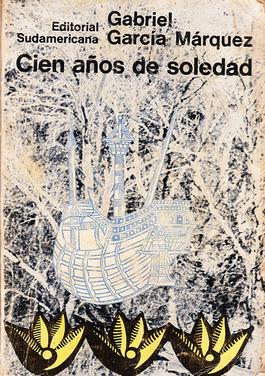

One Hundred Years of Solitude facts for kids

First edition

|

|

| Author | Gabriel García Márquez |

|---|---|

| Original title | Cien años de soledad |

| Translator | Gregory Rabassa |

| Country | Argentina |

| Language | Spanish |

| Genre | Magic realism |

| Publisher | Editorial Sudamericana,

|

|

Publication date

|

1967 |

|

Published in English

|

1970 |

| OCLC | 17522865 |

One Hundred Years of Solitude (Spanish: Cien años de soledad) is a famous novel written in 1967 by Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez. It tells the story of the Buendía family over many generations. The family's leader, José Arcadio Buendía, founded a made-up town called Macondo. Many people consider this book to be one of the greatest novels ever written.

The book is known for its "magical realism" style. This means that magical or impossible things happen in a very normal way, as if they are part of everyday life. This style made One Hundred Years of Solitude a very important book during the "Latin American Boom" of the 1960s and 1970s, a time when many great Latin American authors became famous.

Since it was first published in May 1967, One Hundred Years of Solitude has been translated into 46 languages. More than 50 million copies have been sold worldwide! It is seen as García Márquez's best work and is a very important book in both Hispanic and world literature.

Contents

About the Author and the Book

Gabriel García Márquez was one of four famous Latin American writers who became well-known during the "Latin American Boom." The others were Mario Vargas Llosa from Peru, Julio Cortázar from Argentina, and Carlos Fuentes from Mexico. One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967) made García Márquez internationally famous for his use of magical realism in Latin American stories.

What the Story is About

One Hundred Years of Solitude tells the story of seven generations of the Buendía family in their town of Macondo.

A big idea in the book is that history keeps repeating itself in Macondo. The characters often find themselves doing the same things or facing the same problems as their ancestors. This shows how the past can strongly influence the future.

García Márquez uses colors as symbols in the story. Yellow and gold are used often. Gold can mean a search for money and power. Yellow often represents big changes, destruction, or even death.

The idea of a "glass city" appears to José Arcadio Buendía in a dream. This dream leads him to choose the location for Macondo. But the glass city also hints at Macondo's future. It suggests that the town's fate is already set, and it might eventually disappear like a mirage. This can be seen as a symbol for how Latin American history has often been shaped by outside forces, leading to certain outcomes.

The novel is a great example of magical realism. It combines many years of history and its effects into an interesting story.

Main Ideas in the Book

The book explores many deep ideas. It shows the ups and downs of the town of Macondo and the Buendía family. It captures many parts of life: funny moments, sad times, and surprising events.

Magic and Reality: What is Real?

Critics often point to books like One Hundred Years of Solitude as perfect examples of magic realism. In this style, amazing or supernatural events are shown as normal. At the same time, everyday things can seem magical or unusual. The term "magic realism" was first used by a German art critic named Franz Roh in 1925.

The novel tells a made-up story in a made-up place. The amazing events and characters are not real. However, García Márquez uses this fantastic story to share a true message about history. He uses magical events to explain real-life situations. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, myths and history blend together. The myths help to tell the history to the reader. It becomes hard to tell what is real and what is fiction.

Magic realism is a key part of the novel. It mixes ordinary life with extraordinary events. This makes the world of Macondo feel magical. It's not just a place, but also a way of thinking. When you read the book, you have to be ready for anything the author imagines.

García Márquez blends the real and the magical by keeping the same calm way of telling the story. He describes amazing events as if they are not surprising at all. This makes the extraordinary seem less unusual, perfectly mixing the real with the magical. This calm tone also makes it harder for the reader to question the strange events. It makes you wonder about the limits of what is real.

The author is very good at mixing everyday life with miracles. He combines history with amazing tales, and real feelings with wild imagination. This book is a revolutionary story that gives a voice to Latin America. It shows a Latin America that wants to be independent and original.

The Feeling of Being Alone

Perhaps the most important idea in the book is solitude, or being alone. Macondo was founded deep in the jungles of Colombia. The town's isolation can represent how colonies in Latin America were often cut off from the rest of the world. Because they are isolated, the Buendía family members become more and more solitary and focused on themselves.

Each family member often lives only for themselves. This can represent the rich, land-owning families who became powerful in Latin America. This self-centeredness is seen in characters like Aureliano, who lives in his own world. Another example is Remedios the Beauty, who accidentally causes trouble for men who love her because she lives in her own reality. It often seems like no character can find true love or escape their own self-centeredness.

However, the selfishness of the Buendía family starts to change with Aureliano Segundo and Petra Cotes. They find a way to help each other and others during a tough time in Macondo. They even find love. This pattern is repeated by Aureliano Babilonia and Amaranta Úrsula. They have a child, and Amaranta Úrsula believes this child will bring a fresh start for the family. But the child is born with a pig's tail, which was a long-feared curse.

Even so, the appearance of love shows a change in Macondo, even if it leads to the town's end. The book's ending might be García Márquez's hopeful idea for the future of Latin America.

Time: Moving Forward and Repeating

One Hundred Years of Solitude explores several ideas about time. While the story moves forward in a straight line, García Márquez also shows time in other ways:

- He uses the idea of history repeating itself. This is shown through the Buendía family members having the same names and traits over six generations. For example, all the José Arcadios are curious and strong. The Aurelianos are often quiet and keep to themselves. This repetition shows how individuals and the town keep making the same mistakes.

- The book also looks at the idea of timelessness, or things that seem to last forever, even within a normal lifespan. A good example is the alchemist's laboratory in the Buendía home. This lab was set up by Melquíades early in the story and stays mostly the same throughout. It's a place where the male Buendía characters can be alone. They might try to understand the world with logic, like José Arcadio Buendía, or endlessly create and destroy golden fish, like Colonel Aureliano Buendía.

- Even though the story mostly moves forward, it also has many jumps in time. There are flashbacks to past events and quick looks into the future.

Being Elite

Another idea in One Hundred Years of Solitude is the idea of the Buendía family being "elite." Gabriel García Márquez shows his thoughts on the wealthy families in Latin America through this story. He shows a high-status family who are so focused on themselves that they cannot learn from their past mistakes.

Movies and Plays Based on the Book

One Hundred Years of Solitude has had a huge impact on the world of books. It is the author's best-selling and most translated work. However, there have been no movies made from it because García Márquez never agreed to sell the rights.

On March 6, 2019, García Márquez's son, Rodrigo García Barcha, announced that Netflix was planning to make a TV series based on the book. It was originally set for release in 2020, but development is still ongoing as of December 2021.

There have been some unofficial adaptations. Shuji Terayama created a play called One Hundred Years of Solitude and a film called Farewell to the Ark. These are loosely based on García Márquez's novel but are set in Japanese culture and history.

See also

In Spanish: Cien años de soledad para niños

In Spanish: Cien años de soledad para niños

- Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century

- List of best-selling books

| Aaron Henry |

| T. R. M. Howard |

| Jesse Jackson |