Western canon facts for kids

The Western canon is a collection of important books, music, art, and ideas that are highly valued in Western culture. These works are considered "classics" because they have stood the test of time and are still important today. While many of these works come from the West, they are also appreciated all over the world.

Think of it as a special list of works that have shaped Western thinking, from ancient Greek philosophers like Socrates to modern writers like James Joyce. The word 'canon' comes from an old Greek word meaning "measuring rod" or "standard." The Bible, which comes from ancient Jewish culture in Western Asia, has also played a huge role in shaping Western culture and has inspired many great works of art and literature.

Recently, people have been talking about making the canon bigger to include more works by women and people from different racial backgrounds. The canons for music and art have already grown to include works from the Middle Ages and later centuries that were once overlooked. Even newer forms of art, like cinema, are starting to find their place. Also, there's a growing interest in major artworks from cultures in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America.

Great Books and Classic Works

A classic book is a book, or any other work of art, that is seen as an excellent example or is very important. The idea of "ranking" cultural works started with the ancient Greeks. Early Christian leaders also used the word canon to list the most important texts of the New Testament. This helped preserve these texts because materials like vellum and papyrus were expensive, and copying books was hard work. Being part of a "canon" meant a book was saved as a way to keep knowledge about a civilization.

Today, the Western canon helps define the best of Western culture. In ancient times, scholars at the Library of Alexandria used a Greek term meaning "the admitted" or "the included" to identify writers in their canon. While often linked to the West, this idea can apply to literature, music, and art from any tradition, like the Chinese classics or the Vedas.

Many authors, from Mark Twain to Italo Calvino, have wondered what makes a book a "classic." Questions like "Why Read the Classics?" and "What Is a Classic?" have been explored by thinkers such as T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound.

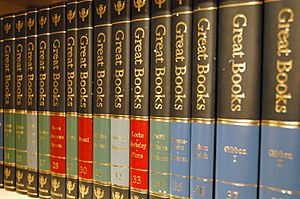

The terms "classic book" and "Western canon" are closely related but not exactly the same. A "canon" is a list of books considered "essential." These lists can be published as collections (like Great Books of the Western World or Penguin Classics) or be official reading lists for universities. For example, Harold Bloom's book The Western Canon lists major Western writers such as Dante, William Shakespeare, and James Joyce.

University Programs for Great Books

Many universities and colleges offer a Great Books Program. This idea started in the United States in the 1920s with Professor John Erskine of Columbia University. He wanted to improve higher education by bringing back the Western liberal arts tradition, which focuses on learning across many different subjects.

Academics like Robert Maynard Hutchins and Mortimer J. Adler believed that focusing too much on narrow specializations in American colleges was harming education. They felt students weren't being exposed to the important works of Western civilization.

A key part of these programs is deeply studying original texts, known as the Great Books. The courses often follow a list of texts considered essential for a student's education, such as Plato's Republic or Dante's Divine Comedy. These programs usually focus only on Western culture. Since the Great Books cover many topics, these programs use an interdisciplinary approach, meaning they connect different subjects. Great Books programs often include discussion groups and lectures, with small class sizes. Students usually get a lot of attention from their professors, helping to create a strong learning community.

More than 100 colleges and universities, mostly in the United States, offer some form of a Great Books Program.

For much of the 20th century, the Modern Library provided a popular list of Western canon books. This list included over 300 items by the 1950s, from authors like Aristotle to Albert Camus, and it kept growing. When the idea of the Western canon faced strong criticism in the 1990s, the Modern Library created new lists of "100 Best Novels" and "100 Best Nonfiction" compiled by famous writers.

Discussions About the Canon

Some thinkers believe that universal truths exist and have defended the canon against ideas that deny these truths. Yale University Professor Harold Bloom strongly supported the canon in his 1994 book The Western Canon: The Books and School of the Ages. The canon remains an important idea in many schools and universities.

Allan Bloom (no relation to Harold Bloom), in his influential book The Closing of the American Mind (1987), argued that ignoring the great classics that shaped Western culture leads to moral decline. He said, "But one thing is certain: wherever the Great Books make up a central part of the curriculum, the students are excited and satisfied." Many intellectuals agreed with his idea that the classics contain universal truths and timeless values that were being overlooked.

Classicist Bernard Knox discussed this topic in his 1992 Jefferson Lecture. He used the title "The Oldest Dead White European Males" to defend the ongoing importance of classical culture in modern society.

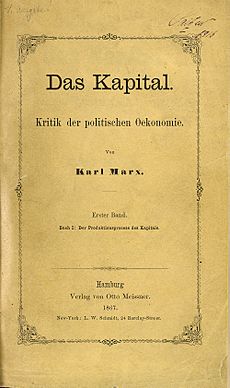

Supporters of the canon argue that those who criticize it do so for political reasons, and that these criticisms are mistaken. John Searle, a Professor of Philosophy at the University of California, Berkeley, pointed out that earlier generations found the critical tradition, from Socrates to Karl Marx, to be freeing. He said that by teaching a critical attitude, the "canon" helped students question traditional ideas. Ironically, this same tradition is now sometimes seen as oppressive.

One main question about a canon of literature is who decides which works are worth reading.

Charles Altieri of the University of California, Berkeley, says that canons are "an institutional form for exposing people to a range of idealized attitudes." This means that works might be removed from the canon over time to reflect society's changing ideas. American historian Todd M. Compton believes that canons are always shared by a community. He argues that there are many different canons, like for a literature class, and no single, absolute canon of literature. He sees Bloom's "Western Canon" as a personal list.

The process of defining the canon's boundaries is always ongoing. Philosopher John Searle said, "In my experience there never was, in fact, a fixed 'canon'; there was rather a certain set of tentative judgments about what had importance and quality. Such judgments are always subject to revision, and in fact they were constantly being revised."

One notable effort to create an authoritative canon for English literature was the Great Books of the Western World program. This program, developed in the mid-20th century, grew out of the curriculum at the University of Chicago. University president Robert Maynard Hutchins and Mortimer J. Adler created reading lists, books, and ways for reading clubs to engage with the public. Earlier, in 1909, Harvard University president Charles W. Eliot created the Harvard Classics, a 51-volume collection of classic works from world literature. Eliot shared the view of Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle: "The true University of these days is a Collection of Books."

Expanding the Literary Canon in the 20th Century

In the 20th century, there was a big reevaluation of the literary canon. This included looking at women's writing, post-colonial literature (writing from countries that were once colonies), gay and lesbian literature, writing by people of color, and works by historically marginalized groups. This led to a huge expansion of what is considered "literature." Genres not previously seen as "literary," such as children's writing, journals, letters, and travel writing, are now studied by scholars.

The Western literary canon has also grown to include literature from Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and South America. Writers from these regions have won Nobel Prizes since the late 1960s. They have also been nominated for and won the Booker Prize in recent years.

Women and the Literary Canon

Some argue that the Western canon has kept itself going by leaving out and marginalizing women, while focusing on the works of European men. When women's work is included, it might not be recognized for its true importance. Instead, a work's "greatness" is often judged by factors that tend to exclude women, even though this is presented as an intellectual approach.

The feminist movement led to both feminist fiction and non-fiction. It also sparked new interest in women's writing. This movement encouraged a reevaluation of women's historical and academic contributions. This was a response to the belief that women's lives and contributions had been underrepresented in scholarly studies.

However, in Britain and America, women achieved great literary success from the late 18th century. Many major 19th-century British novelists were women, including Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, Elizabeth Gaskell, and George Eliot. There were also three major female poets: Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Christina Rossetti, and Emily Dickinson. In the 20th century, many important female writers emerged, such as Virginia Woolf and Simone de Beauvoir.

Much of the early feminist literary scholarship focused on finding and bringing back texts written by women. Virago Press began publishing its large list of 19th and early 20th-century novels in 1975. It became one of the first commercial publishers to join this effort to rediscover women's works.

African and African-American Authors

In the 20th century, the Western literary canon began to include African writers. This meant not only African-American writers but also writers from the wider African diaspora in Britain, France, Latin America, and Africa. This change largely happened alongside the shift in social and political views during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

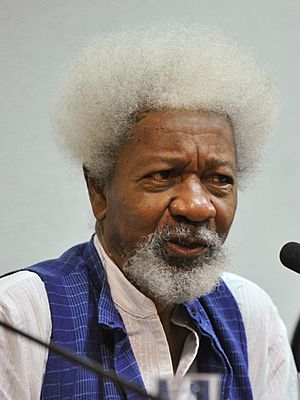

The first global recognition for an African American writer came in 1950 when Gwendolyn Brooks won a Pulitzer Prize for Literature. Chinua Achebe's novel Things Fall Apart helped bring attention to African literature. Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka was the first African to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986. American writer Toni Morrison was the first African-American woman to win it in 1993.

Some early African-American writers wanted to challenge widespread racial prejudice. They aimed to prove they were just as good as European American authors. As Henry Louis Gates, Jr., said, "it is fair to describe the subtext of the history of black letters as this urge to refute the claim that because blacks had no written traditions they were bearers of an inferior culture."

African-American writers also tried to change the literary and power traditions of the United States. Some scholars say that writing has traditionally been seen as "something defined by the dominant culture as a white male activity." This means that, in American society, being accepted in literature has often been linked to the very power structures that caused racial discrimination. By using and including the oral traditions and folk life of the African diaspora, African-American literature broke "the mystique of connection between literary authority and patriarchal power." By creating their own literature, African Americans could establish their own literary traditions without needing approval from European thinkers. This idea of African-American literature as a tool for political and cultural freedom has been expressed for decades, most famously by W. E. B. Du Bois.

Asia and North Africa

Since the 1960s, the Western literary canon has expanded to include writers from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. This is shown by the Nobel Prizes awarded in literature.

Yasunari Kawabata (1899–1972) was a Japanese novelist and short story writer. His simple, poetic, and subtle prose won him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968. He was the first Japanese author to receive this award. His works are still widely read and enjoyed around the world.

Naguib Mahfouz (1911–2006) was an Egyptian writer who won the 1988 Nobel Prize in Literature. He is considered one of the first modern writers of Arabic literature to explore ideas like existentialism. He published 34 novels, over 350 short stories, and many movie scripts and plays during his 70-year career. Many of his works have been made into Egyptian and foreign films.

Kenzaburō Ōe (born 1935) is a Japanese writer and a major figure in modern Japanese literature. His novels, short stories, and essays are influenced by French and American literature. They deal with political, social, and philosophical issues, including nuclear weapons, nuclear power, and existentialism. Ōe won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1994 for creating "an imagined world, where life and myth combine to form a surprising picture of the human situation today."

Guan Moye (born 1955), known as "Mo Yan," is a Chinese novelist and short story writer. TIME magazine called him "one of the most famous, often-banned and widely pirated of all Chinese writers." He is best known to Western readers for his 1987 novel Red Sorghum Clan, which was adapted into the film Red Sorghum. In 2012, Mo won the Nobel Prize in Literature for his writing, which "with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary."

Orhan Pamuk (born 1952) is a Turkish novelist, screenwriter, and professor. He won the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature. He is one of Turkey's most famous novelists, and his work has sold over thirteen million books in sixty-three languages, making him the country's best-selling writer. Pamuk's novels include My Name Is Red and Snow. He teaches writing and comparative literature at Columbia University. Born in Istanbul, Pamuk is the first Turkish Nobel laureate and has received many other literary awards.

Latin America

Octavio Paz (1914–1998) was a Mexican poet and diplomat. He won the 1990 Nobel Prize in Literature for his body of work.

Gabriel García Márquez (1927–2014) was a Colombian novelist, short-story writer, screenwriter, and journalist. He is considered one of the most important authors of the 20th century and one of the best in the Spanish language. He won the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature.

García Márquez started as a journalist and wrote many acclaimed non-fiction works and short stories. However, he is best known for his novels, such as One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) and Love in the Time of Cholera (1985). His works have received great praise and commercial success, especially for popularizing a literary style called magic realism. This style uses magical elements and events in otherwise ordinary and realistic situations. Some of his works are set in a fictional village called Macondo, and most of them explore the theme of solitude. When he died in April 2014, the President of Colombia, Juan Manuel Santos, called him "the greatest Colombian who ever lived."

Mario Vargas Llosa (born 1936) is a Peruvian writer, politician, journalist, essayist, and college professor. He won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature. Vargas Llosa is one of Latin America's most important novelists and essayists, and a leading writer of his generation. Some critics believe he has had a greater international impact and audience than any other writer of the Latin American Boom. When announcing his Nobel Prize, the Swedish Academy said it was given to him "for his mapping of structures of power and his sharp images of the individual's resistance, revolt, and defeat."

Important Philosophers

Many philosophers today agree that Greek philosophy has greatly influenced Western culture since it began. Alfred North Whitehead once said: "The safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato." Clear connections can be traced from ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophers to Early Islamic philosophy, the European Renaissance, and the Age of Enlightenment.

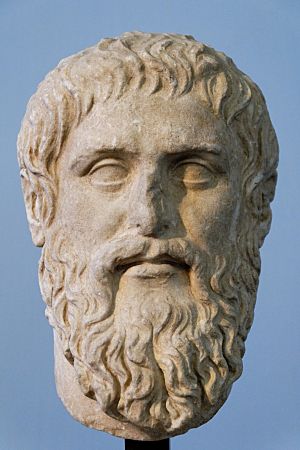

Plato was a philosopher in Classical Greece and founded the Academy in Athens. He is widely seen as the most important figure in the development of philosophy, especially the Western tradition.

Aristotle was an ancient Greek philosopher. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, biology, zoology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, and government. His work forms the first complete system of Western philosophy. Aristotle's ideas about physical science had a deep impact on medieval learning. Their influence lasted from Late Antiquity into the Renaissance, and his views were not fully replaced until the Enlightenment with theories like classical mechanics. In metaphysics, Aristotelianism strongly influenced Jewish-Islamic philosophical and theological thought during the Middle Ages. It continues to influence Christian theology, especially the Neoplatonism of the Early Church and the scholastic tradition of the Roman Catholic Church. Aristotle was well known among medieval Muslim thinkers and was called "The First Teacher." His ethics, always influential, gained new interest with the modern rise of virtue ethics.

The vast amount of Christian philosophy is usually represented by Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas in reading lists. The academic canon of early modern philosophy generally includes Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, Hume, and Kant.

Philosophers of the Renaissance

Important philosophers from the Renaissance include Niccolò Machiavelli, Michel de Montaigne, Pico della Mirandola, Nicholas of Cusa, and Giordano Bruno.

Philosophers of the 17th Century

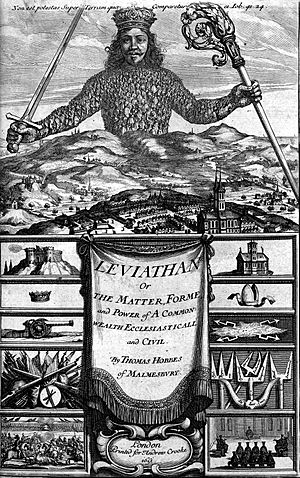

The 17th century was very important for philosophy. Key figures were Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, Blaise Pascal, Baruch Spinoza, John Locke, and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz.

Philosophers of the 18th Century

Major philosophers of the 18th century include George Berkeley, Montesquieu, Voltaire, David Hume, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot, Immanuel Kant, Edmund Burke, and Jeremy Bentham.

Philosophers of the 19th Century

Important 19th-century philosophers include Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Auguste Comte, Søren Kierkegaard, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Friedrich Nietzsche.

Philosophers of the 20th Century

Major figures in the 20th century include Henri Bergson, Edmund Husserl, Bertrand Russell, Martin Heidegger, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Simone Weil, Michel Foucault, Pierre Bourdieu, Jacques Derrida, and Jürgen Habermas. During this time, a distinction between analytic and continental approaches to philosophy became noticeable.

Music Classics

Classical music forms the main part of the music canon and has largely remained the same. It includes a huge number of works starting from the 17th century, played on acoustic musical instruments common in Europe at that time.

The term "classical music" didn't appear until the early 19th century. It was used to specifically highlight the period from Johann Sebastian Bach to Ludwig van Beethoven as a golden age. Besides Bach and Beethoven, other major composers from this time were George Frideric Handel, Joseph Haydn, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The earliest mention of "classical music" in the Oxford English Dictionary is from around 1836.

In classical music, a "canon" developed during the 19th century. It focused on what were considered the most important works written since 1600, with a strong emphasis on the later part of this period, called the Classical period, which generally began around 1750. After Beethoven, major 19th-century composers include Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Frédéric Chopin, Richard Wagner, Johannes Brahms, and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

In the 2000s, the usual concert programs for professional orchestras, chamber music groups, and choirs tend to feature works by a relatively small number of mostly 18th- and 19th-century male composers. Many works considered part of the musical canon are from the most "serious" genres, such as the symphony, concerto, string quartet, and opera. Folk music had already influenced art music melodies. From the late 19th century, with increasing nationalism, folk music began to influence composers in more formal ways before being accepted into the canon itself.

Since the early 20th century, non-Western music has started to influence Western composers. For example, direct tributes to Javanese gamelan music can be found in works by Claude Debussy, Béla Bartók, and Philip Glass. Debussy was very interested in non-Western music and its ways of composing. He was especially drawn to the Javanese gamelan, which he first heard at the 1889 Paris Exposition. He didn't directly copy his non-Western influences but allowed this aesthetic to generally shape his own music. For instance, he often used quiet, unresolved dissonances with the damper pedal to imitate the "shimmering" effect of a gamelan ensemble. American composer Philip Glass was influenced not only by the French composition teacher Nadia Boulanger but also by Indian musicians Ravi Shankar and Alla Rakha. His unique style came from his work with Shankar and Rakha and their understanding of rhythm in Indian music as being entirely additive.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the canon expanded to include Early music from the pre-classical period and Baroque music by composers other than Bach and George Frideric Handel. This includes composers like Antonio Vivaldi, Claudio Monteverdi, Henry Purcell, and Georg Philipp Telemann. Even earlier composers, such as Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and William Byrd, have received more attention in the last hundred years.

The absence of women composers from the classical canon became a major topic in music studies in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Even though many women composers wrote music during the common practice period and beyond, their works are still very rarely performed in concerts, taught in music history classes, or included in music collections. Musicologist Marcia J Citron has studied "the practices and attitudes that have led to the exclusion of women composers from the received 'canon' of performed musical works." Since around 1980, the music of Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), a German Benedictine abbess, and Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho (born 1952) has begun to enter the canon. Saariaho's opera L'amour de loin has been performed in major opera houses around the world.

The classical music canon rarely includes musical instruments that are not acoustic and of Western origin. It has largely stayed separate from the widespread use of electric, electronic, and digital instruments common in today's popular music.

Visual Arts

The foundation of traditional Western art history consists of artworks created for wealthy patrons for private or public enjoyment. Much of this was religious art, mostly Roman Catholic art. The classical art of Greece and Rome has been the source of the Western tradition since the Renaissance.

Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574) is considered the creator of the artistic canon and many of its ideas. His book Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects only covers artists working in Italy, with a strong preference for Florentine artists. This book has had a lasting impact. Northern European art has arguably never quite reached the same level of prestige as Italian art. Vasari's idea of Giotto as the founder of "modern" painting has largely stuck. In painting, the general term Old master refers to painters up to the time of Goya.

This "canon" remains important, as seen in the selections in art history textbooks and the prices artworks fetch in the art trade. However, what is valued has changed a lot over time. In the 19th century, the Baroque style fell out of favor but was revived around the 1920s. By then, the art of the 18th and 19th centuries was largely ignored. The High Renaissance, which Vasari considered the greatest period, has always kept its prestige, including works by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. But the period that followed, Mannerism, has gone in and out of favor.

In the 19th century, the start of academic art history, led by German universities, led to a much better understanding and appreciation of medieval art. It also brought a more detailed understanding of classical art, including the realization that many treasured sculptures were late Roman copies rather than original Greek works. The European art tradition expanded to include Byzantine art and new discoveries from archaeology, such as Etruscan art, Celtic art, and Upper Paleolithic art.

Since the 20th century, there has been an effort to redefine the field to include more art made by women. There's also a greater appreciation for everyday creativity, especially in printed media, and an expansion to include works in the Western tradition produced outside Europe. At the same time, there has been much greater appreciation for non-Western traditions, including their place alongside Western art in broader global traditions. The decorative arts have traditionally had a much lower critical status than fine art, even though collectors often value them highly. They still tend to receive little attention in university studies or popular media.

Women and Art

English artist and sculptor Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975), whose work is a great example of Modernism and modern sculpture, is one of the few female artists to become internationally famous. In 2016, the art of American modernist Georgia O'Keeffe was shown at the Tate Modern in London, then moved to Vienna, Austria, and later to the Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada.

Historical Exclusion of Women in Art

Women faced discrimination in getting the training needed to become artists in the mainstream Western traditions. Also, since the Renaissance, the nude (often female) has held a special place as a subject. In her 1971 essay, "Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?", Linda Nochlin analyzed what she saw as the built-in privilege in the mostly male Western art world. She argued that women's outsider status gave them a unique perspective to criticize not only women's position in art but also the field's basic assumptions about gender and ability. Nochlin's essay argues that both formal and social education limited artistic development to men, preventing women (with rare exceptions) from improving their talents and entering the art world.

In the 1970s, feminist art criticism continued this critique of the unfair sexism in art history, art museums, and galleries. It questioned which types of art were considered worthy of being in a museum. Artist Judy Chicago explained this view:

It is crucial to understand that one of the ways in which the importance of male experience is conveyed is through the art objects that are exhibited and preserved in our museums. Whereas men experience presence in our art institutions, women experience primarily absence, except in images that do not necessarily reflect women's own sense of themselves.

See also

In Spanish: Canon occidental para niños

In Spanish: Canon occidental para niños

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |