Glenn Gould facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Glenn Gould

|

|

|---|---|

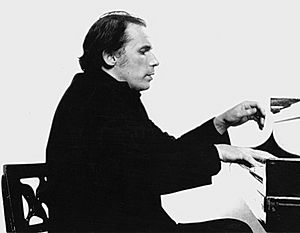

Gould in later years

|

|

| Born |

Glenn Herbert Gold

September 25, 1932 |

| Died | October 4, 1982 (aged 50) Toronto, Ontario, Canada

|

| Burial place | Mount Pleasant Cemetery |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Alma mater | Royal Conservatory of Music |

| Occupation |

|

|

Notable work

|

Performances of Bach's keyboard works |

| Parents |

|

| Awards | Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award (2013) Grammy, 1973, 1982 Juno Award, 1979 Canadian Music Hall of Fame National Historic Person Companion of the Order of Canada (declined by Gould) |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | classical music |

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1945–1982 |

| Labels | CBS Records |

| Associated acts | Ellen Faull, Donald Gramm, Yehudi Menuhin, Leonard Rose, and others |

| Signature | |

Glenn Herbert Gould (born Gold; September 25, 1932 – October 4, 1982) was a famous Canadian classical pianist. He was one of the most celebrated pianists of the 20th century. Gould was especially known for playing the keyboard music of Johann Sebastian Bach. His playing was very skilled and clear, especially in music where different melodies weave together, like in Bach's pieces.

Gould preferred music by Bach and Beethoven. He also liked some later Romantic and modern composers. Even though he recorded a lot of Bach and Beethoven, he also played music by Mozart, Haydn, and Brahms. He also explored older music from before the Baroque period and music from the 20th century. Gould was known for his unique ways of playing and living. He stopped performing live concerts at age 31 to focus on recording music in a studio and other projects.

Besides being a pianist, Gould was also a writer, a radio host, a composer, and a conductor. He wrote many articles about music theory and his ideas about music. He performed on TV and radio. He also created three special radio documentaries about quiet, isolated parts of Canada. Even though he was famous as a pianist, he ended his musical career by conducting a recording of a piece by Wagner.

Contents

Life Story of Glenn Gould

Growing Up and Early Talent

Glenn Herbert Gould was born in Toronto, Canada, on September 25, 1932. He was the only child of Russell and Florence Gold. His family later changed their last name to Gould around 1939. This was done to avoid being mistaken for Jewish during a time when there was unfair treatment towards Jewish people.

Glenn showed an early interest in music and was very talented at the piano. Both his parents loved music. His mother, Florence, especially helped him develop his musical skills from a very young age. She even played music for him before he was born. She later taught him how to play the piano. As a baby, he would hum instead of crying and move his fingers as if playing piano chords. This led his doctor to guess he would become a doctor or a pianist.

He learned to read music before he could read words. By age three, he had perfect pitch, meaning he could identify musical notes just by hearing them. When he first got a piano, young Glenn would hit single notes and listen carefully as their sound slowly faded away. This was different from how most children played. Glenn was also interested in writing his own music. He would play his compositions for family, friends, and sometimes larger groups. In 1938, he performed one of his own pieces at a church.

When he was six, Glenn heard a famous musician play live. This experience had a big impact on him.

At age 10, he started studying at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Toronto. He learned music theory, organ, and piano. Around this time, he hurt his back after falling from a boat ramp. This injury is thought to be why his father later made him a special adjustable chair. Glenn's mother always told him to sit up straight at the piano. He used this special chair for the rest of his life, taking it with him almost everywhere he played. The chair allowed him to sit very low, which helped him press down on the keys instead of hitting them from above. This was a key idea from his piano teacher, Alberto Guerrero.

Gould developed a playing style that let him play very fast while keeping each note clear and separate. Sitting very low at the piano gave him more control over the keys. He showed great skill in playing and recording many different types of music. This included complex and expressive pieces, like his own version of Ravel's La valse. He also played Liszt's piano versions of Beethoven's Fifth and Sixth Symphonies. From a young age, Gould worked with Guerrero on a technique called finger-tapping. This method helped his fingers move more independently from his arm.

Gould passed his final piano exam at the Conservatory when he was 12. He got the highest score of all the students, becoming a professional pianist. A year later, he passed his written music theory exams.

Gould's Approach to the Piano

Gould was a child prodigy, meaning he had amazing talent from a young age. As an adult, he was called a musical genius. He often said he almost never practiced on the piano itself. Instead, he preferred to learn new music by reading it. This was another technique he learned from his teacher, Guerrero. However, he might have been joking about not practicing. There is evidence that he did practice hard sometimes, using his own special exercises.

Gould said he didn't understand why other pianists felt they needed to practice many hours a day. He seemed able to practice just by thinking about the music. For example, he once prepared to record piano pieces by Brahms without touching a piano until a few weeks before the recording sessions. Gould could play a huge amount of piano music from memory. He could "memorize at sight," meaning he could learn music just by looking at it. He once challenged a friend to name any piece of music he couldn't play instantly from memory.

Gould said the piano itself wasn't his favorite instrument. But he had played it his whole life, and it was the best way for him to share his musical ideas. For Bach's music, Gould changed the piano's keys to make them shallower and more responsive. He said this made the piano feel like a car without power steering: "you are in control and not it." He believed this control was key to playing Bach on the piano.

As a teenager, Gould was greatly influenced by pianists Artur Schnabel and Rosalyn Tureck, and conductor Leopold Stokowski. Gould was known for his strong imagination. Listeners thought his performances were either incredibly creative or very unusual. His piano playing was very clear and smart, especially in parts where different melodies played together. He also had amazing control. Gould believed the piano was best for playing music with multiple melodies. He felt that much of the music that came after the Baroque period was less serious.

Gould didn't like playing music in a showy or overly emotional way. He felt that this kind of playing was superficial. He thought that public concerts often became like a competition. He believed the audience was sometimes more interested in finding mistakes than truly listening to the music. He called this a "blood sport." Because of these feelings, he eventually decided to stop performing live concerts.

Public Performances

On June 5, 1938, at age five, Gould played in public for the first time. He joined his family on stage at a church service in Uxbridge, Ontario, playing piano for about 2,000 people. In 1945, at 13, he played with an orchestra for the first time. He performed part of Beethoven's 4th Piano Concerto with the Toronto Symphony. His first solo concert was in 1947. His first radio concert was with the CBC in 1950. This was the start of Gould's long connection with radio and recording. In 1953, he started a chamber music group called the Festival Trio.

In 1957, Gould toured the Soviet Union. He was the first North American musician to play there since World War II. His concerts included music by Bach, Beethoven, and modern composers like Schoenberg. These modern pieces had been restricted in the Soviet Union. Gould made his American TV debut on CBS in 1960. He played Bach's Keyboard Concerto No. 1 with Leonard Bernstein conducting.

Gould believed that public concerts were old-fashioned and even "a force of evil." He thought they turned into a competition where the audience looked for mistakes. This led him to stop performing live. On April 10, 1964, Gould gave his last public performance in Los Angeles. He played pieces by Beethoven, Bach, and Hindemith. During his career, Gould performed fewer than 200 concerts. Most of these were in Canada.

One of Gould's main reasons for stopping live performances was his love for the recording studio. He called it a "love affair with the microphone." In the studio, he could control every part of the final music. He could choose the best parts from different takes to create a perfect performance. He felt he could truly bring a musical piece to life this way. Gould believed there was no point in re-recording old pieces unless the musician had something new to say about them. For the rest of his life, he focused on recording, writing, and broadcasting instead of live shows.

Gould's Unique Habits

Gould was well-known for his unusual habits. He often hummed or sang while he played the piano. Sometimes, the sound engineers couldn't remove his voice from the recordings. Gould said his singing was unconscious. He felt it happened more when he struggled to play a piece exactly as he wanted. His biographer, Kevin Bazzana, wrote that the habit likely started because his mother taught him to "sing everything that he played." This became a habit he couldn't break. Some of Gould's recordings were criticized because of his background "vocalizing." For example, a reviewer of his 1981 recording of the Goldberg Variations said many listeners would find his groans and hums "intolerable."

Gould also had peculiar body movements while playing. He insisted on having complete control over his surroundings. The temperature in the recording studio had to be just right; he always wanted it to be very warm. According to another of Gould's biographers, Otto Friedrich, the air-conditioning engineer had to work as hard as the recording engineers.

The piano also had to be at a specific height. It would be raised on wooden blocks if needed. Sometimes, a rug was required for his feet. He had to sit exactly 14 inches above the floor. He would only play concerts using the special chair his father had made for him. He used this chair even when the seat was completely worn out. His chair is so famous that it is displayed in a glass case at Library and Archives Canada.

Conductors had different reactions to Gould and his playing habits. George Szell, who conducted with Gould in 1957, called him "a genius." Leonard Bernstein said, "There is nobody quite like him, and I just love playing with him." Bernstein caused a stir at a concert in 1962. Before the New York Philharmonic played Brahms's Piano Concerto No. 1 with Gould, Bernstein told the audience he wasn't responsible for what they were about to hear. He asked, "In a concerto, who is the boss—the soloist or the conductor?" The audience laughed. Bernstein was referring to their rehearsals, where Gould insisted on playing the first movement at half the normal speed.

Gould disliked cold weather. He wore heavy clothes, including gloves, even in warm places. He was once stopped by police in Florida, possibly mistaken for a homeless person. He was sitting on a park bench dressed in his usual coat, hat, and mittens. He also avoided social gatherings. He hated being touched. In his later life, he mostly communicated by phone and letters.

In his notes and radio shows, Gould created over two dozen fake characters. He used these characters for fun, satire, and teaching. They allowed him to write funny or confusing reviews of his own performances. Some well-known characters were Karlheinz Klopweisser, a German music expert, and Sir Nigel Twitt-Thornwaite, an English conductor. These parts of Gould's personality, whether seen as unusual behavior or just play, have given many writers material to study his life.

Gould did not cook. He often ate at restaurants and ordered room service. He usually ate one meal a day, along with arrowroot biscuits and coffee. In his later years, he said he was a vegetarian. However, his private notes sometimes listed foods like chicken and roast beef. Fran's Restaurant in Toronto was a favorite spot for Gould. A CBC report noted that "sometime between two and three every morning, Gould would go to Fran's... sit in the same booth, and order the same meal of scrambled eggs."

Health and Passing

Gould often worried about his health, even though he was known to be a hypochondriac (someone who worries too much about being sick). He had many aches and pains. However, his autopsy showed few serious problems in the areas that often bothered him. He worried about everything from high blood pressure to the safety of his hands. Gould rarely shook hands and usually wore gloves. The back injury he had as a child led doctors to prescribe him various pain relievers and other medicines. Some experts believe that Gould's increasing use of different prescription drugs might have harmed his health over time.

Some people have wondered if Gould's behavior was related to autism spectrum conditions. There has also been talk that he might have had bipolar disorder. This is because he sometimes went days without sleep, had bursts of energy, drove carelessly, and later in life experienced severe sadness.

On September 27, 1982, two days after his 50th birthday, Gould had a severe headache. He then suffered a stroke that paralyzed the left side of his body. He was taken to Toronto General Hospital, and his condition quickly worsened. By October 4, there was clear evidence of brain damage. Gould's father decided that his son should be taken off life support.

Gould's public funeral was held on October 15 at St. Paul's Anglican Church. Over 3,000 people attended, and the service was broadcast on the CBC. He is buried next to his parents in Toronto's Mount Pleasant Cemetery. The first few notes of the Goldberg Variations are carved on his grave marker. Gould loved animals and left half of his estate to the Toronto Humane Society. The other half went to the Salvation Army.

In 2000, a doctor specializing in movement disorders suggested that Gould had dystonia. This is a condition that causes uncontrolled muscle movements and was not well understood during Gould's lifetime.

Gould's Ideas and Views

His Writings

Gould sometimes told interviewers that he would have been a writer if he hadn't become a pianist. He shared his thoughts on music and art in lectures, speeches, magazines, and CBC radio and TV shows. Gould did many interviews, but he often planned them out so carefully that they were almost like written works. Gould's writing style was very clear and expressive, but sometimes a bit fancy or overly dramatic. This was especially true when he tried to be funny or ironic. While his writing offered "brilliant insights," it could also be difficult to read with "long, tortuous sentences."

