Brooklyn Bridge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Brooklyn Bridge |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Coordinates | 40°42′21″N 73°59′47″W / 40.7057°N 73.9964°W |

| Carries | 5 lanes of roadway Elevated trains (until 1944) Streetcars (until 1950) Pedestrians and bicycles |

| Crosses | East River |

| Locale | New York City (Civic Center, Manhattan – Dumbo/Brooklyn Heights, Brooklyn) |

| Maintained by | New York City Department of Transportation |

| ID number | 22400119 |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Cable-stayed suspension bridge |

| Total length | 6,016 ft (1,833.7 m; 1.1 mi) |

| Width | 85 ft (25.9 m) |

| Height | 272 ft (82.9 m) (towers) |

| Longest span | 1,595.5 ft (486.3 m) |

| Clearance below | 127 ft (38.7 m) above mean high water |

| History | |

| Designer | John Augustus Roebling |

| Constructed by | New York Bridge Company |

| Opened | May 24, 1883 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 121,930 (2019) |

| Toll | Free (Manhattan-bound to FDR Drive north, and Brooklyn-bound) Variable congestion charge (Manhattan-bound to all other exits) |

|

Brooklyn Bridge

|

|

| Built | 1869–1883 |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000523 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | January 29, 1964 |

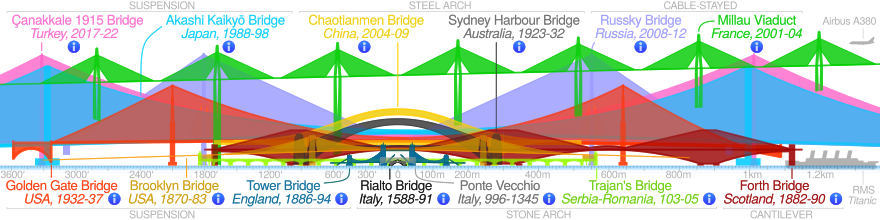

The Brooklyn Bridge is a famous suspension bridge in New York City. It connects the areas of Manhattan and Brooklyn by crossing the East River. When it opened on May 24, 1883, it was the first bridge to cross the East River. It was also the longest suspension bridge in the world at that time. Its main section stretched 1,595.5 feet (486.3 m) and its deck was 127 ft (38.7 m) above the water.

The bridge was first called the New York and Brooklyn Bridge or the East River Bridge. It was officially renamed the Brooklyn Bridge in 1915. Ideas for a bridge here started in the early 1800s. John A. Roebling designed the Brooklyn Bridge. His son, Washington Roebling, became the chief engineer and continued the design work. Washington's wife, Emily Warren Roebling, also helped a lot.

Construction began in 1870 and took over thirteen years. Many challenges arose because the design was so new. After it opened, the Brooklyn Bridge was changed several times. It carried horse-drawn vehicles, trains, and streetcars until 1950. Over the years, the bridge has been repaired and updated many times, including in the 1950s, 1980s, and 2010s.

The Brooklyn Bridge is one of five bridges that connect Manhattan Island to Long Island. It is a major tourist spot and a symbol of New York City. The bridge is recognized as a National Historic Landmark and a New York City landmark.

Exploring the Brooklyn Bridge

The Brooklyn Bridge is an early example of a suspension bridge that uses steel wires. It has a special design that combines parts of cable-stayed and suspension bridges. This means it has both straight-down and diagonal support cables. Its stone towers are built in a Neo-Gothic style, with pointed arches. The New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) takes care of the bridge.

The Bridge Deck

To allow ships to pass easily in the East River, the bridge has long ramps on both sides. These ramps raise the bridge from the ground. The entire bridge, including these ramps, is about 6,016 feet (1,834 m) long.

The Main Suspension Section

The main part of the bridge between the two towers is 1,595.5 feet (486.3 m) long and 85 feet (26 m) wide. This section can actually grow or shrink by about 14 to 16 inches due to temperature changes! Ships have 127 ft (38.7 m) of space to pass underneath at high tide.

The sections between each tower and the land are 930 feet (280 m) long. When the bridge was built, engineers did not yet know much about how wind affects bridges. So, John Roebling designed the Brooklyn Bridge to be much stronger than he thought it needed to be. This strong design helped it avoid many wind problems.

The main and side sections are held up by strong metal structures called trusses. These trusses run along the roadway and are 33 feet (10 m) deep. They help the bridge carry a total weight of 18,700 short tons (17,000 metric tons). These trusses are supported by ropes called suspender cables, which hang from the four main cables.

An elevated pathway for people walking and biking runs in the middle of the bridge. It is about 18 feet (5.5 m) above the car lanes. This path is usually 10 to 17 feet (3.0 to 5.2 m) wide.

Bridge Approaches

Each side of the bridge has a ramp leading up to it. The Brooklyn ramp is 971-foot (296 m) long, and the Manhattan ramp is 1,567-foot (478 m) long. These ramps have Renaissance-style arches made of stone.

Under the Manhattan approach, there was a popular skate park called the Brooklyn Banks. It used the bridge's support pillars as obstacles. In the mid-2010s, the Brooklyn Banks closed for bridge renovations. Skateboarders tried to save the park many times. In 2020, the city removed some bricks, leading to an online petition to save the banks. Some of the space under the Manhattan approach reopened as a park called the Arches in May 2023. Another section opened in November 2024.

The Bridge Cables

The Brooklyn Bridge has four main cables that stretch from the top of the towers and hold up the bridge deck. Two cables are on the outside of the roadways, and two are in the middle. Each main cable is 15.75 inches (40.0 cm) thick. They are made of 5,282 strong, galvanized steel wires bundled together. This was the first time this bundling method was used for a suspension bridge. Since the 2000s, these main cables have had special LED lights, making them look like a "necklace" at night.

There are also many smaller suspender cables that hang down from the main cables. Another 400 diagonal cables, called stays, extend from the towers. These cables work together to support the bridge deck. The original suspender cables were replaced in the 1980s with new steel ones.

Cable Anchorages

On each side of the bridge, there is a large stone structure called an anchorage. These anchorages hold the main cables firmly in place. They are huge, weighing 60,000 short tons (54,000 long tons; 54,000 t) each. The Manhattan anchorage sits on solid rock, while the Brooklyn anchorage rests on clay.

Inside the anchorages are large metal plates that connect to the main cables. These plates are linked to the cables by strong metal bars. The anchorages also have many hidden rooms and passages. In the past, some of these rooms under the Manhattan anchorage were rented out for storage, especially for wine, because they stayed cool. These vaults were closed to the public in the 1910s and 1920s but reopened later. Today, they are used to store maintenance equipment.

The Bridge Towers

The bridge's two towers are 278 feet (85 m) tall. They are made of limestone, granite, and a special cement. The stone blocks were brought from quarries in New York and Maine. The Manhattan tower used 46,945 cubic yards (35,892 m3) of stone, and the Brooklyn tower used 38,214 cubic yards (29,217 m3). Today, 56 LED lights shine on the towers at night.

Each tower has two pointed arches in the Gothic Revival style, through which the roadways pass. These arches are 117 feet (36 m) tall and 33.75 feet (10.29 m) wide.

Underwater Foundations (Caissons)

The towers stand on huge underwater boxes called caissons. These caissons are made of wood and filled with cement. Workers went inside these caissons to dig out the riverbed until they reached a solid foundation. The Manhattan caisson was larger and deeper, going 78.5 feet (23.9 m) below high water. The Brooklyn caisson was 44.5 feet (13.6 m) deep.

Working in the caissons was very dangerous due to the high air pressure. Many workers became sick with a condition called "caisson disease," now known as decompression sickness or "the bends." This sickness caused severe pain and could be paralyzing. Washington Roebling, the chief engineer, himself suffered from this sickness.

History of the Brooklyn Bridge

Early Planning

People started suggesting a bridge between Brooklyn and New York as early as 1800. At that time, the only way to travel between the two cities was by ferry. Many bridge designs were proposed, but building a high enough bridge over the busy East River was very difficult.

In 1857, John Augustus Roebling, a German engineer, suggested building a suspension bridge. He had already built other suspension bridges. In 1867, the New York State Senate approved the idea. The New York and Brooklyn Bridge Company was formed to build the bridge. The bridge was sometimes called the "Brooklyn Bridge" even then.

Roebling became the chief engineer and presented a grand plan. The bridge would be longer and taller than any before it. It would have roads and train tracks, and a raised pathway for people to enjoy. People were very excited about the project. However, some worried about the cost and difficulty.

In June 1869, John Roebling had a serious accident while surveying the bridge site. He later passed away from an infection. His 32-year-old son, Washington Roebling, took over as chief engineer. A powerful political group called Tammany Hall also became involved in the bridge's construction. Washington Roebling's wife, Emily Warren Roebling, played a huge role. After Washington became very ill from caisson disease, she helped him manage the project. She learned about engineering and communicated his instructions to the workers on site for 11 years.

Building the Bridge

Caisson Construction

Construction started on January 2, 1870, with the building of the caissons for the towers. The Brooklyn caisson was launched in March 1870. Workers used compressed air to dig out the riverbed inside the caisson. This was a very difficult and dangerous job. The Brooklyn caisson also caught fire once, causing delays. It finally reached its depth in March 1871.

The Manhattan caisson was built next, starting in May 1871. To prevent fire, it was lined with iron. Because this caisson went much deeper, many workers became sick with "the bends" (decompression sickness). The project doctor, Andrew Smith, treated many cases. Washington Roebling stopped digging when the caisson reached 78.5 feet (23.9 m) deep, deciding the ground was firm enough. The caisson was filled with concrete in July 1872.

Tower Construction

After the caissons were finished, the stone towers were built on top of them. This process took four years. Heavy stone blocks were lifted using a pulley system and steam engines. The work was dangerous, and some workers died from falls or other accidents.

Construction on the towers began in mid-1872. By August 1874, the arches of the Brooklyn tower were finished. The last stone on the Brooklyn tower was placed in June 1875, and the Manhattan tower was completed in July 1876. These towers were taller than almost any other building in the city at the time.

The project ran out of its initial budget in 1875. More money was approved by state lawmakers, with the condition that the cities would buy out private investors.

Cable Spinning

The first temporary wire was stretched across the river in August 1876. This wire was used to create a temporary footbridge for workers. The bridge's master mechanic, E. F. Farrington, was the first to cross on a special chair, watched by thousands of people. The temporary footbridge was finished in February 1877.

The main cables were spun starting in May 1877. This involved pulling thousands of steel wires across the river and bundling them together. During this time, the temporary footbridge was opened to visitors, and thousands crossed it.

A problem arose when it was discovered that a supplier had used lower-quality wire for some of the cables. It was too late to replace them, so engineers added 150 extra wires to each cable to make sure the bridge was still strong enough. The last of the main cables' wires were in place by October 1878.

Nearing Completion

After the main cables were in place, workers began adding steel crossbeams to support the roadway. This work started in March 1879. By early 1883, the Brooklyn Bridge was almost finished. Plans for lighting and tolls were approved.

Some groups, like shipbuilders, opposed the bridge's construction. They worried that the bridge would not be high enough for large ships to pass underneath. However, the Supreme Court decided in 1883 that the Brooklyn Bridge was a legal structure.

The Grand Opening

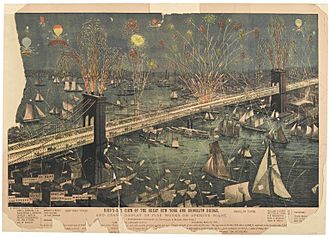

The New York and Brooklyn Bridge officially opened on May 24, 1883. Thousands of people came to the ceremony. Emily Warren Roebling was honored as the first person to cross the bridge. U.S. President Chester A. Arthur and New York Mayor Franklin Edson also attended.

Washington Roebling, still ill, watched the celebrations from his home. There were bands, gun salutes, and fireworks. On the first day, 1,800 vehicles and 150,300 people crossed the bridge. The bridge cost about $15.5 million to build. Around 27 workers died during its construction.

Six days after the opening, a tragic accident occurred on the Brooklyn approach. A woman fell, causing a panic that led to many people being hurt and some losing their lives due to overcrowding. After this, emergency phone boxes and extra railings were added.

To show the bridge was safe, P. T. Barnum, a famous circus master, led a parade of 21 elephants across the bridge on May 17, 1884. This helped calm people's fears about the bridge's strength.

From the 1880s to the 1940s

The Brooklyn Bridge quickly became very popular. Millions of people crossed it each year. In 1898, trolley tracks were added to the roadways. That same year, Brooklyn joined New York City, and the bridge came under city control.

Some safety concerns arose around 1900. In 1901, twelve suspender cables broke, but a full check found no other major problems. After this, inspectors were hired to check the bridge daily. Because of the bridge's popularity, other bridges were planned across the East River. The Williamsburg Bridge opened in 1903, followed by the Queensboro Bridge in 1909 and the Manhattan Bridge in 1909.

In 1911, tolls on the bridge were removed. In 1915, the city officially named it the "Brooklyn Bridge." In 1922, motor vehicles were temporarily banned from the bridge after two cables slipped due to heavy traffic. The ban was lifted in 1925 after new pavement was installed.

Mid- to Late 20th Century Updates

Major Upgrades

The first big upgrade to the Brooklyn Bridge started in 1948. The goal was to rebuild the approach ramps and double the bridge's capacity for cars. This project removed the elevated train and trolley tracks. It also widened each roadway from two to three lanes and added a new steel-and-concrete floor. New ramps were built on both the Brooklyn and Manhattan sides.

During this rebuilding, one roadway was closed at a time, allowing traffic to cross in only one direction. The south roadway was finished in May 1951, and the north roadway in October 1953. The entire renovation, including the promenade, was completed in May 1954. A secret fallout shelter was also built under the Manhattan approach during the Cold War, stocked with emergency supplies.

Repairs and Deterioration

Over time, the Brooklyn Bridge started to show its age and needed more care. By the late 20th century, the number of maintenance workers had greatly decreased. In 1974, heavy vehicles like buses were banned to protect the concrete roadway. By 1980, the bridge was in such poor condition that it faced possible closure.

In June 1981, two diagonal cables snapped, causing a tragic accident. This led the city to speed up plans for a major $153 million renovation. As part of this, the original suspender cables were replaced in 1986. The pedestrian stairs were also updated. In 1982, the bridge was lit up at night to highlight its beauty.

More repairs were needed in the 1990s. In 1993, high levels of lead were found near the towers. In 1999, small pieces of concrete began falling from the bridge. After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the Park Row exit from the bridge was closed for security reasons. In 2003, the bridge's "necklace lights" were turned off to save money but were later turned back on with private donations.

The Brooklyn Bridge in the 21st Century

After a bridge collapse in Minneapolis in 2007, people paid more attention to bridge conditions. The Brooklyn Bridge's approach ramps received a "poor" rating, meaning they needed renovation. In 2010, the NYCDOT began a major renovation project. This included widening ramps, improving earthquake safety, replacing railings, and resurfacing the road. This work caused detours and was completed in 2017.

In 2016, the NYCDOT studied if the bridge could support a wider path for bikes and pedestrians. By then, about 10,000 walkers and 3,500 cyclists used the path daily. In July 2018, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission approved more renovations for the towers and ramps. The federal government provided $25 million for a $337 million rehabilitation project that started in late 2019 and finished in 2023. This included cleaning the granite arches, which revealed their original gray color. Also, 56 new LED lamps were installed on the towers.

In January 2021, the city created a new two-way protected bike path on the Manhattan-bound roadway. This allowed the existing promenade to be used only by pedestrians. The new bike path was completed on September 14, 2021. Despite this, the pedestrian walkway was still often crowded. In January 2024, all street vendors were banned from the bridge. Following the Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse in Maryland in 2024, the National Transportation Safety Board recommended in early 2025 that the Brooklyn Bridge undergo a new safety assessment.

How the Bridge is Used

Car Traffic

Since its opening, the Brooklyn Bridge has allowed horse-drawn carriages and later cars. Originally, each of the two roadways had two narrow lanes. Motor vehicles were banned from July 1922 to May 1925.

After 1950, the main roadway carried six lanes of car traffic, three in each direction. In 2021, a two-way bike lane was added to the Manhattan-bound side, reducing car lanes to five. Because of height and weight limits, large commercial vehicles and buses cannot use the bridge.

On the Brooklyn side, cars can enter from Tillary/Adams Streets and Sands/Pearl Streets, or from exit 28B of the eastbound Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. In Manhattan, cars can enter from the FDR Drive and Park Row, Chambers/Centre Streets, and Pearl Street. The exit to northbound Park Row was closed after the September 11 attacks for security reasons.

Bridge Exits

Vehicles can access the bridge through a series of ramps on both sides. There are also two entrances to the pedestrian path. This system of ramps was built between the mid-1950s and early 1970s.

| County | Location | Mile | Roads intersected | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brooklyn | Brooklyn Heights | 0.0 | 0.0 | Tillary Street / Adams Street south | Pedestrian and bicycle path |

| 0.4 | 0.64 | Northbound entrance only; exit 28B on I-278 | |||

| Southbound exit only; access to I-278 via Old Fulton/Prospect Streets | |||||

| East River | 0.7– 1.0 |

1.1– 1.6 |

Suspension span | ||

| Manhattan | Financial District | 1.2 | 1.9 | Park Row north | Northbound exit only; closed to regular traffic since the September 11 terrorist attacks |

| 1.3 | 2.1 | Northbound exit and southbound entrance; exit 2 on FDR Drive | |||

| 1.4 | 2.3 | Park Row south | Northbound exit and southbound entrance; pedestrian staircase | ||

| 1.5 | 2.4 | Pedestrian and bicycle path | |||

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | |||||

Train and Trolley Traffic

In the past, trains also used the Brooklyn Bridge. Cable cars and elevated trains ran until 1944, and trolleys until 1950.

Cable Cars and Elevated Trains

A cable car service started on September 25, 1883, running on the inner lanes. These cable cars were pulled by a steam-powered system. The service quickly became popular, carrying millions of people each year. Over time, the tracks were changed, and more cars were added.

Later, elevated trains also began to use the bridge. These trains would connect to the cable cars to cross the bridge. New subway lines opened in the early 1900s, offering more ways to cross the river. As a result, the elevated train services on the Brooklyn Bridge slowly declined and stopped completely by 1944.

Trolleys

Trolley service began on the Brooklyn Bridge in 1898, using the middle lanes of the roadways. This service continued until the elevated trains stopped using the bridge in 1944. The trolleys then moved to the protected center tracks. Finally, on March 5, 1950, all streetcar service stopped, and the bridge was used only for cars.

The Pedestrian Walkway

The Brooklyn Bridge has a raised pathway, called a promenade, for people walking and biking. It is in the center of the bridge, 18 feet (5.5 m) above the car lanes. The path is usually 10 to 17 feet (3.0 to 5.2 m) wide. However, some spots, called "pinch points," become narrower because of cables or benches. These spots are popular for taking photos. In 2016, the NYCDOT planned to make the promenade wider.

In 1971, a line was painted to separate cyclists from pedestrians, creating one of the city's first bike lanes. On September 14, 2021, a new, separate bike path was created on the Manhattan-bound roadway. This meant cyclists were no longer allowed on the upper pedestrian path, which is now only for walkers.

You can get onto the pedestrian path from Adams Street in Brooklyn or from Centre Street and Park Row in Manhattan.

Emergency Use

The promenade is very important during emergencies when other ways to cross the East River are not available. During transit strikes in 1980 and 2005, many people walked across the bridge to get to work. Mayors Ed Koch and Michael Bloomberg even joined them. People also walked across after major blackouts in 1965, 1977, and 2003, and after the September 11 attacks.

During the 2003 blackout, many people noticed the bridge swaying. This happened because so many pedestrians were walking at once, and their steps sometimes matched the bridge's natural sway. Engineers noted that the bridge's strong design, with its three support systems, helped it safely handle this movement. John Roebling had designed the bridge to sag but not fall, even if one part of its structure failed.

Bridge Tolls

The Brooklyn Bridge was originally a toll bridge. Carriages and cable car riders paid tolls from the start. By the early 1900s, pedestrians also paid a small fee. However, in July 1911, tolls were removed from all four East River bridges (Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro) as a city policy.

In the early 1970s, the city considered bringing back tolls to help fund public transit and improve air quality. However, this plan was not put into action.

In mid-2023, a plan for congestion pricing in New York City was approved. This means drivers entering Manhattan south of 60th Street now pay a toll. Congestion pricing started in January 2025. Most traffic between the Brooklyn Bridge and the FDR Drive is free from this toll. However, other Manhattan-bound drivers pay a toll that changes depending on the time of day.

Interesting Events and Facts

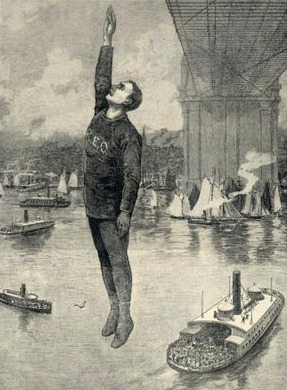

Stunts and Jumps

Many people have tried daring feats on the Brooklyn Bridge. The first person to jump from the bridge was Robert Emmet Odlum on May 19, 1885. He was badly injured and passed away shortly after. Steve Brodie claimed to have jumped from under the bridge in July 1886, though some doubt his story. Larry Donovan made a higher jump a month later.

In 1919, Giorgio Pessi flew a large airplane, the Caproni Ca.5, under the bridge. In 1993, Thierry Devaux illegally performed eight acrobatic bungee jumps near the Brooklyn tower.

Anniversary Celebrations

The bridge's 50th anniversary was celebrated on May 24, 1933, with an airplane show, ships, fireworks, and a banquet. For its 100th anniversary on May 24, 1983, there was a parade of ships, official ceremonies, and a fireworks display. The Brooklyn Museum also showed original drawings from the bridge's construction.

The 125th anniversary was celebrated with a five-day event from May 22–26, 2008. This included a concert, special lighting of the towers, and fireworks. There were also film screenings, walking tours, and other performances.

The Bridge's Impact

When it was built, people were amazed by what technology could do. The bridge became a symbol of hope and progress. It showed how much people believed in their ability to control technology.

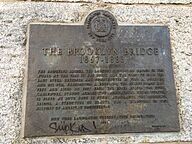

Historical Recognition

The Brooklyn Bridge has been recognized as a National Historic Landmark since 1964. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. It also became a New York City designated landmark in 1967 and a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1972. In 2017, it was even added to UNESCO's list of possible World Heritage Sites.

A bronze plaque on the Manhattan anchorage marks the site of the Samuel Osgood House. This house was built in 1770 and served as the first U.S. presidential mansion.

Cultural Significance

The Brooklyn Bridge has influenced American English. For example, "selling the Brooklyn Bridge" means trying to trick someone with an unbelievable idea. Some con artists in the early 1900s supposedly tried this scam, especially on new immigrants.

As a tourist spot, the bridge is popular for "love locks." Couples write their names and a date on a lock, attach it to the bridge, and throw the key into the water. This is a symbol of their love. However, this practice is against the rules in New York City, and the locks are regularly removed by city workers.

In the 1970s, there was a plan to build a Brooklyn Bridge museum. Although the museum was not built, many original drawings and documents about the bridge were found and are now kept in the New York City Municipal Archives.

In Books, Movies, and Art

The Brooklyn Bridge often appears in movies and TV shows about New York City. It has been featured in many artworks. For example, the 2001 film Kate & Leopold used the bridge as a key part of its story. The bridge is also mentioned in many songs, books, and poems. The American poet Hart Crane used the Brooklyn Bridge as a main idea in his famous poem, The Bridge (1930).

The bridge is also praised for its amazing design. An architecture critic named Montgomery Schuyler wrote a positive review shortly after it opened. He called it "the work which is likely to be our most durable monument." Later critics also saw the Brooklyn Bridge as a work of art, not just an engineering marvel.

The story of the Brooklyn Bridge's construction is told in many places. These include David McCullough's 1972 book The Great Bridge and Ken Burns's 1981 documentary Brooklyn Bridge. It is also featured in the BBC series Seven Wonders of the Industrial World.

See also

In Spanish: Puente de Brooklyn para niños

In Spanish: Puente de Brooklyn para niños

- Brooklyn Bridge Park

- Brooklyn Bridge trolleys

- List of bridges and tunnels in New York City

- List of National Historic Landmarks in New York City

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |