Anton Bruckner facts for kids

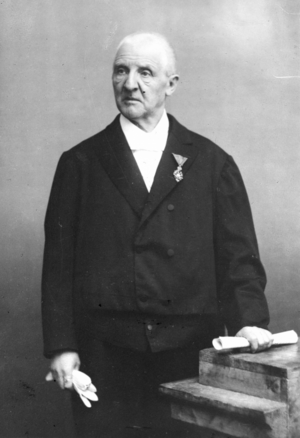

Josef Anton Bruckner (born September 4, 1824 – died October 11, 1896) was an Austrian composer and organist. He is most famous for his symphonies and religious music, which includes Masses, Te Deum, and motets. His symphonies are known for their rich sound, many layers of melodies playing together (called polyphony), and long length. Bruckner's music was quite new for his time, using unusual sounds and sudden changes in harmony.

Unlike other bold composers like Richard Wagner, Bruckner was very humble. People sometimes described him as "half genius, half simpleton." Bruckner was also very critical of his own music. He often changed his compositions, so many of his works have several different versions.

Some people, especially the critic Eduard Hanslick, did not like Bruckner's music. They thought his symphonies were too long and repeated too much. They also didn't like that he kept changing his works. However, many later composers, like his friend Gustav Mahler, greatly admired Bruckner.

Contents

Life and Career

Early Life

Anton Bruckner was born in Ansfelden, Austria, on September 4, 1824. His family had been farmers and craftspeople for centuries. His grandfather and father were schoolmasters in Ansfelden. This job didn't pay much, but it was respected. Anton was the oldest of eleven children.

Music was part of school, and Bruckner's father was his first music teacher. Anton learned to play the organ very early. He loved the instrument and would practice for many hours a day. He started school at six and was a hard-working student. He also helped his father teach other children.

In 1833, after his confirmation, Bruckner went to another school in Hörsching. The schoolmaster, Johann Baptist Weiß, was a great organist. Here, Bruckner finished school and became even better at playing the organ. Around 1835, he wrote his first piece, a Pange lingua.

Becoming a Teacher

Bruckner's father died in 1837 when Anton was 13. Anton was sent to the Augustinian monastery in Sankt Florian to be a choirboy. There, he also took violin and organ lessons. He loved the monastery's huge organ, which was later called the "Bruckner Organ."

Even with his musical talent, Bruckner's mother sent him to a teaching school in Linz in 1841. After he finished with excellent grades, he became a teacher's assistant in Windhaag. The pay and living conditions were very bad, and his boss often made him feel small. Despite this, Bruckner never complained. He stayed there for two years, teaching subjects that were not music.

A church leader, Michael Arneth, saw Bruckner's difficult situation. He gave him a better teaching job near Sankt Florian, in Kronstorf. This was a much happier time for Bruckner. From 1843 to 1845, he studied with Leopold von Zenetti in Enns. His music from this time showed much improvement and the start of his unique "Bruckner style."

Organist in Sankt Florian

After Kronstorf, Bruckner returned to Sankt Florian in 1845. For the next 10 years, he worked as a teacher and organist. In 1848, he became the official organist in Sankt Florian. He continued to study and improve his skills. Most of the music played there was by older composers like Michael Haydn.

Study Period

In 1855, Bruckner wanted to study with the famous music expert Simon Sechter in Vienna. He showed Sechter his Missa solemnis, a Mass he wrote a year earlier, and was accepted. He learned a lot about music theory and counterpoint (how different melodies fit together). Sechter's teaching greatly influenced Bruckner.

Bruckner mostly taught himself how to compose. He only started composing seriously at age 37, in 1861. He also studied with Otto Kitzler, who was younger than him. Kitzler introduced him to the music of Richard Wagner, which Bruckner studied deeply from 1863. Bruckner thought his early orchestral works were just practice exercises.

He continued his studies until he was 40. He didn't become widely famous until he was over 60, after his Seventh Symphony was first performed in 1884. In 1861, he met Franz Liszt, another composer who, like Bruckner, was very religious and explored new harmonies. In May 1861, Bruckner performed his own Ave Maria for the first time. After finishing his studies, he wrote his first important work, the Mass in D Minor.

The Vienna Period

In 1868, after Sechter died, Bruckner took over his teaching job at the Vienna Conservatory. During this time, he focused most of his energy on writing symphonies. These symphonies were not always well-received; some people called them "wild" or "nonsensical."

He later took a job at the University of Vienna in 1875. He tried to make music theory a bigger part of the university's courses. Overall, he was not happy in Vienna. The city's music scene was heavily influenced by the critic Eduard Hanslick. There was a rivalry between supporters of Wagner's music and those of Johannes Brahms. By siding with Wagner, Bruckner accidentally made Hanslick his enemy.

However, Bruckner also had supporters. Music critic Theodor Helm and famous conductors like Arthur Nikisch and Franz Schalk tried to make his music popular. They even suggested "improvements" to make his music more acceptable. Bruckner allowed these changes, but he also made sure in his will that his original scores would be kept safe in the Austrian National Library. He was confident that his original music was valid.

Besides his symphonies, Bruckner wrote Masses, motets, and other religious choral works. He also wrote a few chamber works, like a string quintet. While some of his choral works were traditional, pieces like the Te Deum and Psalm 150 showed new and bold uses of harmony.

Many people describe Bruckner as a "simple" man from the countryside. Biographers often note that his quiet life doesn't seem to match the grandness of his music. For example, after a rehearsal of his Fourth Symphony in 1881, Bruckner gave the conductor Hans Richter a coin. Richter said, "When the symphony was over, Bruckner came to me, his face beaming with enthusiasm and joy. I felt him press a coin into my hand. 'Take this,' he said, 'and drink a glass of beer to my health.'" Richter kept the coin as a souvenir.

Bruckner was a famous organist. He impressed audiences in France in 1869 and in the United Kingdom in 1871. He gave many recitals on new organs in London. Even though he didn't write many major pieces for the organ, his improvisations (making music up on the spot) sometimes gave him ideas for his symphonies. He taught organ at the Conservatory, and his students included Hans Rott and Franz Schmidt. Gustav Mahler, who called Bruckner his "forerunner," also attended the conservatory at this time.

In July 1886, the Emperor honored him with the Order of Franz Joseph. He likely retired from his university job in 1892, when he was 68. He wrote a lot of music that he used to help teach his students.

Death

Bruckner died in Vienna in 1896 at the age of 72. He is buried in the crypt (an underground room) of the monastery church at Sankt Florian, right below his favorite organ.

The Anton Bruckner Private University for Music, Drama, and Dance in Linz, near his hometown, was named after him in 1932. The Bruckner Orchestra Linz was also named in his honor.

Compositions

Bruckner's works are sometimes referred to by WAB numbers. This comes from the Werkverzeichnis Anton Bruckner, which is a list of all his works.

Bruckner often created several versions of his pieces. Some people believe he revised his works because of harsh criticism from others. Music expert Deryck Cooke wrote that Bruckner lacked confidence in these matters and felt he had to listen to his friends, who he saw as "experts." However, others argue that Bruckner often started a new symphony just days after finishing the previous one, showing his strong drive to compose. The reasons for his changes are still debated today.

Style

Bruckner's symphonies use a fairly standard orchestra. This includes woodwinds (like flutes and clarinets), four horns, two or three trumpets, three trombones, a tuba, timpani (kettledrums), and strings. His later symphonies use a few more instruments, like Wagner tubas. Only his Eighth Symphony uses a harp and other percussion besides timpani.

Some critics in Vienna didn't like how Bruckner wrote for the orchestra. But later, experts realized that his orchestral writing was inspired by the sound of his main instrument, the pipe organ. He would often switch between groups of instruments, much like an organist changes between different parts of the organ.

Structure

Bruckner's symphonies are usually in four movements, similar to those of Beethoven.

- The first movement is often fast (an allegro). It usually starts quietly with strings and builds up to a loud section. It has three main musical ideas or themes. The second theme is often like a song, and the third is very rhythmic. This movement often ends with a powerful coda (a concluding section).

- The second movement is usually slow (an adagio). It often has a song-like melody. In some symphonies, like his Eighth and Ninth, the slow movement is placed third.

- The scherzo is usually a lively and energetic movement. It often has a contrasting middle section called a trio, which is more melodic. In some of his symphonies, like the revised Fourth Symphony, the scherzo is known as the "Hunt scherzo."

- The Finale is the last movement, and it's also usually fast. Like the first movement, it has three main musical ideas. It often starts with an introduction. The development section is often very dramatic. The movement ends with a powerful coda, where themes from the first movement often return and are played grandly. In the coda of his Eighth Symphony, themes from all four movements are brought back together.

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Anton Bruckner para niños

In Spanish: Anton Bruckner para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |