Eduard Hanslick facts for kids

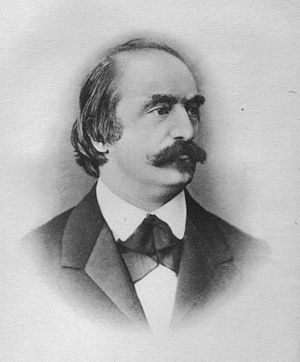

Eduard Hanslick (born September 11, 1825 – died August 6, 1904) was an important Austrian music critic and historian. He was one of the leading critics of his time, serving as the main music critic for the newspaper Neue Freie Presse from 1864 until his death.

Hanslick had traditional ideas about music. He strongly believed in absolute music, which means music that is enjoyed just for its sounds and structure, without trying to tell a story or describe something. He was against programmatic music, which does try to tell a story. Because of this, he supported composers like Robert Schumann and Johannes Brahms in a big musical debate called the "War of the Romantics". He often criticized the music of composers like Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner. His most famous work is a book from 1854 called Vom Musikalisch-Schönen (On the Musically Beautiful). This book was very important for understanding the aesthetics of music (the study of beauty in music) and showed many of his ideas about art and music.

Contents

Biography

Eduard Hanslick was born in Prague, which was then part of the Austrian Empire. His father, Joseph Adolph Hanslik, was a bibliographer (someone who studies books) and a music teacher. His mother was one of his father's piano students.

When he was 18, Hanslick began studying music with Václav Tomášek, a famous musician in Prague. He also studied law at Charles University and earned a law degree. However, his love for music led him to start writing music reviews for small newspapers. Later, he wrote for the Wiener Musik-Zeitung and eventually became the music critic for the Neue Freie Presse, where he worked until he retired.

In 1845, while still a student, he met Richard Wagner. Wagner noticed Hanslick's excitement for music and invited him to hear his opera Tannhäuser in Dresden. There, Hanslick also met Robert Schumann.

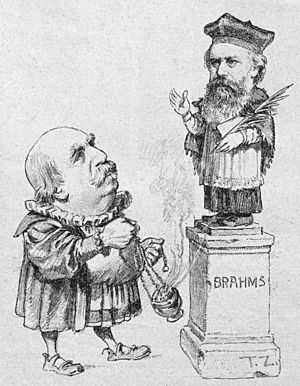

In 1854, Hanslick published his important book On the Beautiful in Music. Around this time, his interest in Wagner's music began to fade. He wrote a negative review of Wagner's opera Lohengrin when it was first performed in Vienna. From then on, Hanslick preferred music that followed the traditions of composers like Mozart, Beethoven, and Schumann. He especially admired the music of Johannes Brahms, who even dedicated a set of waltzes (his Opus 39) to Hanslick.

In 1869, Richard Wagner wrote an essay where he criticized Hanslick, suggesting Hanslick's style of criticism was "anti-German." Some people believe that Wagner created the character Beckmesser, a critical and complaining character in his opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, to make fun of Hanslick. (Beckmesser's original name was even going to be Veit Hanslich).

Hanslick started as an unpaid lecturer at the University of Vienna. In 1870, he became a full professor of music history and aesthetics. He later received an honorary doctorate degree. Hanslick often served on judging panels for music competitions and held positions in the Austrian Ministry of Culture. He retired after writing his memoirs but continued to write articles about important new music performances until his death in 1904 in Baden.

Hanslick's Ideas About Music

Eduard Hanslick had traditional musical tastes. In his memoirs, he said that for him, music history truly began with Mozart and reached its peak with Beethoven, Schumann, and Brahms. He is best known today for strongly supporting Brahms against the ideas of Wagner. This disagreement is often called the "War of the Romantics" in 19th-century music history.

Hanslick was a close friend of Brahms starting in 1862. He often heard Brahms's new music before it was published, and he might have influenced Brahms's compositions. Hanslick believed that Wagner's focus on drama and "word painting" (using music to describe words) went against the true nature of music. He thought music should express itself only through its form and sounds, not through outside ideas or stories.

His main ideas about music criticism are explained in his 1854 book, Vom Musikalisch-Schönen (On the Beautiful in Music). This book started as a criticism of Wagner's ideas and became a very important text, reprinted many times and translated into several languages. Hanslick also strongly criticized composers like Anton Bruckner and Hugo Wolf. He famously said that Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto put the audience "through hell" with music that "stinks to the ear." He also wasn't very impressed by Tchaikovsky's Sixth Symphony.

