Gabriel García Márquez facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gabriel García Márquez

|

|

|---|---|

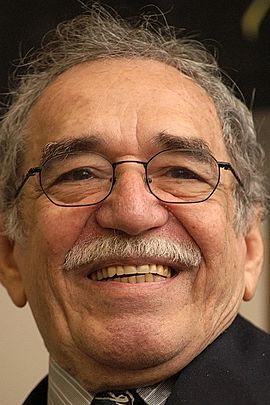

García Márquez in 2002

|

|

| Born | Gabriel José García Márquez 6 March 1927 Aracataca, Colombia |

| Died | 17 April 2014 (aged 87) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Language | Spanish |

| Alma mater | National University of Colombia University of Cartagena |

| Genre |

|

| Literary movement | |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse |

Mercedes Barcha

(m. 1958) |

| Children | 3, including Rodrigo García |

| Signature | |

Gabriel García Márquez (born March 6, 1927 – died April 17, 2014) was a very famous writer from Colombia. People often called him Gabo or Gabito. He wrote many novels, short stories, and even movie scripts. He is known as one of the most important writers of the 20th century.

García Márquez won the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 1972. He also received the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature. This is one of the biggest awards a writer can get. When he passed away in 2014, the president of Colombia called him "the greatest Colombian who ever lived."

Contents

Early Life in Colombia

Gabriel García Márquez was born in a small town called Aracataca, Colombia. This was on March 6, 1927. His parents were Gabriel Eligio García and Luisa Santiaga Márquez Iguarán. Soon after he was born, his parents moved away. Young Gabriel stayed in Aracataca and was raised by his grandparents.

His grandparents had a big influence on him. His grandfather, Colonel Nicolás Ricardo Márquez Mejía, was a brave war veteran. He told Gabriel many stories about history and real-life events. He also taught Gabriel new words from the dictionary.

His grandmother, Doña Tranquilina Iguarán Cotes, was also very important. She told amazing stories about ghosts and strange events. She made these extraordinary tales sound completely normal. This way of storytelling later inspired Gabriel's most famous book, One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Education and Becoming a Writer

Gabriel started his formal schooling in Barranquilla, a port city. He was a quiet boy who enjoyed writing funny poems and drawing comics. His classmates even called him El Viejo, meaning "The Old Man."

He later studied in Bogotá and Zipaquirá. After high school, he went to the National University of Colombia to study law. But he spent most of his time reading fiction books. He loved the idea of writing stories that mixed normal life with extraordinary events. This was like his grandmother's style.

In 1947, he published his first story, "La tercera resignación." Even though he loved writing, he continued studying law to please his father. However, after some big events in Bogotá, his university closed. He then moved to Cartagena and started working as a reporter. In 1950, he decided to focus only on journalism. He moved to Barranquilla to work for a newspaper. Even though he never finished his law degree, he became a very successful writer.

Political Views

García Márquez believed in fairness and helping people. His political ideas came from his grandfather. His grandfather was a Liberal and told him stories about past conflicts. These stories made Gabriel want to speak up against unfairness in the world. He believed in a society where everyone was treated equally.

He was also friends with Fidel Castro, the leader of Cuba. He admired some things about the Cuban Revolution. But he also tried to help improve things in the country. His views were always about standing up for what he believed was right.

Marriage and Family Life

Gabriel García Márquez met Mercedes Barcha when they were young. He was 12, and she was 9. They got married in 1958. The next year, their first son, Rodrigo García, was born. Rodrigo is now a film director.

In 1961, the family moved to Mexico City. Gabriel had always wanted to see the southern United States because it inspired other writers he admired. Three years later, their second son, Gonzalo García, was born in Mexico. Gonzalo is a graphic designer. In 2022, it was shared that García Márquez also had a daughter named Indira Cato. She is a documentary producer in Mexico City.

Writing Career and Magic Realism

García Márquez began as a journalist. He wrote many non-fiction books and short stories. But he is most famous for his novels. These include One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981), and Love in the Time of Cholera (1985).

His books became very popular and received great reviews. He helped make a writing style called magic realism famous. This style mixes magical things into everyday, realistic situations. Many of his stories take place in a made-up village called Macondo. This village was inspired by his hometown, Aracataca. A common theme in his books is solitude, which means being alone.

García Márquez sometimes left out small details in his stories. This made readers think more and become more involved in the story. For example, in No One Writes to the Colonel, the main characters do not have names.

One Hundred Years of Solitude

One Hundred Years of Solitude is his most famous book. To write it, García Márquez sold his car. This was so his family would have money to live on. He wrote every day for 18 months. His wife had to get food and pay rent on credit.

When the book was published in 1967, it was a huge success. It sold over 50 million copies. The story is about several generations of the Buendía family. It follows them as they create the fictional village of Macondo. The book shows their adventures, challenges, and family life.

This novel helped him win the Nobel Prize. Many people consider it a must-read book. Even former US President Bill Clinton said it was his favorite novel.

Films and Opera

García Márquez's writing is often described as very visual. He said his stories often started with a "visual image." So it is not surprising that he worked a lot with films. He was a film critic and helped run a film institute in Havana. He also wrote several screenplays (movie scripts).

Some of his screenplays include Tiempo de morir (1966) and Un señor muy viejo con unas alas enormes (1988). Many of his stories have also been made into movies by other directors. For example, Chronicle of a Death Foretold became a film in 1987. Love in the Time of Cholera was made into a movie in 2007. His novel Of Love and Other Demons was even turned into an opera in 2008.

Death and Legacy

Gabriel García Márquez passed away from pneumonia on April 17, 2014. He was 87 years old. He died in Mexico City, where he had lived for many years. His body was cremated in a private ceremony.

A formal ceremony was held in Mexico City. The presidents of Colombia and Mexico attended. People in his hometown of Aracataca also held a special memorial. His writings are a very important part of Latin American literature. His work encouraged critics to look at literature in new ways. After his death, his family gave his papers and personal items to The University of Texas at Austin. This was so people could study his work.

Nobel Prize in Literature

García Márquez received the Nobel Prize in Literature on December 10, 1982. He won "for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent's life and conflicts." His acceptance speech was called "The Solitude of Latin America."

He was the first Colombian writer to win this award. He was also the fourth Latin American to receive it. He felt that the prize was not just for him. He believed it was a way to honor all of Latin American literature.

List of Works

Novels

- In Evil Hour (1962)

- One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967)

- The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975)

- Love in the Time of Cholera (1985)

- The General in His Labyrinth (1989)

- Of Love and Other Demons (1994)

Novellas

- Leaf Storm (1955)

- No One Writes to the Colonel (1961)

- Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981)

Short Story Collections

- Eyes of a Blue Dog (1947)

- Big Mama's Funeral (1962)

- The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and Her Heartless Grandmother (1972)

- Collected Stories (1984)

- Strange Pilgrims (1993)

Non-fiction

- The Story of a Shipwrecked Sailor (1970)

- The Solitude of Latin America (1982)

- The Fragrance of Guava (1982, with Plinio Apuleyo Mendoza)

- Clandestine in Chile (1986)

- Changing the History of Africa: Angola and Namibia (1991, with David Deutschmann)

- News of a Kidnapping (1996)

- A Country for Children (1998)

- Living to Tell the Tale (2002)

Films He Wrote

| Year | Film | Credited as | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Director | Writer | ||||||

| 1954 | The Blue Lobster | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 1964 | The Golden Cockerel | Yes | |||||

| 1965 | Love, Love, Love (Lola de mi vida segment) | Yes | |||||

| 1966 | Time to Die | Yes | |||||

| 1967 | Dangerous Game | Yes | |||||

| 1968 | 4 contra el crimen | Yes | |||||

| 1974 | Presage | Yes | |||||

| 1979 | Mary my Dearest | Yes | |||||

| 1979 | The Year of the Plague | Yes | |||||

| 1983 | Eréndira | Yes | |||||

| 1985 | Time to Die | Yes | |||||

| 1988 | A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings | Yes | |||||

| 1988 | Fable of the Beautiful Pigeon Fancier | Yes | |||||

| 1989 | A Happy Sunday | Yes | |||||

| 1989 | Letters from the Park | Yes | |||||

| 1989 | Miracle in Rome | Yes | |||||

| 1990 | Don't Fool with Love: The Two Way Mirror | Yes | |||||

| 1991 | Far Apart | Yes | |||||

| 1991 | La María | Yes | |||||

| 1992 | Me alquilo para soñar | Yes | |||||

| 1993 | Crónicas de una generación trágica | Yes | |||||

| 1996 | Oedipus Mayor | Yes | |||||

| 1996 | Saturday Night Thief | Yes | |||||

| 2001 | The Invisible Children | Yes | |||||

| 2006 | ZA 05. Lo viejo y lo nuevo | Yes | |||||

| 2011 | Lessons for a Kiss | Yes | |||||

Movies Based on His Works

- There Are No Thieves in This Village (1965)

- The Widow of Montiel (1979)

- Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1987)

- No One Writes to the Colonel (1999)

- Love in the Time of Cholera (2007)

- Of Love and Other Demons (2009)

- Encanto (2021, Walt Disney Animation Studios)

See Also

In Spanish: Gabriel García Márquez para niños

In Spanish: Gabriel García Márquez para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |