Italo Calvino facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

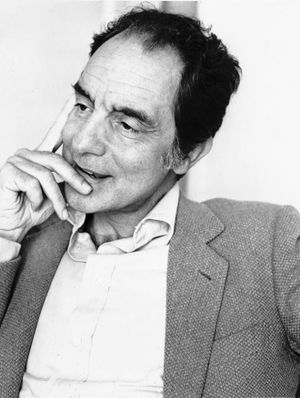

Italo Calvino

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Italo Giovanni Calvino Mameli 15 October 1923 Santiago de Las Vegas, Cuba |

| Died | 19 September 1985 (aged 61) Siena, Tuscany, Italy |

| Resting place | Garden cemetery of Castiglione della Pescaia, Italy |

| Occupation | Writer, journalist |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Literary movement | Oulipo, neorealism, Postmodernism |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse | Esther Judith Singer |

| Children | Giovanna |

Italo Calvino (born October 15, 1923 – died September 19, 1985) was a famous Italian writer and journalist. He is known for his amazing stories that often mix real life with fantasy. Some of his most popular books include Our Ancestors (a trilogy of three novels), the short story collection Cosmicomics, and the novels Invisible Cities and If on a winter's night a traveler.

Many people in Britain, Australia, and the United States loved his books. When he passed away, he was the most translated Italian writer of his time, meaning his books were available in many different languages around the world.

Italo Calvino is buried in a garden cemetery in Castiglione della Pescaia, a town in Tuscany, Italy.

Contents

Italo Calvino's Early Life and Family

Born in Cuba, Raised in Italy

Italo Calvino was born in Santiago de las Vegas, a town near Havana, Cuba, in 1923. His father, Mario, was a scientist who studied plants and taught about farming and flowers. Mario was born in Sanremo, Italy, and had moved to Mexico before going to Cuba for scientific work. Italo's father had interesting ideas, having been a follower of Kropotkin (a type of anarchist) and later a Socialist.

Calvino's mother, Giuliana "Eva" Mameli, was also a plant scientist and a university professor. She was from Sassari, Italy. Eva was a pacifist, meaning she believed in peace and avoiding war. She gave Italo his unique first name to remind him of his Italian background. Italo later joked that the name sounded "belligerently nationalist" since he ended up growing up in Italy anyway!

Childhood in Sanremo

In 1925, when Italo was less than two years old, his family moved back to Italy. They settled in Sanremo on the coast. His brother, Floriano, who later became a well-known geologist, was born there in 1927.

The family lived in a special house called Villa Meridiana, which was also a place where they experimented with growing flowers. They also spent time on their farm in the hills behind Sanremo. Here, Italo's father grew unusual fruits like avocado and grapefruit. The beautiful forests and animals that appear in Calvino's early stories, like The Baron in the Trees, came from his experiences growing up in this natural setting. Calvino often said that Sanremo kept appearing in his books. He and Floriano would climb the trees on their property and read adventure stories for hours.

Italo found it hard to talk to his father. He wrote about this in his memoir, The Road to San Giovanni, saying they were both talkative but became silent around each other. As a child, Calvino loved Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book. He felt like the "black sheep" of his family because they valued science more than literature. He also loved American movies, cartoons, drawing, poetry, and theater.

Growing Up During Difficult Times

Calvino remembered a scary event from his childhood: a professor who was attacked by Benito Mussolini's Blackshirts (a group supporting the Fascist party). This showed him the harsh realities of the time.

His parents were free-thinkers who strongly disliked the ruling National Fascist Party. They didn't give Italo or his brother a religious education. Italo went to an English nursery school and then a Protestant elementary school. For high school, he attended a state school where he was excused from religion classes. He often had to explain why he didn't follow the majority's beliefs. This experience made him "tolerant of others' opinions," especially about religion.

In 1938, he became friends with Eugenio Scalfari, who later founded important Italian newspapers. They shared a desk and discussed politics, which helped Calvino become more aware of the world around him.

Italo Calvino's Experiences in World War II

University and Resistance

In 1941, Calvino started studying agriculture at the University of Turin, partly to please his family. But secretly, he wanted to be a playwright and read many anti-Fascist books. He later moved to the University of Florence in 1943.

By the end of 1943, Germany had taken over parts of Italy, and Benito Mussolini set up a new government in the north. Calvino, who was 20, refused to join the army and went into hiding. He read a lot and decided that the communists were the best organized group fighting against the Fascists.

In 1944, his mother encouraged him and his brother to join the Italian Resistance, which was a secret movement fighting against the Fascists and Nazis. Calvino joined a Communist group called the Garibaldi Brigades and fought in the mountains for 20 months until Italy was freed in 1945. Because he refused to join the army, his parents were held hostage by the Nazis for a long time. Calvino admired his mother's bravery during this difficult period.

Life After the War and Writing Career

Starting as a Writer

After the war, Calvino moved to Turin in 1945. He changed his university studies from agriculture to arts. In 1946, a famous writer named Elio Vittorini helped him publish his first short story, "Andato al comando" ("Gone to Headquarters"). The war had given him many ideas for his writing and made him even more committed to the Communist cause. He officially joined the Italian Communist Party.

In 1947, he finished his university degree with a paper on the writer Joseph Conrad. He also got a job at the Einaudi publishing house, where he met many important writers and thinkers like Cesare Pavese and Natalia Ginzburg. He also worked as a journalist for the Communist newspaper L'Unità.

His first novel, The Path to the Nest of Spiders, was published in 1947 and was a big success. It sold over 5,000 copies, which was a lot for Italy at that time. This book marked the beginning of Calvino's "neorealist" period, where he wrote about real-life events. A writer named Pavese described him as a "squirrel of the pen" who "climbed into the trees... to observe partisan life as a fable of the forest."

Exploring New Styles

In 1949, his collection of stories about his war experiences, The Crow Comes Last, was also praised. However, Calvino found it hard to write his next novel. He went back to work at Einaudi publishing house in 1950, helping to edit books. This job helped him improve his own writing and discover new authors.

In 1951, he visited the Soviet Union as a journalist. While there, he learned that his father had passed away. His articles from this trip won a journalism prize.

Calvino tried writing three more realistic novels, but he felt they weren't good enough. He then realized he should write what came naturally to him, stories he would love to read himself. This led to The Cloven Viscount in 1952. This book was written in just 30 days! It tells the story of a viscount who is split in half by a cannonball. This story used elements of fable and fantasy and showed Calvino's growing doubts about politics during the Cold War. This book made him known as a modern "fabulist," someone who writes fables.

In 1954, he was asked to create a collection of Italian folktales, similar to the Brothers Grimm in Germany. For two years, he gathered and translated 200 of the best tales from different Italian dialects into standard Italian, which became Italian Folktales (1956).

Leaving the Communist Party

In 1957, Calvino left the Italian Communist Party. He was disappointed by the Soviet Union's actions in Hungary in 1956 and the truth about Joseph Stalin's crimes. He explained his reasons in a letter published in L'Unità. After this, he stopped being actively involved in politics and never joined another party.

He then started writing The Baron in the Trees, which he finished in just three months. This fantasy novel explores the idea of an intellectual's role in a world where old beliefs are falling apart. He also started co-editing a cultural magazine called 'Il Menabò, which focused on literature in the modern industrial age.

Travels and Family Life

From 1959 to 1960, Calvino visited the United States for six months, spending most of his time in New York. He was very impressed by the "New World." He wrote letters describing his trip, which were later published.

In 1962, Calvino met Esther Judith Singer, an Argentinian translator. They married in 1964 in Havana, Cuba, where he had been born. During this trip, he even met Che Guevara, a famous revolutionary. In 1965, their daughter, Giovanna, was born in Rome. Calvino continued to write, publishing some of his "Cosmicomics" stories in a literary magazine.

Later Years and Legacy

Moving to Paris and New Influences

In 1966, Calvino felt a big change in his life, calling it an "intellectual depression." He felt he was moving from youth into "old age."

In 1967, he and his family moved to Paris, France. There, he was invited to join a group of experimental writers called Oulipo. In this group, he met other famous writers like Georges Perec, who influenced his later work. He also started writing regularly for the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera. During the summers, he enjoyed spending time in his house in Roccamare, Tuscany.

Awards and Final Years

Calvino received many awards for his writing, including the Austrian State Prize for European Literature in 1976 and the French Légion d'honneur in 1981. He also traveled to Mexico, Japan, and the United States, where he gave lectures.

After his mother passed away in 1978, Calvino sold his family home in Sanremo. He moved to Rome in 1980. In the summer of 1985, he was preparing a series of lectures about literature to give at Harvard University in the United States. However, on September 6, he was admitted to a hospital in Siena and sadly passed away on September 19 from a brain hemorrhage. His lecture notes were published after his death as Six Memos for the Next Millennium.

Lasting Impact

Italo Calvino's work continues to inspire people around the world. A school in Moscow, Russia, the Scuola Italiana Italo Calvino, is named after him. There's even a crater on the planet Mercury and an asteroid named after him! The Italo Calvino Prize is given every year for fiction written in a style similar to his unique and imaginative stories.

His stories have also been adapted into films and television shows, showing how his creative ideas continue to live on.

Authors Italo Calvino Helped Publish

- Mario Rigoni Stern

- Gianni Celati

- Andrea De Carlo

- Daniele Del Giudice

- Leonardo Sciascia

Selected Film Projects

- Boccaccio '70, 1962 (he helped write a part of this movie)

- L'Amore difficile, 1963 (he wrote a part of this movie)

- Tiko and the Shark, 1964 (he helped write the movie script)

Movies and TV Shows Based on His Works

- The Nonexistent Knight by Pino Zac, 1969 (an Italian animated film based on his novel)

- Amores dificiles by Ana Luisa Ligouri, 1983 (a short Mexican film)

- L'Aventure d'une baigneuse by Philippe Donzelot, 1991 (a short French film based on one of his stories)

- Fantaghirò by Lamberto Bava, 1991 (a TV show based on a folktale from his Italian Folktales collection)

- Palookaville by Alan Taylor, 1995 (an American film based on several of his short stories)

- Solidarity by Nancy Kiang, 2006 (a short American film)

- Conscience by Yu-Hsiu Camille Chen, 2009 (a short Australian film)

- "La Luna" by Enrico Casarosa, 2011 (a short American film)

Films About Italo Calvino

- Damian Pettigrew, Lo specchio di Calvino (Inside Italo, 2012). This movie shows the Italian writer and critic Pietro Citati as Italo Calvino. It also includes real conversations with Calvino from before he died and old footage from TV archives.

Awards He Received

- 1946 – L'Unità Prize (shared) for Minefield

- 1947 – Riccione Prize for The Path to the Nest of Spiders

- 1952 – Saint-Vincent Prize

- 1957 – Viareggio Prize for The Baron in the Trees

- 1959 – Bagutta Prize

- 1960 – Salento Prize for Our Ancestors

- 1963 – International Charles Veillon Prize for The Watcher

- 1970 – Asti Prize

- 1972 – Feltrinelli Prize for Invisible Cities

- 1976 – Austrian State Prize for European Literature

- 1981 – Legion of Honour

- 1982 – World Fantasy Award – Life Achievement

See also

In Spanish: Italo Calvino para niños

In Spanish: Italo Calvino para niños