with a writer named Hugo von Hofmannsthal. These include Elektra and Der Rosenkavalier.

Strauss was also a very important conductor in Europe and America. He was admired for leading works by other composers like Mozart and Wagner. He also conducted his own music. He held important conducting jobs at major opera houses in Munich, Weimar, Berlin, and Vienna. He even helped start the Salzburg Festival.

Contents

Richard Strauss's Life

His Early Life and Music (1864–1886)

Richard Strauss was born in Munich on June 11, 1864. His father, Franz Strauss, was a main horn player at the Munich Court Opera. His mother, Josephine, came from a wealthy brewing family.

Richard started learning music at age four. He took piano lessons and soon began attending orchestra rehearsals. He wrote his first song when he was six. He also learned violin and studied composition for five years. After high school, he spent one year at the University of Munich.

His father greatly influenced his musical journey. The Strauss home was always full of music. His father taught him about composers like Beethoven and Mozart. He also helped Richard with his compositions. His father even let Richard's early symphonies be played by an amateur orchestra he conducted. This helped Richard develop his skills.

At first, Richard's father did not want him to study Wagner's music. Wagner's music was seen as too modern and risky. But Richard heard Wagner's operas and was deeply impressed. He later regretted that his father was so against Wagner's new style.

In 1882, Richard played his own Violin Concerto in Vienna. The same year, he went to Berlin. There, he became an assistant conductor for the Meiningen Court Orchestra. He learned a lot about conducting by watching his mentor, Hans von Bülow. Strauss called Bülow his greatest conducting teacher.

When Bülow left in 1885, Strauss became the main conductor for a few months. He helped prepare for the first performance of Johannes Brahms's Symphony No. 4. Brahms himself conducted it. Strauss also conducted his own Symphony No. 2 for Brahms.

Becoming a Famous Conductor and Tone Poet (1885–1898)

In 1885, Strauss met Alexander Ritter, a composer and violinist. Ritter convinced Strauss to try a new, more modern style of composing. He encouraged Strauss to follow the ideas of Wagner and Liszt. This led Strauss to start writing tone poems. These are orchestral pieces that tell a story or describe something.

After leaving Meiningen, Strauss traveled in Italy. He wrote down his travel experiences and musical ideas. These became his first tone poem, Aus Italien (1886). He then became a conductor at the Bavarian State Opera in Munich. He found the work there boring because he wanted to stage more exciting operas.

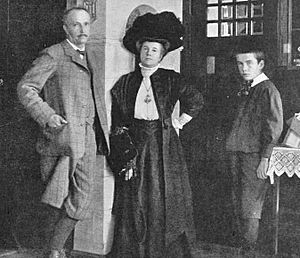

During this time, Strauss met his future wife, Pauline de Ahna, a singer. He became her main voice teacher. They married on September 10, 1894. Pauline was known for being strong-willed and outspoken. But their marriage was happy, and she inspired much of his music. Strauss loved writing for the soprano voice (a high female voice). Many of his operas have important soprano roles.

In 1889, Strauss became the main conductor in Weimar. This was a very successful time for him. His tone poem Don Juan premiered in 1889 and brought him international fame. Then came Death and Transfiguration in 1890. These works made him a leading modern composer.

In 1894, Strauss conducted at the Bayreuth Festival for the first time. His wife Pauline sang in the opera. He then became the first conductor of the Bavarian State Opera. Over the next four years, he wrote many more famous tone poems. These include Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks (1895), Also sprach Zarathustra (1896), and Ein Heldenleben (1898). In 1897, his only child, Franz, was born. In 1906, Strauss bought land and built a villa in Garmisch-Partenkirchen where he lived until he died.

Opera Success and Global Fame (1898–1933)

In 1898, Strauss became the main conductor of the Berlin State Opera. He held this position for 15 years. By now, he was a very famous conductor. He was often invited to conduct all over the world. He was especially known for conducting works by Wagner, Mozart, and Liszt, as well as his own music.

His own compositions were becoming very popular. In 1901, the Vienna Philharmonic played a whole concert of only his music. In 1903, festivals dedicated to his music were held in London and Heidelberg.

In 1904, Strauss toured North America for the first time. He conducted the first performance of his Symphonia Domestica in New York City. During this trip, he was busy composing his third opera, Salome. This opera, based on a play by Oscar Wilde, premiered in 1905. It was a huge success and was soon performed in opera houses worldwide.

After Salome, Strauss created many successful operas with the writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal. These include Elektra (1909), Der Rosenkavalier (1911), and Die Frau ohne Schatten (1919). Der Rosenkavalier is often considered his greatest opera. He continued to conduct internationally. From 1919 to 1924, he was the main conductor of the Vienna State Opera. In 1920, he helped create the Salzburg Festival.

When World War I started, Strauss was asked to sign a statement supporting Germany's role in the war. He refused, saying that artists should focus on their creations, not politics. In 1924, his son Franz married Alice von Grab-Hermannswörth. Alice was from a Jewish family. Franz and Alice had two sons, Richard and Christian.

During Nazi Germany (1933–1945)

In 1933, when Strauss was 68, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power. Strauss never joined the Nazi Party. He tried to avoid Nazi greetings and politics. However, he decided to cooperate with the new government at first. He hoped Hitler, who loved music, would support German art.

A very important reason for his cooperation was to protect his Jewish daughter-in-law, Alice, and his Jewish grandchildren. He also wanted to keep the music of banned composers, like Mahler, being performed. Strauss privately disliked Joseph Goebbels, a powerful Nazi official. But he dedicated a song to Goebbels to try and extend copyright laws for composers.

In 1933, Strauss took over as director of the Bayreuth Festival. The previous director, Arturo Toscanini, had resigned to protest the Nazi government. Strauss tried to ignore Nazi bans on music by composers like Debussy and Mendelssohn. He also continued to work on an opera, Die schweigsame Frau, with his Jewish friend and writer Stefan Zweig. When the opera premiered in 1935, Strauss insisted Zweig's name be shown. This angered the Nazi regime. The opera was stopped after only three performances and then banned.

Because of this, Strauss was removed from his position as president of the Reich Music Chamber in 1935. However, his Olympische Hymne, which he wrote in 1934, was used at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. Many people criticized Strauss for his actions during this time. But much of what he did was to protect his family. He used his influence to prevent his grandsons and their mother from being sent to dangerous places.

Later Operas and Family Challenges

Strauss could no longer work with Zweig. So he started working with Joseph Gregor, a historian. Their opera Friedenstag (Peace Day) premiered in 1938, just before World War II began. This opera was a clear message for peace and against violence. It was a subtle criticism of the Nazi Party. Productions of the opera stopped soon after the war started. They worked on two more operas: Die Liebe der Danae (1940) and Capriccio (1942).

In 1938, his daughter-in-law Alice was put under house arrest. Strauss used his connections to keep her safe. He even tried to get Alice's grandmother released from a camp, but he was not successful. Sadly, many of Alice's relatives were killed in the camps.

In 1942, Strauss moved his family to Vienna. There, Alice and her children could be better protected. But in early 1944, Alice and her son Franz were taken by the Gestapo. Strauss personally stepped in and saved them. He brought them back to Garmisch, where they stayed under house arrest until the war ended.

Metamorphosen and the End of the War

In 1945, Strauss finished Metamorphosen, a piece for 23 string instruments. He wrote this music during the darkest days of World War II. It shows his sadness over the destruction of German culture, including the bombing of many great opera houses.

In April 1945, American soldiers found Strauss at his home in Garmisch. He famously told a U.S. Army lieutenant, "I am Richard Strauss, the composer of Rosenkavalier and Salome." The lieutenant, who was also a musician, recognized him. An "Off Limits" sign was put on his lawn to protect him. An American oboist in the army asked Strauss to write an oboe concerto. Strauss completed this beautiful Oboe Concerto later that year.

His Final Years and Death (1942–1949)

The last years of Strauss's life, from 1942 until his death, were very creative. He wrote major works even in his late 70s and 80s. These include his Horn Concerto No. 2, Metamorphosen, his Oboe Concerto, and his Four Last Songs.

After the war, Strauss's bank accounts were frozen. He and his wife moved to Switzerland in October 1945. In 1947, he went on his last international tour to London. He conducted several of his works. This trip was a great success and helped him and his wife financially.

From May to September 1948, just before he died, Strauss composed the Four Last Songs. These songs are about dying. The last one ends with the question, "Is this perhaps death?" He answers this by quoting a theme from his earlier tone poem Death and Transfiguration. This symbolizes the soul's journey after death. In June 1948, a tribunal in Munich cleared him of any wrongdoing during the Nazi era.

In December 1948, Strauss had surgery and his health got worse. He conducted his last performance on June 10, 1949, for his 85th birthday. He died peacefully in his sleep on September 8, 1949, in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. He famously said from his deathbed, "dying is just as I composed it in Tod und Verklärung" (Death and Transfiguration). His wife, Pauline, died eight months later.

Strauss once said, "I may not be a first-rate composer, but I am a first-class second-rate composer." But many people, like the pianist Glenn Gould, called him "the greatest musical figure who has lived in this century."

Richard Strauss's Music

Solo and Chamber Works

Strauss's first compositions were for solo instruments or small groups of instruments. These included early piano pieces, two piano trios, a string quartet, and a cello sonata.

After 1890, he wrote less for small groups. He focused more on large orchestral works and operas. Some of his later chamber pieces were actually arrangements from his operas. His last independent chamber work was for violin and piano in 1948. He also wrote two large works for wind instruments in the 1940s.

Tone Poems and Other Orchestral Works

Strauss wrote two early symphonies. But his style truly changed after he met Alexander Ritter in 1885. Ritter encouraged him to write tone poems. These pieces tell a story or describe a scene using music. Ritter also introduced him to the ideas of Wagner.

This new influence led to Don Juan (1888). This piece showed his new, exciting orchestral style. He then wrote a series of even bigger tone poems: Death and Transfiguration (1889), Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks (1895), Also sprach Zarathustra (1896), and Ein Heldenleben (1898). These works are still very popular with orchestras today.

Concertos

Strauss wrote many works for a solo instrument with an orchestra. His most famous include two concertos for horn. These are still played by horn soloists worldwide. He also wrote a Violin Concerto (1882), a Burleske for piano and orchestra (1885), and the famous Oboe Concerto (1945). His Duett-Concertino for clarinet, bassoon, and string orchestra was one of his last pieces.

Opera

Around the late 1800s, Strauss started focusing on opera. His first two operas, Guntram (1894) and Feuersnot (1901), were a bit controversial. Guntram was his first big failure.

In 1905, Strauss created Salome. This opera was based on a play by Oscar Wilde. It was very modern and used some harsh sounds for the time. But it was a huge success! The audience loved it, and the performers took many curtain calls. Many people say Strauss paid for his house in Garmisch-Partenkirchen with the money from Salome.

His next opera was Elektra (1909). This opera used even more unusual harmonies. Elektra was also his first collaboration with the writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal. They worked together many times after that. For their later operas, Strauss used a more beautiful, melodic style. This led to very popular operas like Der Rosenkavalier (1911).

Strauss continued to write operas regularly until 1942. With Hofmannsthal, he created Ariadne auf Naxos (1912), Die Frau ohne Schatten (1919), and Arabella (1933). For Intermezzo (1924), Strauss wrote both the music and the story himself. His final opera, Capriccio (1942), was written with Clemens Krauss.

Lieder (Songs)

Strauss wrote many lieder (songs). He often composed them with his wife's voice in mind. These songs were for voice and piano, and he later added orchestra to some of them. In 1894–1895, he published several famous songs like "Ruhe, meine Seele!" and "Morgen!".

After focusing on operas for a long time, he wrote more songs in 1918. He finished his songs in 1948 with the Four Last Songs for soprano and orchestra. These songs are very popular and are considered masterpieces.

Richard Strauss's Legacy

Strauss is known for his amazing orchestral writing and advanced harmonies. One conductor, Mark Elder, said that when he first played Strauss's music, he was "flabbergasted" by what the music could do with harmony and melody.

Strauss's music greatly influenced other composers in the early 20th century. Composers like Béla Bartók and Karol Szymanowski were inspired by his works. English composers like Edward Elgar and Benjamin Britten also showed his influence. Many modern composers still feel a debt to Strauss.

Strauss's musical style also played a big role in developing film music. His way of showing characters and emotions in music found its way into movie scores. Composers like Max Steiner and Erich Wolfgang Korngold used his style in their film music. The famous opening of Also sprach Zarathustra was used in the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. The music of John Williams (who wrote for Star Wars) also shows Strauss's influence.

Strauss's music has always been popular with audiences. He is consistently one of the most performed composers by orchestras in the US and Canada. He also has many recordings of his works available today.

Recordings as a Conductor

Strauss made many recordings as a conductor. He recorded his own music and works by other German and Austrian composers. His 1929 recordings of Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks and Don Juan are considered some of his best early recordings.

In 1944, for his 80th birthday, Strauss conducted the Vienna Philharmonic in recordings of his major orchestral works. These recordings were made using early tape recording equipment. Some people find these later performances more emotional than his earlier ones. His very last recording was in London in 1947.

Strauss also made recordings for player pianos. He was even the composer whose music was on the first CD ever sold commercially in 1983. The conductor Pierre Boulez called Strauss "a complete master of his trade" as a conductor.

Fun Stories

In 1891, Strauss was very sick with pneumonia. He wrote to a friend, "Dying may not be so bad, but I should first like to conduct Tristan."

In 1934, Strauss told his friend Stefan Zweig, "What suits me best... are sentimental jobs." He added that amazing pieces like the Rosenkavalier trio don't happen every day. He wondered if he had to be seventy to realize his greatest strength was in creating "kitsch" (art that is popular but not considered high art).

In 1948, his son Franz visited him and told him to stop worrying and write some nice songs instead. A few months later, Strauss gave his daughter-in-law Alice some scores. He said, "Here are the songs your husband ordered." These were the Four Last Songs.

Richard Strauss's Ibach Piano

This image shows a 1907 Ibach Model 2 grand piano. It has a cherry wood case with a checkerboard design. The music stand has a criss-cross pattern. This piano was one of two almost identical pianos offered to Richard Strauss. Strauss chose the other one, which had lower sides. He wanted his audience to see his hands when he played at home concerts. This piano (number 56278) stayed with the Ibach company for exhibitions.

Honors and Awards

Strauss received many honors during his life, including:

- 1903: Honorary Doctorate from Heidelberg University.

- 1907: Croix de Chevalier (Knight's Cross) of the Legion of Honour from France.

- 1910: Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art.

- 1914: Honorary Doctorate from Oxford University. He also became an honorary citizen of Munich.

- 1924: Pour le Mérite for Sciences and Art, a German award.

- 1924: Honorary Doctorate from the University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna. He also received the Freedom of the cities of Vienna and Salzburg.

- 1932: New York College of Music Medal.

- 1936: The Royal Philharmonic Society's gold medal.

- 1939: Commandeur de L'Ordre de la Couronne (Commander of the Order of the Crown) from Leopold III of Belgium.

- 1949: Honorary Doctorate from the University of Munich.

See also

In Spanish: Richard Strauss para niños

In Spanish: Richard Strauss para niños