In his writings, Gould praised certain composers and criticized what he saw as boring music. He also analyzed the music of Richard Strauss, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern. Although he liked some Dixieland jazz, Gould generally disliked popular music. He once criticized the Beatles for "bad voice leading" (how different musical parts move together). However, he praised singers like Petula Clark and Barbra Streisand. Gould and jazz pianist Bill Evans admired each other's work. Evans even made one of his famous recordings using Gould's special Steinway piano.

His View on Art

Gould's view on art is often summed up by this quote from 1962: "The purpose of art is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenaline but is, rather, the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity." This means he believed art should create a deep, lasting feeling of peace and amazement, not just a quick burst of excitement.

Gould often called himself "the last puritan". This was a reference to a novel by philosopher George Santayana. But in many ways, Gould was very forward-thinking. He promoted modern composers from the early 20th century. He also predicted how much technology would change how music is made and shared.

Technology and Music

There has been much discussion about whether Gould's way of making music was "authentic." Some wondered if a recording was less real because it was carefully put together in a studio. Gould compared his process to that of a film director. Just as a two-hour movie isn't made in two hours, he asked why recording music should be different. He even did an experiment where musicians, engineers, and regular people listened to a recording and tried to find where the edits were made. Everyone chose different spots, but no one was completely right. Gould joked, "The tape does lie, and nearly always gets away with it."

In one of his most important essays, "Forgery and Imitation in the Creative Process," Gould clearly shared his ideas about authenticity and creativity. He questioned why the time period a work was created in affects how it's seen as "art." He imagined a sonata he composed that sounded so much like a Haydn piece that it was thought to be one. If the sonata was then said to be by an earlier or later composer, it became more or less interesting. But the music itself didn't change, only its place in music history. Gould also pointed out how people reacted differently to high-quality fake paintings by Han van Meegeren that were thought to be by Johannes Vermeer, before and after the fakes were discovered.

Gould preferred to look at art without focusing too much on history. He thought that the artist's identity and the historical time period shouldn't be the main things used to judge a work of art. He asked, "What gives us the right to assume that in the work of art we must receive a direct communication with the historical attitudes of another period?"

Recordings and Collaborations

In the Studio

When making music, Gould much preferred the control and privacy of the recording studio. He disliked concert halls, which he compared to a sports arena. He gave his last public performance in 1964. After that, he focused his career on the studio, recording albums and several radio documentaries. He was interested in the technical side of recording. He thought that editing tape was another part of the creative process. Even though Gould's producers said he needed less editing than most musicians, he used the process to have complete artistic control over his recordings. He once explained how a fugue from Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier was put together from two different takes.

Gould's first professional recording was in 1953. He soon signed with Columbia Records. In 1955, he recorded Bach: The Goldberg Variations, which became his breakthrough work. This record received amazing praise and was one of the best-selling classical music albums of its time. Gould became strongly linked with this piece, playing it often in his concerts. A new recording of the Goldberg Variations in 1981 was one of his last albums. This piece was one of the few he recorded twice in the studio. The 1981 version was one of CBS Masterworks' first digital recordings. The 1955 recording is very lively, while the later one is slower and more thoughtful. Gould wanted to treat the piece as a complete work.

Gould said Bach was "first and last an architect, a constructor of sound." He called Bach "the greatest architect of sound who ever lived." He recorded most of Bach's other keyboard works. This included both books of The Well-Tempered Clavier, the partitas, French Suites, English Suites, and keyboard concertos. For his only organ recording, he played parts of The Art of Fugue. This was also released on piano after he passed away.

For Beethoven, Gould preferred the composer's early and late music. He recorded all five of Beethoven's piano concertos and many of his piano sonatas. Gould was the first pianist to record Liszt's piano versions of Beethoven's symphonies.

Gould also recorded music by Brahms, Mozart, and many other famous piano composers. However, he often criticized the Romantic music period as a whole. He was very critical of Chopin. When asked if he wanted to play Chopin, he said, "No, I don't. I play it in a weak moment—maybe once a year or twice a year for myself. But it doesn't convince me." But in 1970, he played Chopin's B minor sonata for the CBC. He said he liked some of Chopin's smaller pieces and "sort of liked the first movement of the B minor."

Although he recorded all of Mozart's sonatas and enjoyed playing them, Gould disliked Mozart's later works. He was fond of some less famous composers, like Orlando Gibbons. He heard Gibbons's music as a teenager and felt a "spiritual attachment" to it. He recorded several of Gibbons's keyboard works and called him his favorite composer, even more than Bach. He also recorded piano music by Jean Sibelius, Georges Bizet, Richard Strauss, and Hindemith. He recorded all of Schoenberg's piano works. In early September 1982, Gould made his final recording: Strauss's Piano Sonata in B minor.

Working with Others

The success of Gould's collaborations depended on whether his partners were open to his sometimes unusual ways of playing music. His TV collaboration with American violinist Yehudi Menuhin in 1965 was a success. They played works by Bach, Beethoven, and Schoenberg. Menuhin was willing to explore the new ideas Gould brought. However, his 1966 recording with soprano Elisabeth Schwarzkopf was considered a "fiasco." Gould recorded with many singers, including Donald Gramm and Ellen Faull. He also recorded Bach's sonatas for violin and harpsichord with Jaime Laredo. He recorded the sonatas for viola da gamba and keyboard with Leonard Rose. Claude Rains narrated their recording of Strauss's Enoch Arden. Gould also worked with members of the New York Philharmonic. He recorded Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 with flutist Julius Baker and violinist Rafael Druian. He also performed Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 5 with Leopold Stokowski and the American Symphony Orchestra in 1966.

Radio and TV Documentaries

Gould made many TV and radio programs for CBC Television and CBC Radio. A notable series was his musique concrète Solitude Trilogy. This series included The Idea of North, which was about Northern Canada and its people. The Latecomers was about Newfoundland. The Quiet in the Land was about Mennonites in Manitoba. All three used a special radio technique Gould called "contrapuntal radio." In this technique, several people speak at once, like voices in a fugue. Their voices were mixed and edited together. In 1967, Gould was driving across northern Ontario and listening to Top 40 radio. This inspired one of his most unusual radio pieces, The Search for Petula Clark. It was a clever and well-spoken discussion about Clark's recordings.

Another one of Gould's CBC programs was an educational lecture about Bach's music, called "Glenn Gould On Bach." It included a performance of the Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 with Julius Baker and Oscar Shumsky.

Compositions and Conducting

Gould also wrote many of his own versions of orchestral music for piano. He transcribed his own Wagner and Ravel recordings. He also transcribed operas by Strauss and symphonies by Schubert and Bruckner. He played these privately for fun.

Gould tried his hand at composing, but he finished few works. As a teenager, he wrote chamber music and piano pieces in the style of the Second Viennese school. Important works include a string quartet, which he finished in his 20s. He also wrote his own cadenzas (solo parts) for Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 1. Later works include the Lieberson Madrigal and So You Want to Write a Fugue? His String Quartet received mixed reviews. There isn't much critical writing about Gould's compositions because there are so few of them. He never wrote beyond his first published work and left many pieces unfinished. He felt he failed as a composer because he didn't have his own "personal voice." Most of his work is published by Schott Music. The recording Glenn Gould: The Composer contains his original works.

Towards the end of his life, Gould started conducting. He had previously conducted Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 and a cantata. His last recording as a conductor was of Wagner's Siegfried Idyll. He planned to spend his later years conducting, writing about music, and composing.

Gould's Legacy and Honors

Glenn Gould is considered one of the most famous musicians of the 20th century. His unique piano playing style, his deep understanding of how music was built, and his free way of interpreting musical scores created performances and recordings that amazed some listeners and were disliked by others. Philosopher Mark Kingwell wrote that Gould's influence is impossible to ignore. Every musician after him must either follow his example or reject it, but they cannot pretend he didn't exist.

One of Gould's performances of a piece from Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier was chosen to be included on the NASA Voyager Golden Record. This record was placed on the spacecraft Voyager 1. On August 25, 2012, the spacecraft became the first to leave our solar system and enter space between the stars.

Gould is a popular topic for books and studies. Philosophers have explored his life and ideas. There are many references to Gould and his work in poems, stories, and visual art. François Girard's 1993 film Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould includes interviews with people who knew him, acted-out scenes from his life, and imaginative animated parts set to music. Thomas Bernhard's 1983 novel The Loser is about Gould and his friendship with two other piano students.

Gould left behind a large amount of work beyond his piano playing. After he stopped giving concerts, he became more interested in other media. This included audio and film documentaries and writing. Through these, he thought about art, composing, music history, and how technology affected how people experienced music. Gould grew up in Toronto at the same time that Canadian thinkers like Marshall McLuhan were making important discoveries about communication. Collections of Gould's writings and letters have been published. Library and Archives Canada holds many of his personal papers.

In 1983, Gould was honored by being added to the Canadian Music Hall of Fame after his death. He was also added to Canada's Walk of Fame in Toronto in 1998. In 2012, he was named a National Historic Person. A special plaque was put up next to a sculpture of him in downtown Toronto. The Glenn Gould Studio at the Canadian Broadcasting Centre in Toronto is named after him. To celebrate what would have been Gould's 75th birthday, the Canadian Museum of Civilization held an exhibit called Glenn Gould: The Sounds of Genius in 2007.

The Glenn Gould Foundation

The Glenn Gould Foundation was started in Toronto in 1983. Its goal is to honor Gould and keep his memory and work alive. The foundation wants to spread awareness of Glenn Gould as an amazing musician and Canadian. It also aims to promote his forward-thinking ideas. The foundation's main activity is giving out the Glenn Gould Prize every three years. This prize goes to a person who has made a very special contribution to music and how it is shared, using any communication technologies. The winner receives CA$100,000 and gets to choose a young musician to receive the CA$15,000 Glenn Gould Protégé Prize.

The Glenn Gould School

The Royal Conservatory of Music Professional School in Toronto changed its name to The Glenn Gould School in 1997. This was done to honor its most famous former student.

Awards and Recognition

Gould received many honors during his life and after his death. In 1970, the Canadian government offered him the Companion of the Order of Canada, but he politely turned it down. He felt he was too young for such a high honor.

Juno Awards

The Juno Awards are given out every year by the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Gould won three Juno Awards. He accepted one of them in person.

| Year | Award | Nominated work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Best Classical Album of the Year | Hindemith: Das Marienleben (with Roxolana Roslak) | Won |

| 1981 | Best Classical Album of the Year | Bach Toccatas, Vol. 2 | Nominated |

| 1982 | Best Classical Album of the Year | Bach: Preludes. Fughettas & Fugues | Nominated |

| 1983 | Best Classical Album of the Year | Haydn: The Six Last Sonatas | Nominated |

| Bach: The Goldberg Variations | Won | ||

| 1984 | Best Classical Album of the Year | Brahms: Ballades Op. 10, Rhapsodies Op. 79 | Won |

Grammy Awards

The Grammys are given out every year by the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Gould won four Grammys. Like with the Junos, he accepted one in person. In 1983, he was added to the Grammy Hall of Fame after his death for his 1955 recording of the Goldberg Variations.

| Year | Award | Nominated work | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Best Album Notes – Classical | Hindemith: Sonatas for Piano (Complete) | Won |

| 1982 | Best Classical Album | Bach: The Goldberg Variations (with producer Samuel H. Carter) | Won |

| Best Instrumental Soloist Performance (without orchestra) |

Bach: The Goldberg Variations | Won | |

| 1983 | Best Classical Performance – Instrumental Soloist or Soloists (without orchestra) |

Beethoven: Piano Sonatas Nos. 12 & 13 | Won |

| 2013 | Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award | Won |

See also

In Spanish: Glenn Gould para niños

In Spanish: Glenn Gould para niños

- Gould Estate v Stoddart Publishing Co Ltd

- List of Canadian composers

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |