Harold Bloom facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harold Bloom

|

|

|---|---|

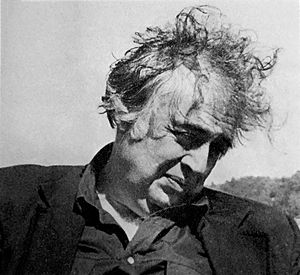

Bloom in 1986

|

|

| Born | July 11, 1930 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | October 14, 2019 (aged 89) New Haven, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation | Literary critic, writer, professor |

| Education | Cornell University (BA) Yale University (MA, PhD) Pembroke College, Cambridge |

| Literary movement | Aestheticism, Romanticism |

| Years active | 1955–2019 |

| Spouse |

Jeanne Gould

(m. 1958) |

| Children | 2 |

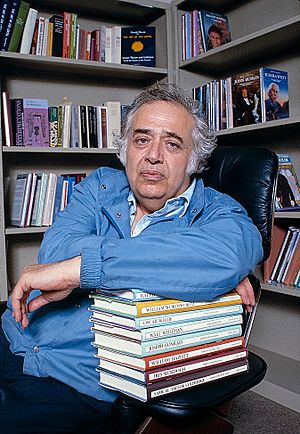

Harold Bloom (born July 11, 1930 – died October 14, 2019) was a very famous American literary critic. He was also a professor at Yale University. In 2017, many people called him "probably the most famous literary critic in the English-speaking world."

After his first book came out in 1959, Bloom wrote over 50 more books. More than 40 of these were about literature. He also wrote books about religion and even a novel. He helped edit hundreds of collections of writings by important thinkers. Bloom's books have been translated into more than 40 languages. He was chosen to be part of the American Philosophical Society in 1995.

Bloom was a strong supporter of the traditional Western canon. This means he believed in the importance of classic books from Western culture. He felt that many university departments were focusing too much on what he called the "School of Resentment." This group included people who focused on multiculturalism, feminism, and Marxism in their literary studies. Bloom studied at Yale University, the University of Cambridge, and Cornell University.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Harold Bloom was born in New York City on July 11, 1930. His parents were Paula and William Bloom. He grew up in the Bronx. His family was Orthodox Jewish and spoke Yiddish at home. He also learned Hebrew. He learned English when he was six years old.

His father worked with clothes and was born in Odessa. His mother was a homemaker and was from near Brest Litovsk in what is now Belarus. Harold had three older sisters and an older brother. He was the last of his siblings to pass away.

As a boy, Bloom loved to read poetry. He was especially inspired by a book called Collected Poems by Hart Crane. This book made him fascinated with poetry for his whole life. He went to the Bronx High School of Science. Later, he earned a bachelor's degree from Cornell in 1951. He then got his PhD from Yale in 1955. In 1954–55, he was a Fulbright Scholar at Pembroke College, Cambridge.

Teaching Career

Bloom taught in the English Department at Yale from 1955 until 2019. He taught his last class just four days before he died. In 1985, he received a special award called a MacArthur Fellowship. From 1988 to 2004, Bloom was also a professor at New York University, while still teaching at Yale.

He was known for being kind to his students and friends. He would often call both male and female students "my dear."

Later Life and Passing

Bloom married Jeanne Gould in 1958. They had two children together. In an interview in 2005, his wife said they were both atheists. However, Bloom disagreed, saying, "No, no I'm not an atheist. It's no fun being an atheist."

Bloom continued teaching even when he was very old. He once joked that he would have to be carried out of the classroom "in a great big body bag." He had heart surgery in 2002 and broke his back in 2008. He passed away at a hospital in New Haven, Connecticut, on October 14, 2019. He was 89 years old.

Writing About Literature

Defending Romanticism

Bloom started his writing career by focusing on important Romantic poets. These included Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Blake, W. B. Yeats, and Wallace Stevens. He wrote books defending these poets. He argued against critics who were influenced by writers like T. S. Eliot. Bloom's first book, Shelley's Myth-making, even said that many critics at the time were careless when reading Shelley's poems.

Understanding Influence

After a difficult time in the late 1960s, Bloom became very interested in Ralph Waldo Emerson, Sigmund Freud, and old spiritual traditions. These included Gnosticism, Kabbalah, and Hermeticism. In an interview in 2003, Bloom said he thought of himself as a "Jewish Gnostic." He explained that he used "Gnostic" in a broad way. He said he was Jewish and came from Yiddish culture. But he couldn't understand a God who was all-powerful and all-knowing but allowed terrible events like the Nazi death camps.

Because of his new interests, he started writing books about how poets struggle to create their own unique ideas. This happens when they are inspired by older poets but don't want to just copy them.

One of his first books on this topic was Yeats. In this book, Bloom explained his new way of looking at criticism. He said, "Poetic influence... is a variety of melancholy or the anxiety-principle." This means new poets feel inspired by older poets. But then they might feel upset when they realize these older poets have already said everything they want to say. It's like they can't be the very first person to name things.

To get past this feeling, Bloom said new poets must believe that older poets made mistakes or didn't fully achieve their vision. This leaves a chance for the new poets to add something new. So, their love for their heroes turns into a kind of friendly competition. Bloom's next book, The Anxiety of Influence, explored this idea. He explained how "strong poets" create their own unique style by "misreading" their older influences in a new way. "Weak poets," he said, just repeat old ideas.

Later Ideas and a Novel

Bloom continued to develop his ideas about influence in other books. He also wrote his only novel, The Flight to Lucifer. This book was a sequel to a fantasy novel he admired called A Voyage to Arcturus.

Writing About Religion

Bloom then started writing more about religion. In The Book of J (1990), he and David Rosenberg suggested that one of the oldest parts of the Bible was written by a great literary artist. They even thought this writer might have been a woman connected to the courts of King David and King Solomon.

In Jesus and Yahweh: The Names Divine (2004), he looked at Yahweh and Jesus of Nazareth as literary characters. He also discussed how Christianity and Judaism are different.

In The American Religion (1992), Bloom studied different types of Protestant faiths in the United States. He argued that many of them were more like gnosticism than traditional Christianity. He predicted that Mormon and Pentecostal churches would become more popular than mainstream Protestant groups.

The Western Canon

The Western Canon (1994) was a major book by Bloom. It looked at important literary works from Europe and the Americas since the 14th century. He focused on 26 works that he thought were amazing and represented their nations and the Western canon.

Bloom's main goal in this book was to protect literature from critics he called the "School of Resentment." These were mostly academic critics who believed reading should have a social purpose. Bloom argued that reading should be for personal enjoyment and self-discovery. He felt it was not meant to improve society. He wrote that the idea of reading someone from your own background instead of Shakespeare to help others was "one of the oddest illusions ever promoted." He believed that politics should not be part of literary criticism. For example, he said a feminist or Marxist reading of Hamlet would tell you about feminism or Marxism, but not much about Hamlet itself.

Bloom also created a list of Western works that he thought were classic or could become classics. He later said he made the list quickly and didn't fully stand by it.

Writing About Shakespeare

Bloom deeply admired William Shakespeare. He believed Shakespeare was the most important writer in the Western canon. In his book Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (1998), Bloom analyzed each of Shakespeare's 38 plays. He called 24 of them "masterpieces."

Bloom believed that Shakespeare "invented" humanity. He thought Shakespeare showed us how we "overhear" ourselves, which helps us change. He saw characters like Sir John Falstaff and Hamlet as representing self-satisfaction and self-loathing. Bloom felt that these two characters, along with Iago and Cleopatra, were the most interesting to think about.

Bloom again criticized the "School of Resentment" in this book. He felt they failed to understand Shakespeare's universal appeal. He said Shakespeare was the only truly multicultural author because his plays are popular everywhere.

Later Works

Bloom continued to write many books in the 2000s and 2010s. These included How to Read and Why (2000) and Genius: A Mosaic of One Hundred Exemplary Creative Minds (2003). He also wrote Hamlet: Poem Unlimited (2003) to add more thoughts about Hamlet.

He combined his religious and literary criticism in Where Shall Wisdom Be Found (2004). He also returned more fully to religious criticism with Jesus and Yahweh: The Names Divine (2005). During these years, he also put together and introduced several large collections of poetry.

Bloom appeared in a documentary called Apparition of the Eternal Church (2006). This film showed people's reactions to hearing a piece of music by Olivier Messiaen for the first time.

His book The Anatomy of Influence: Literature as a Way of Life was published in 2011. He also worked on other projects, including a history of American literature and a memoir. His last book published during his lifetime was Possessed by Memory: The Inward Light of Criticism (2019). He was also working on a play about Walt Whitman before he died.

Influence on Others

In 1986, Bloom said that Northrop Frye was an important influence on his own ideas. He said that Frye's book Fearful Symmetry "ravished my heart away." However, in 2011, Bloom wrote that he no longer had the patience to read Frye's work.

Later in his career, Bloom also highlighted the importance of earlier critics. These included William Hazlitt, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walter Pater, A. C. Bradley, and Samuel Johnson. He called Johnson "unmatched by any critic in any nation before or after him."

Bloom's theory of poetic influence suggests that Western literature develops through borrowing and "misreading." Writers are inspired by previous writers and start by imitating them. But to create their own unique voice, they must make their work different. Bloom argued that truly powerful authors must "misread" older works to make space for their own new ideas.

People sometimes linked Bloom to a way of thinking called deconstruction. But Bloom himself said he only shared a few ideas with deconstructionists. He explained that he used a "negative thinking" approach, which came from a religious idea called negative theology.

Bloom's focus on the Western canon made people very interested in his opinions about modern writers. In the late 1980s, he said Samuel Beckett was "probably the most powerful living Western writer." After Beckett died in 1989, Bloom pointed to other authors as new main figures.

He admired British writers like Geoffrey Hill and Iris Murdoch. After Murdoch died, he liked novelists such as Peter Ackroyd, Will Self, John Banville, and A. S. Byatt.

In his 2003 book Genius, he called the Portuguese writer and Nobel Prize winner José Saramago "the most gifted novelist alive in the world today."

Among American novelists, he said in 2003 that four living writers deserved praise: Thomas Pynchon, Philip Roth, Cormac McCarthy, and Don DeLillo. He named their strongest works. He also greatly admired John Crowley. Before he died, he also liked the works of Joshua Cohen, William Giraldi, and Nell Freudenberger.

For American poets, in 1975, Bloom named Robert Penn Warren, James Merrill, John Ashbery, and Elizabeth Bishop as the most important. Later, he often included A. R. Ammons. He later called Henri Cole the most important American poet of the next generation. He also greatly admired Canadian poets Anne Carson and A. F. Moritz. He listed Jay Wright as one of the best living American poets after Ashbery's death.

Playwright Tony Kushner has said that Bloom was an important influence on his own work.

See also

In Spanish: Harold Bloom para niños

In Spanish: Harold Bloom para niños

- Covering cherub

- List of thinkers influenced by deconstruction

- School of resentment

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |