Emily Dickinson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Emily Dickinson

|

|

|---|---|

This daguerreotype (an early photo) taken in 1846 or 1847 is the only real picture of Emily Dickinson after she was a child. It's kept at Amherst College.

|

|

| Born | Emily Elizabeth Dickinson December 10, 1830 Amherst, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | May 15, 1886 (aged 55) Amherst, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet |

| Alma mater | Mount Holyoke Female Seminary |

| Notable works | List of Emily Dickinson poems |

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson (born December 10, 1830 – died May 15, 1886) was a famous American poet.

Emily Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts. Even though her family was well-known in their town, Emily lived most of her life quietly and alone. After studying at the Amherst Academy for seven years, she went to Mount Holyoke Female Seminary for a short time. Then, she returned to her family's home in Amherst. People in town thought she was a bit unusual. She liked to wear white clothes and often didn't want to meet guests. Later in life, she rarely even left her bedroom. Emily never married, and most of her friendships were through letters. She lived a very private life for many years.

Emily wrote nearly 1,800 poems, but fewer than a dozen were published while she was alive. The poems that were published were often changed a lot by publishers. They wanted them to fit the usual poetry rules of that time. Emily Dickinson's poems were special for her era. They often had short lines and usually didn't have titles. She also used slant rhyme (words that almost rhyme) and unusual ways of using capital letters and punctuation. Many of her poems talked about death and what happens after life. These were common topics in her letters to friends.

Most people who knew Emily probably knew she wrote. But it wasn't until after she died in 1886 that her younger sister, Lavinia, found a hidden collection of her poems. That's when the world realized how many amazing poems she had written. Her first book of poems came out in 1890. It was put together by her friends Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd. However, they changed the poems quite a bit. A full collection of her poems, mostly unchanged, was finally published in 1955 by a scholar named Thomas H. Johnson.

Contents

Emily Dickinson's Life Story

Her Family and Early Years

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was born at her family's home in Amherst, Massachusetts, on December 10, 1830. Her family was important in the town, but not super rich. Her father, Edward Dickinson, was a respected lawyer in Amherst. He was also a trustee (a leader) at Amherst College. Emily's ancestors had come to America about 200 years earlier during the Great Migration. They became successful.

Emily Dickinson's grandfather, Samuel Dickinson, helped start Amherst College. In 1813, he built the Homestead, a big house on Main Street. This house became the center of the Dickinson family's life for many years. Samuel Dickinson's oldest son, Edward (Emily's father), was the treasurer of Amherst College for almost 40 years. He also served in the state government and in the United States Congress. On May 6, 1828, he married Emily Norcross. They had three children:

- William Austin (1829–1895), called Austin

- Emily Elizabeth

- Lavinia Norcross (1833–1899), called Lavinia or Vinnie

When Emily was a child, she was described as a very well-behaved girl. Her Aunt Lavinia once said Emily was "perfectly well & contented." She also noted Emily's love for music and her talent at the piano.

Emily went to primary school in a two-story building. Her education was "ambitiously classical," meaning it was very advanced for a girl at that time. Her father wanted his children to be well-educated. He often checked on their schoolwork even when he was away. When Emily was seven, he wrote home, telling his children to "keep school, and learn, so as to tell me, when I come home, how many new things you have learned." Emily always wrote about her father in a kind way. But her letters suggest her mother was often distant and cold. Emily once wrote that she "always ran Home to Awe [Austin] when a child, if anything befell me." She added, "He was an awful Mother, but I liked him better than none."

On September 7, 1840, Emily and her sister Lavinia started at Amherst Academy. This used to be a boys' school but had just started letting girls in. Around the same time, her father bought a new house. Emily's brother Austin later called this big new home the "mansion." He said he and Emily were like "lord and lady" when their parents were out. The house looked out over Amherst's burial ground, which a local minister called "forbidding."

Her Teenage Years

|

They shut me up in Prose – Still! Could themself have peeped – |

| Emily Dickinson, around 1862 |

Emily spent seven years at the Academy. She took classes in English, Latin, science (botany, geology), history, and math. The school's principal, Daniel Taggart Fiske, later said Emily was "very bright" and "an excellent scholar." She missed some school due to illness, but she enjoyed her studies. She wrote to a friend that the Academy was "a very fine school."

From a young age, Emily was worried about death. This was especially true when people close to her died. In April 1844, her cousin and close friend, Sophia Holland, died from typhus. Emily was very upset. Two years later, she wrote that "it seemed to me I should die too if I could not be permitted to watch over her." She became so sad that her parents sent her to stay with family in Boston to get better. Once she felt better, she returned to Amherst Academy. During this time, she met people who would become lifelong friends. These included Abiah Root, Abby Wood, and Susan Huntington Gilbert (who later married Emily's brother Austin).

In 1845, a religious movement happened in Amherst. Many of Emily's friends became very religious. Emily wrote to a friend the next year: "I never enjoyed such perfect peace and happiness as the short time in which I felt I had found my savior." She also said it was her "greatest pleasure to commune alone with the great God." But this feeling didn't last. Emily never officially joined a church. She only went to church regularly for a few years. After she stopped going to church around 1852, she wrote a poem that started: "Some keep the Sabbath going to Church – / I keep it, staying at Home."

In her last year at the Academy, Emily became friends with Leonard Humphrey, the popular new principal. After finishing school on August 10, 1847, Emily started attending Mary Lyon's Mount Holyoke Female Seminary. This school was about ten miles from Amherst. She stayed at the seminary for only ten months. She liked the girls there but didn't make any lasting friendships. There are different ideas about why she left so soon. Maybe she was sick, or her father wanted her home. Perhaps she didn't like the strong religious focus or the strict teachers. Or maybe she was just homesick. Whatever the reason, her brother Austin came on March 25, 1848, to "bring [her] home at all events." Back in Amherst, Emily spent her time helping with household tasks. She enjoyed baking for her family and going to local events in the growing college town.

Early Influences on Her Writing

When Emily was 18, her family became friends with a young lawyer named Benjamin Franklin Newton. Emily wrote after Newton died that he had been "with my Father two years." He was often at their house. While they probably weren't romantically involved, Newton was very important to her. He was the second of several older men (after Humphrey) whom Emily called her "tutor" or "master."

Newton likely introduced her to the poems of William Wordsworth. He also gave her Ralph Waldo Emerson's first book of poems, which greatly inspired her. She later wrote that he "has touched the secret Spring." Newton thought highly of her and believed she was a poet. When he was dying, he wrote to her, saying he wished he could live to see her become the great poet he knew she would be. Many people believe that Emily's statement in 1862—"When a little Girl, I had a friend, who taught me Immortality – but venturing too near, himself – he never returned"—was about Newton.

Emily knew the Bible well and also read popular books of her time. She was probably influenced by Lydia Maria Child's Letters from New York, another gift from Newton. After reading it, she exclaimed, "This then is a book! And there are more of them!" Her brother secretly brought her a copy of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's Kavanagh because her father might not approve. A friend lent her Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre in late 1849. The influence of Jane Eyre is clear: when Emily got her first and only dog, a Newfoundland, she named him "Carlo" after a dog in the book. William Shakespeare was also a huge influence. She wrote to one friend, "Why clasp any hand but this?" and to another, "Why is any other book needed?"

Adulthood and Living Alone

In the 1850s, Emily's closest relationship was with her sister-in-law, Susan Gilbert. Emily sent Susan over 300 letters, more than to anyone else. Susan supported Emily's writing. She was Emily's "most beloved friend, influence, muse, and adviser." Emily sometimes followed Susan's ideas for editing her poems. Susan married Emily's brother Austin in 1856. Their marriage, however, was not a happy one. Emily's father built a house for Austin and Sue called the Evergreens, next to the Homestead.

Until 1855, Emily had not traveled far from Amherst. That spring, she took one of her longest trips with her mother and sister. First, they spent three weeks in Washington, where her father was working in Congress. Then they went to Philadelphia for two weeks to visit family. In Philadelphia, she met Charles Wadsworth, a famous minister. They became strong friends, and their friendship lasted until he died in 1882. Even though she only saw him twice after 1855, she called him "my Philadelphia" and "my dearest earthly friend."

Emily began to withdraw more and more from the outside world. In the summer of 1858, she started creating what would become her lasting work. She reviewed poems she had written and made neat copies, putting them into carefully made manuscript books. She created 40 of these books between 1858 and 1865, holding almost 800 poems. No one knew these books existed until after she died.

The first half of the 1860s was Emily's most productive writing time. This was after she had mostly stopped socializing. Experts today disagree on why Emily became so private. During her life, a doctor said she had "nervous prostration." But some today think she might have had conditions like agoraphobia (fear of open spaces) or epilepsy.

The Woman in White

After her very productive writing period in the early 1860s, Emily wrote fewer poems in 1866. She faced personal losses and also lost her household help. Emily's beloved dog, Carlo, died after 16 years of being her companion. Emily never owned another dog. The family's servant of nine years left that same year. It wasn't until 1869 that a new permanent servant, Margaret Maher, came to replace her. Emily once again had to do chores, including baking, which she was very good at.

|

A solemn thing – it was – I said – |

| Emily Dickinson, around 1861 |

Around this time, Emily's behavior started to change. She did not leave her home unless it was absolutely necessary. As early as 1867, she began talking to visitors from behind a door instead of face-to-face. She became well-known locally for this. She was rarely seen, and when she was, she was usually dressed in white. The only piece of clothing of hers that still exists is a white cotton dress. Few local people who exchanged messages with Emily during her last 15 years ever saw her in person. Austin and his family started protecting Emily's privacy. They decided she should not be talked about with outsiders.

Despite her physical isolation, Emily was still social and expressive through her many notes and letters. When visitors came to her home or her brother's house, she would often leave or send small gifts of poems or flowers. Emily also got along well with children. Mattie Dickinson, Austin and Sue's second child, later said that "Aunt Emily stood for indulgence." MacGregor (Mac) Jenkins, a son of family friends, wrote an article in 1891 called "A Child's Recollection of Emily Dickinson." He remembered her as always supporting the neighborhood children.

In 1868, Higginson asked her to come to Boston so they could meet. She refused, writing: "Could it please your convenience to come so far as Amherst I should be very glad, but I do not cross my Father's ground to any House or town." They finally met when he came to Amherst in 1870. He later described her as "a little plain woman with two smooth bands of reddish hair ... in a very plain & exquisitely clean white piqué & a blue net worsted shawl." He also felt that he was "never with any one who drained my nerve power so much."

Her Later Life

On June 16, 1874, Emily's father, Edward Dickinson, had a stroke and died in Boston. When the simple funeral was held at the Homestead, Emily stayed in her room with the door slightly open. She did not attend the memorial service either. She wrote to Higginson that her father's "Heart was pure and terrible." A year later, on June 15, 1875, Emily's mother also had a stroke. This caused her to be partly paralyzed and to have memory problems. Emily wrote that "Home is so far from Home," showing her sadness about her mother's increasing needs.

|

Though the great Waters sleep, |

| Emily Dickinson, around 1884 |

Otis Phillips Lord, an older judge from Salem, became Emily's friend in 1872 or 1873. After his wife died in 1877, his friendship with Emily likely became a late-life romance. However, their letters were destroyed, so we can only guess. Emily found a close friend in Lord, especially because they shared literary interests. The few letters that survived show many quotes from Shakespeare's plays. In 1880, he gave her a book about Shakespeare's words. Emily wrote that "While others go to Church, I go to mine, for are you not my Church." She called him "My lovely Salem" and they wrote to each other every Sunday. Emily looked forward to this day greatly.

Judge Lord died in March 1884 after being very sick for several years. Emily called him "our latest Lost." Two years before this, on April 1, 1882, Charles Wadsworth, whom Emily called her "Shepherd from 'Little Girl'hood," also died after a long illness.

Her Death

Emily Dickinson died on May 15, 1886, at the age of 55. Her main doctor said she died from Bright's disease, a kidney illness.

Emily was buried in a white coffin. Inside, there were vanilla-scented heliotrope flowers, a Lady's Slipper orchid, and blue violets. The funeral service was simple and short, held in the Homestead's library. Higginson, who had only met her twice, read a poem by Emily Brontë that Emily Dickinson loved. As Emily had wished, her "coffin [was] not driven but carried through fields of buttercups" to be buried in the family plot at West Cemetery.

Emily Dickinson's Published Works

Even though Emily wrote so much, fewer than 12 of her poems were published during her lifetime. After her younger sister Lavinia found almost 1,800 poems, Emily's first book was published four years after her death. Until Thomas H. Johnson published Emily's Complete Poems in 1955, her poems were greatly changed from her original handwritten versions. Since 1890, Emily Dickinson's work has always been available in print.

Poems Published While She Was Alive

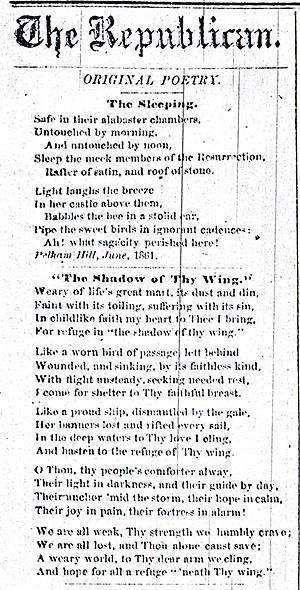

A few of Emily's poems appeared in Samuel Bowles' Springfield Republican newspaper between 1858 and 1868. They were published without her name and were heavily edited. Publishers changed the punctuation and added formal titles. Her first poem, "Nobody knows this little rose," might have been published without her permission. The Republican also published "A narrow Fellow in the Grass" as "The Snake" and "Safe in their Alabaster Chambers –" as "The Sleeping."

In 1864, some poems were changed and published in Drum Beat. This was to raise money for medical care for soldiers in the Civil War. Another poem appeared in April 1864 in the Brooklyn Daily Union.

In the 1870s, Higginson showed Emily's poems to Helen Hunt Jackson. Helen had been at the Academy with Emily when they were girls. Helen was very involved in publishing books. She convinced Emily to publish her poem "Success is counted sweetest" without her name in a book called A Masque of Poets. However, this poem was also changed to fit what people liked at the time. It was the last poem published during Emily Dickinson's life.

Poems Published After Her Death

After Emily died, Lavinia Dickinson kept her promise and burned most of Emily's letters. But Emily had left no instructions about the 40 notebooks and loose papers of poems she had gathered in a locked chest. Lavinia realized how valuable these poems were. She became determined to get them published. She first asked her brother's wife for help, and then Mabel Loomis Todd, her brother's mistress. A disagreement followed, and the poems were split between the Todd and Dickinson families. This stopped a complete collection of Emily's poetry from being published for more than 50 years.

The first book of Emily's Poems, edited by Mabel Loomis Todd and T. W. Higginson, came out in November 1890. Todd said only necessary changes were made. But the poems were actually edited a lot to make the punctuation and capitalization match the style of the late 1800s. Sometimes words were changed to make Emily's meaning less hidden. This first book of 115 poems was a big success. It was reprinted 11 times in two years. Poems: Second Series followed in 1891, and a third series appeared in 1896. One reviewer in 1892 wrote: "The world will not rest satisfied till every scrap of her writings, letters as well as literature, has been published."

Almost a dozen new editions of Emily's poetry were published between 1914 and 1945. These included poems that had not been published before or were newly edited. Martha Dickinson Bianchi, the daughter of Emily's brother Austin and Susan, published collections based on the poems her family had. Mabel Loomis Todd's daughter, Millicent Todd Bingham, published collections based on the poems her mother had. These different versions of Emily's poetry, often with different orders and structures, kept her work in the public eye.

The first scholarly publication came in 1955. It was a complete new three-volume set edited by Thomas H. Johnson. This set became the basis for all future studies of Emily Dickinson. Johnson's goal was to present the poems almost exactly as Emily had left them. They had no titles, were only numbered in a rough time order, and were full of dashes and unusual capitalization. They were also often very hard to understand. Three years later, Johnson also edited and published a complete collection of Emily's letters.

In 1981, The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson was published. This book used clues from the original papers, like smudge marks, to put the poems back in their original order for the first time. Since then, many critics have argued that these small collections of poems have a special meaning when read in their original order.

Emily Dickinson's Poetry Style

Emily Dickinson's poems generally fit into three different time periods. The poems from each period share some common features.

- Before 1861. These poems are often more traditional and emotional. Thomas H. Johnson, who later published her poems, could only date five of Emily's poems before 1858. Two of these are funny, fancy valentines. Two others are typical poems, one about missing her brother Austin. The fifth poem, "I have a Bird in spring," shows her sadness about possibly losing a friendship. She sent it to her friend Sue Gilbert.

- 1861–1865. This was her most creative time. These poems show her strongest and most imaginative work. Johnson estimated she wrote 86 poems in 1861, 366 in 1862, 141 in 1863, and 174 in 1864. He believed that during this time, she fully developed her main ideas about life and death.

- After 1866. It's thought that two-thirds of all her poems were written before this year.

Main Ideas in Her Poems

Emily Dickinson didn't write down her exact artistic goals. Because her poems cover so many different topics, her work doesn't easily fit into just one type of poetry. She has been seen as a Transcendentalist, like Ralph Waldo Emerson (whose poems Emily admired). Besides the main ideas below, Emily's poetry often uses humor, wordplay, and irony.

- Flowers and gardens

- Poems about a "Master" (a mysterious, powerful figure)

- Death and dying

- Religious themes

- Exploring unknown ideas or places

Her Legacy

In the early 1900s, Martha Dickinson Bianchi and Millicent Todd Bingham kept Emily Dickinson's achievements alive. Bianchi promoted Emily's poetry. She inherited the Evergreens house and the rights to her aunt's poems. She published books like Emily Dickinson Face to Face, which made people curious about her aunt. Bianchi's books shared family stories and personal memories about Emily. In contrast, Millicent Todd Bingham took a more factual and realistic approach to the poet.

Emily Dickinson is now seen as a very important and lasting figure in American culture. At first, many people focused on her unusual and private life. But now, she is widely recognized as an innovative, early modern poet. As early as 1891, William Dean Howells wrote that if "nothing else had come out of our life but this strange poetry," America had made a special contribution to world literature through Emily Dickinson. Critic Harold Bloom has placed her among the most important American poets. In 1994, he listed her among the 26 most central writers in Western civilization.

Emily Dickinson's poetry is taught in American literature and poetry classes in the United States, from middle school to college. Her poems are often included in poetry collections. Composers like Aaron Copland have used her poems for songs. Several schools are named after her, for example, Emily Dickinson Elementary Schools in Bozeman, Montana, Redmond, Washington, and New York City. Some literary journals, like The Emily Dickinson Journal, focus on her work. The United States Postal Service issued an 8-cent stamp in her honor on August 28, 1971. A one-woman play called The Belle of Amherst first appeared on Broadway in 1976. It won several awards and was later made into a TV show.

Images for kids

-

Thomas Wentworth Higginson in uniform. He was a colonel in the army from 1862 to 1864.

-

The Dickinson Homestead today, which is now the Emily Dickinson Museum.

See Also

In Spanish: Emily Dickinson para niños

In Spanish: Emily Dickinson para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |