Symphony No. 5 (Beethoven) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Symphony in C minor |

|

|---|---|

| No. 5 | |

| by Ludwig van Beethoven | |

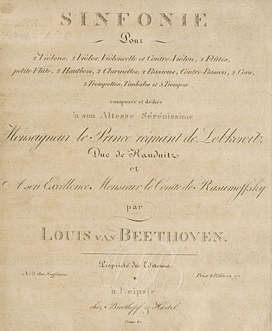

Cover of the symphony, with the dedication to Prince J. F. M. Lobkowitz and Count Rasumovsky

|

|

| Key | C minor |

| Opus | 67 |

| Form | Symphony |

| Composed | 1804–1808 |

| Dedication |

|

| Duration | About 30–40 minutes |

| Movements | Four |

| Scoring | Symphony orchestra |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 22 December 1808 |

| Location | Theater an der Wien, Vienna |

| Conductor | Ludwig van Beethoven |

The Symphony No. 5 in C minor, also known as the Fate Symphony, is a famous piece of music by Ludwig van Beethoven. He wrote it between 1804 and 1808. It is one of the most recognized and played symphonies in classical music. Many people consider it a very important work in Western music.

The symphony first played in Vienna in 1808. It quickly became very popular. A writer named E. T. A. Hoffmann called it "one of the most important works of the time." Like most symphonies from Beethoven's era, it has four main parts, called movements.

It starts with a very famous four-note tune: "short-short-short-long." People often say this sounds like "fate knocking at the door." This special tune is called the Schicksals-Motiv (fate motif).

This symphony, especially its opening tune, is famous worldwide. You can hear the tune in many places, from disco songs to rock and roll covers, and in movies and TV shows.

Beethoven gave some of his symphonies special names, like his "Eroica" (heroic) and "Pastorale" (rural). The Fifth Symphony also got a nickname, "Fate Symphony," but Beethoven himself didn't choose it.

Contents

About the Symphony No. 5

How it was Created

Beethoven worked on his Fifth Symphony for a long time. He started writing down musical ideas, called "sketches," in 1804. This was right after he finished his Third Symphony.

He often paused his work on the Fifth Symphony to write other pieces. These included his opera Fidelio, the Appassionata piano sonata, and several other symphonies and concertos. He finished the Fifth Symphony between 1807 and 1808. He was also working on his Sixth Symphony at the same time. Both symphonies were first played at the same concert!

Beethoven was in his mid-thirties during this time. He was dealing with increasing deafness, which was very difficult for a musician. The world around him was also busy with the Napoleonic Wars. There was political unrest in Austria, and Napoleon's soldiers even occupied Vienna in 1805. Beethoven wrote this symphony in his home at the Pasqualati House in Vienna.

Its First Performance

The Fifth Symphony had its very first performance on December 22, 1808. It was part of a huge concert in Vienna at the Theater an der Wien. Beethoven himself conducted the orchestra. The concert was incredibly long, lasting over four hours!

All the music played that night was new work by Beethoven. Interestingly, the two symphonies were played in reverse order. The Sixth Symphony was heard first, and the Fifth Symphony came in the second half.

Here is what was played at that famous concert:

- The Sixth Symphony

- An aria (a song for a solo singer) called Ah! perfido

- The Gloria part of the Mass in C major

- The Fourth Piano Concerto (Beethoven played the piano himself!)

- (A break)

- The Fifth Symphony

- The Sanctus and Benedictus parts of the C major Mass

- A solo piano improvisation by Beethoven

- The Choral Fantasy

Beethoven dedicated his Fifth Symphony to two important people who supported him. They were Prince Joseph Franz von Lobkowitz and Count Razumovsky. The dedication was printed in the first copies of the music in April 1809.

What Instruments are Used?

The symphony is written for a large orchestra. It uses many different instruments to create its powerful sound.

- Woodwind instruments

- 1 piccolo (only in the fourth movement)

- 2 flutes

- 2 oboes

- 2 clarinets (in B♭ for the first three movements, and C for the fourth)

- 2 bassoons

- 1 contrabassoon (only in the fourth movement)

- Brass instruments

- 2 horns (in E♭ for the first and third movements, and C for the second and fourth)

- 2 trumpets in C

- 3 trombones (alto, tenor, and bass, only in the fourth movement)

- Percussion instruments

- timpani (kettledrums)

- String instruments

- First violins

- Second violins

- violas

- cellos

- double basses

The Four Parts of the Symphony

A full performance of the symphony usually takes about 30 to 40 minutes. It has four distinct parts, or movements:

- Allegro con brio (Fast and lively) – This part is in C minor.

- Andante con moto (Walking pace, with motion) – This part is in A♭ major.

- Scherzo: Allegro (Playful and fast) – This part is in C minor.

- Allegro – Presto (Fast, then very fast) – This part is in C major.

Part 1: Fast and Energetic (Allegro con brio)

The first movement starts with the famous four-note tune. This is one of the most well-known musical ideas in all of Western music. Musicians sometimes debate how to play these first few notes. Some play them strictly fast, while others play them slower and more grandly.

This movement follows a traditional sonata form. This was a common structure for composers like Haydn and Mozart. In sonata form, main musical ideas are introduced, then developed and changed, and finally return in a grand way.

The movement begins with two powerful, loud phrases of the famous motif. These grab the listener's attention right away. Beethoven then builds on this theme using musical echoes and patterns. These short musical ideas seem to tumble over each other, creating a flowing melody.

After a short, loud bridge played by the horns, a second theme appears. This theme is softer and more singing. It is in E♭ major, a related key. The four-note motif can still be heard in the background, played by the strings. The movement ends with a large closing section called a coda.

This first part usually lasts about 7 to 8 minutes.

Part 2: Slow and Moving (Andante con moto)

The second movement is in A♭ major. It is a gentle and flowing piece. It uses a "double variation" form. This means two main tunes are presented and then changed in different ways, one after the other. After these variations, there is a long closing section.

The movement starts with its first tune played by the violas and cellos together. The double basses provide a soft accompaniment. Soon, a second tune appears. Clarinets, bassoons, and violins play harmonies for this tune. Violas play a quick, flowing pattern of notes.

The first tune returns with some changes. Then, a third tune is introduced. This one features very fast notes in the violas and cellos. Flutes, oboes, and bassoons play a contrasting melody above them. After a short break, the whole orchestra plays loudly. This leads to several crescendos (getting louder) and a coda to finish the movement.

This second part usually lasts about 8 to 11 minutes.

Part 3: Playful and Lively (Scherzo: Allegro)

The third movement is a scherzo, which means "joke" in Italian. It's usually a fast and playful dance. Beethoven often used a scherzo instead of the older "minuet" for the third movement of his symphonies.

This movement returns to the key of C minor. It begins with a theme played by the cellos and double basses.

Wind instruments then play a different, contrasting tune. This pattern of themes repeats. Next, the horns loudly announce the main theme of the movement. The music then continues to develop.

There's a middle section called the "trio," which is in C major. It has a complex, interwoven musical texture. When the scherzo theme returns, the strings play it very softly and pizzicato (plucking the strings instead of bowing).

This movement is also famous for how it smoothly leads into the fourth movement. Many consider this one of the greatest musical transitions ever written.

This third part usually lasts about 4 to 8 minutes.

Part 4: Triumphant Finale (Allegro)

The fourth movement begins without any pause after the third movement. The music bursts into C major. This was an unusual choice for Beethoven. Symphonies that start in C minor usually end in that same key. Beethoven once said, "Joy follows sorrow, sunshine—rain." This shows his idea of moving from a dark, stormy mood to a bright, victorious one.

This exciting finale uses a special version of sonata form. Near the end of the development section, the music stops loudly. After a short pause, a quiet version of the "horn theme" from the scherzo movement returns. Then, the main themes of the finale come back, building up with a crescendo.

Beethoven's finale includes a very long closing section, or coda. In this part, the main tunes are played faster and faster. The tempo increases to presto, meaning "very fast." The symphony ends with 29 powerful C major chords, played very loudly. Music expert Charles Rosen said this long, loud ending was needed to balance the huge energy of the entire symphony.

This fourth part usually lasts about 8 to 11 minutes.

Interesting Facts and Stories

The "Fate" Motif

The famous opening four-note tune of the symphony has a special meaning for some people. They say it represents Fate knocking at the door. This idea came from Anton Schindler, who was Beethoven's secretary. Many years after Beethoven died, Schindler wrote that Beethoven himself said this about the music.

However, many experts don't fully trust Schindler's stories. Some believe he made up or changed parts of Beethoven's history. He often presented a very dramatic picture of the composer.

There's another story about the same motif. Carl Czerny, who was Beethoven's student, claimed that Beethoven got the idea from a yellowhammer bird's song. He heard it while walking in a park in Vienna. Music writer Antony Hopkins noted that people usually prefer the more dramatic "Fate knocking" story. But he also said Czerny's bird story seems too unusual to be invented.

In a TV show in 1954, Leonard Bernstein compared the Fate Motif to a common musical ending. He said Beethoven turned this ending into a repeating motif throughout the symphony. This created a very different and dramatic effect.

Many experts are careful about these interpretations. Some say the "Fate knocking" idea was actually from Beethoven's student, Ferdinand Ries. They say Beethoven reacted sarcastically when Ries told him this idea. Another expert, Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner, suggested Beethoven might have said anything to get rid of annoying questions. This makes both stories a bit uncertain.

Why C Minor?

The key of the Fifth Symphony is C minor. This key was very special for Beethoven. It often appeared in his "stormy, heroic" pieces. Beethoven wrote several other works in C minor that have a similar powerful character.

Pianist and writer Charles Rosen explained that C minor became a symbol of Beethoven's artistic personality. He said that in C minor, Beethoven shows himself as a hero. It might not be his most subtle music, but it is his most outgoing. In these pieces, he seems unwilling to compromise.

A Repeating Musical Idea?

Many people believe that the opening four-note rhythm (short-short-short-long) is repeated throughout the entire symphony. They think it helps to connect all the parts. Some say it appears in almost every measure of the first movement. They also believe it shows up in the other movements, even with some changes.

However, some experts don't think these resemblances are intentional. Music writer Antony Hopkins said that the rhythms in the scherzo and the first movement are too different to be confused. Donald Tovey also disagreed. He said that if you look closely, this rhythm appears in many other works by Beethoven. It was a common musical pattern of the time.

So, whether Beethoven deliberately used this rhythm to connect the symphony is still a topic of discussion among musicians.

New Sounds in the Orchestra

The last movement of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony was special for using certain instruments for the first time in a symphony. These included the piccolo and the contrabassoon. While this was Beethoven's first time using the trombone in a symphony, another composer, Joachim Nicolas Eggert, had already used trombones in his Symphony No. 3 in 1807.

How Others Used the Symphony

Franz Liszt, a famous composer and pianist, created a version of the Fifth Symphony for solo piano. It is part of his collection called Symphonies de Beethoven, S. 464.

See also

In Spanish: Sinfonía n.º 5 (Beethoven) para niños

In Spanish: Sinfonía n.º 5 (Beethoven) para niños

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |