Hart Crane facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hart Crane

|

|

|---|---|

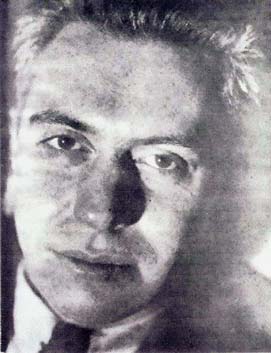

Crane in 1930

|

|

| Born | Harold Hart Crane July 21, 1899 Garrettsville, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | April 27, 1932 (aged 32) Gulf of Mexico |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Period | 1916–1932 |

| Notable works | The Bridge |

| Signature | |

|

|

|

|

|

Harold Hart Crane (July 21, 1899 – April 27, 1932) was an American poet. He wrote modern poetry, which was often known for being complex. His book White Buildings (1926) included famous poems like "Chaplinesque" and "Voyages." This book helped him become well-known in the literary world. His long poem The Bridge (1930) was inspired by the Brooklyn Bridge.

Crane was born in Garrettsville, Ohio. He left high school in Cleveland during his junior year and moved to New York City. He worked different jobs, including writing advertisements. In the early 1920s, some of Crane's poems were published in small but respected magazines. This helped him gain recognition before White Buildings was released. The Bridge was meant to be an uplifting poem about America. It was seen as a hopeful response to other poems of the time. Hart Crane died on April 27, 1932.

Some poets like William Carlos Williams and E. E. Cummings praised his work. Others, like Marianne Moore and Wallace Stevens, had criticisms. His last poem, "The Broken Tower" (1932), was not finished and was published after he died. Many writers and critics, including Robert Lowell and Tennessee Williams, have praised Crane's poetry.

Life of Hart Crane

Early Years

Hart Crane was born in Garrettsville, Ohio. His parents were Clarence A. Crane and Grace Edna Hart. His father was a successful businessman who made candy.

In 1894, his family moved to Warren, Ohio. His father started a maple syrup company there. In 1911, the family moved to Cleveland. Hart Crane started attending East High School around 1913.

Poetry Career

He has woven rose-vines

About the empty heart of night,

And vented his long mellowed wines

Of dreaming on the desert white

With searing sophistry.

And he tented with far thruths he would form

The transient bosoms from the thorny tree.

O Materna! to enrich thy gold head

And wavering shoulders with a new light shed

From penitence, must needs bring pain,

And with it song of minor, broken strain.

But you who hear the lamp whisper thru night

Can trace paths tear-wet, and forget all blight.

Crane's first published poem was "C33." It appeared in a journal called Bruno's Weekly in 1917. The poem was named after Oscar Wilde's prison cell. Crane left high school in Cleveland in December 1916 and moved to New York City. He promised his parents he would go to Columbia University later.

Crane took different jobs, including writing advertisements. He moved between friends' apartments in Manhattan. Between 1917 and 1924, he often traveled between New York and Cleveland. He worked as an advertising writer and in his father's factory.

In 1925, he briefly lived with Caroline Gordon and Allen Tate. He wrote to his mother and grandmother in 1924, describing his view from his home in Brooklyn:

Just imagine looking out your window directly on the East River with nothing intervening between your view of the Statue of Liberty, way down the harbour, and the marvelous beauty of Brooklyn Bridge close above you on your right! All of the great new skyscrapers of lower Manhattan are marshaled directly across from you, and there is a constant stream of tugs, liners, sail boats, etc in procession before you on the river! It's really a magnificent place to live. This section of Brooklyn is very old, but all the houses are in splendid condition and have not been invaded by foreigners...

New York was a very important place for Crane. Many of his poems are set there.

White Buildings (1926)

In the early 1920s, many literary magazines published Crane's poems. This helped him gain respect. His reputation grew stronger with the release of White Buildings in 1926. This book contains many of his most popular poems, including "For the Marriage of Faustus and Helen" and "Voyages."

Crane returned to New York in 1928 after a hurricane damaged his mother's family home in Cuba. He lived with friends and took temporary jobs. For a time, he lived in Brooklyn. He was very happy with the views from his home in Brooklyn Heights.

The Bridge (1930)

Crane first mentioned The Bridge in a letter in 1923. He wrote that it would be a very difficult poem to complete.

Crane moved to Paterson, New Jersey, in 1927. In 1928, he worked as a secretary for a stockbroker. He traveled to Europe in late 1928. In Paris in 1929, Harry Crosby offered Crane a place to stay to help him finish The Bridge. Crane spent several weeks there and wrote a part of the poem called "Cape Hatteras."

In June 1929, Crane returned to Paris. He had a problem at a cafe and was arrested. After six days in prison, Crosby paid his fine. Crane then returned to the United States, where he finished The Bridge. The poem was published in 1930. Some early reviews were not very positive, and Crane felt like a failure.

The Bridge was meant to be a hopeful poem about America. The Brooklyn Bridge is a main symbol in the poem. It was a starting point for Crane's ideas.

"The Broken Tower" (1932)

Crane visited his father in Ohio in 1931. He then went to Mexico in 1931–32 on a special writing grant. He experienced times of feeling very happy and then very sad. "The Broken Tower" was one of his last poems.

"The Broken Tower" was meant to be a poem about modern thinking. It has been interpreted in many ways by critics. Crane finished the poem two months before he died. It was first published in The New Republic after his death.

Death

Crane and his friend Peggy Cowley decided to return to New York on a ship called the Orizaba in April 1932. Crane's stepmother had invited him back to help with his father's estate, as his father had died the month before. This was the same ship he had taken to Cuba in 1926. The ship left Vera Cruz, Mexico on April 23 and stopped in Havana, Cuba on April 26.

Just before noon on April 27, 1932, Crane jumped from the ship into the Gulf of Mexico. A marker on his father's tombstone in Ohio says, "Harold Hart Crane 1899–1932 lost at sea."

Writing Style

Influences on His Work

Crane was greatly influenced by the poet T. S. Eliot, especially by his poem The Waste Land. Crane wanted The Bridge to show a more positive view of society than Eliot's poem. He first read The Waste Land in 1922.

Other poets who influenced Crane included Walt Whitman, William Blake, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Emily Dickinson. As a teenager, Crane also read works by Plato and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Poetic Style

Understanding His Poetry

When White Buildings was published, some people found Crane's poetry difficult to understand. The publisher Harcourt even rejected White Buildings at first. They said it was "the most perplexing kind of poetry." Even a young Tennessee Williams, who loved Crane's poetry, said he could "hardly understand a single line."

Crane knew his poetry was challenging. He wrote essays and letters to explain his ideas. He once wrote:

If the poet is to be held completely to the already evolved and exploited sequences of imagery and logic—what field of added consciousness and increased perceptions (the actual province of poetry, if not lullabies) can be expected when one has to relatively return to the alphabet every breath or two? In the minds of people who have sensitively read, seen, and experienced a great deal, isn't there a terminology something like short-hand as compared to usual description and dialectics, which the artist ought to be right in trusting as a reasonable connective agent toward fresh concepts, more inclusive evaluations?

He believed that new ways of life create new ways for people to express themselves. He felt that poetry should capture the voice of the present, even if it uses new and sometimes surprising language.

Accusations of Plagiarism

In 1926, Crane saw some poems by Samuel Greenberg, a poet who had died in 1917. Crane copied 42 of Greenberg's poems. Many of Crane's own poems used lines and phrases from Greenberg's work without saying where they came from. For example, Crane's poem "Emblems of Conduct" used only rearranged lines from Greenberg's poems.

This copying was not noticed for many years. In 1978, a book by Marc Simon showed how Crane had copied from Greenberg. Experts have different ideas about why Crane did this. Some, like writer Samuel R. Delany, believe Crane wanted to bring attention to the unknown poet. He might have wanted readers to discover the influence for themselves.

Influence and Legacy

Among Other Writers

Many artists admired Crane, including Eugene O'Neill, E. E. Cummings, and William Carlos Williams. Even though some critics like Ezra Pound did not like his work, others published it.

Lasting Impact

Later American poets, like John Berryman and Robert Lowell, said Crane was a big influence on them. They also wrote poems about him. Lowell believed Crane was the most important American poet of his time. He said Crane "got out more than anybody else" and captured the spirit of New York City.

Tennessee Williams said he wanted to be "given back to the sea" at the same spot where Hart Crane died. One of Williams's last plays explored Crane's relationship with his mother.

Literary critic Harold Bloom said that Crane, along with William Blake, first made him interested in literature when he was young. Bloom called Crane "a High Romantic in the era of High Modernism." He also wrote the introduction for a special edition of Crane's collected poems.

Poet Gerald Stern wrote in 2011 that Crane was able to create "a poetry that was tender, attentive, wise, and radically original," even though he died young. Stern felt that Crane's voice and vision had a strong effect on his own writing.

Beyond poetry, Crane's death inspired art by Jasper Johns, music by Elliott Carter, and a painting by Marsden Hartley.

Depictions in Media

Crane is the subject of The Broken Tower, a 2011 American student film. The actor James Franco wrote, directed, and starred in the movie. He based the story on a book about Hart Crane's life. Even though it was a student film, The Broken Tower was shown at a film festival and released on DVD.

Crane also appears as a character in stories by Samuel R. Delany and in The Illuminatus! Trilogy by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson.

See also

In Spanish: Hart Crane para niños

In Spanish: Hart Crane para niños

- Modernist poetry in English

- American poetry

- Appalachian Spring