Hanslick is seen as one of the first widely influential music critics. He believed that the meaning of music comes from its form and structure. This is why he became one of Brahms's biggest supporters and often compared him to Wagner. Because of this, people sometimes mistakenly think Brahms was against Wagner, but they actually admired each other's work.

On the Musically Beautiful (Vom Musikalisch-Schönen)

First published in 1854, Hanslick's book On the Musically Beautiful is considered a very important text in modern musical aesthetics. It helped to define ideas about music being independent and having its own inner logic. Hanslick was the first professor to teach music history and aesthetics at a university. While his book laid the groundwork for analyzing music's form, Hanslick himself didn't actually do much formal analysis.

Chapter 1: Feelings and Music

This chapter criticizes the common idea that music's beauty comes from the feelings it creates. Hanslick called this the "aesthetics of feeling." He listed many authors who believed music was mainly about expressing emotions. He ended his list with Richard Wagner, making it clear that Wagner was his main target. Wagner had recently written an essay, Opera and Drama, explaining how his music expressed feelings through poetry.

Hanslick disagreed, saying that music is beautiful on its own, even if it doesn't make anyone feel a specific emotion. He wrote that "The beautiful is and remains beautiful though it arouse no emotion whatever."

Chapter 2: Music Doesn't Show Feelings

Hanslick argued that feelings are not actually in the music itself (they are objective), but depend on what the listener thinks (they are subjective). So, feelings cannot be the basis for understanding music's beauty. He agreed that music might "awaken feelings" in a listener, but he insisted it cannot "represent" or show them directly.

Chapter 3: What is Beautiful in Music?

Hanslick stated, "The essence of music is sound and motion." He suggested that the true basis for music's beauty lies in its "sonically moving forms." He believed these forms grow from a musical theme that a composer freely creates.

He explained that a composition starts with a definite theme, not with a desire to describe an emotion. This theme appears in the composer's mind and then grows and develops. The main theme is like a center, and other musical ideas branch out from it, always connected. The beauty of a simple theme appeals directly to us, like a beautiful pattern or a flower. It is pleasing just for itself.

Chapter 4: How We Listen to Music

Hanslick looked at the composer, the musical work itself, and the listener. He argued that composing music is an intellectual process, not just an emotional one. He believed that it is "the purely musical features of a composition" that create feelings in a listener, not the composer's actual feelings. He also discussed how our hearing works and its limits. He concluded that theories based on feelings are not scientific because they don't truly understand the connection between music and emotion.

Chapter 5: Two Ways of Listening

Hanslick described two ways of listening to music: active ("aesthetic") and passive ("pathological"). An active listener tries to understand how the composer built the music. A passive listener just hears the sounds.

He wrote that the most important part of enjoying music is the "intellectual satisfaction" a listener gets from following and guessing the composer's ideas. This happens quickly and without us even realizing it. Only music that encourages this kind of thoughtful listening can provide true artistic enjoyment.

Chapter 6: Music and Nature

Hanslick believed that melody is the "life-blood" of a musical piece, and both melody and harmony are human creations. However, he thought that rhythm, especially a simple two-beat rhythm, can be found in nature. He said it's the only musical element nature has, and it's the first one we notice. But he still believed music is a product of the human mind, not something found in nature. Even if a composer imitates bird calls, Hanslick argued that it's not truly music because its purpose is to describe something outside of music, not to be musical itself.

Chapter 7: Form and Content in Music

Hanslick concluded that the "idea" in music can only be purely musical. He wrote, "Music consists of successions and forms of sound, and these alone constitute the subject." He believed that the value of a piece of music depends on how well the main idea (like the theme) relates to the entire work.

He explained that you can only understand the "subject" of a musical theme by listening to it. The subject of a composition is something musical itself, like the specific sounds in a piece. Since a composition must follow the rules of beauty, it cannot be random. Instead, it must develop clearly and organically, like buds growing into flowers.

Works (German editions)

- Eduard Hanslick, "Vom Musikalisch-Schönen". Leipzig 1854 (online version)

- Eduard Hanslick, "Geschichte des Konzertwesens in Wien", 2 vol. Vienna 1869–70

- Eduard Hanslick, "Die moderne Oper", 9 vol. Berlin 1875–1900

- Eduard Hanslick, "Aus meinem Leben", 2 vol. Berlin 1894

- Eduard Hanslick, "Suite. Aufsätze über Musik und Musiker". Vienna 1884

Compositions

- Milostná píseň pod Vyšehradem (Love song beneath Vyšehrad) for violin and piano, op.9

See also

In Spanish: Eduard Hanslick para niños

In Spanish: Eduard Hanslick para niños

- Aesthetics of music