Aaron Copland facts for kids

Aaron Copland (born November 14, 1900 – died December 2, 1990) was an American composer, teacher, writer, and later a conductor. Many people called him "the Dean of American Composers." His music often has open, slowly changing harmonies. This sound reminds many people of the wide-open American landscape and the spirit of pioneers.

Aaron Copland (born November 14, 1900 – died December 2, 1990) was an American composer, teacher, writer, and later a conductor. Many people called him "the Dean of American Composers." His music often has open, slowly changing harmonies. This sound reminds many people of the wide-open American landscape and the spirit of pioneers.

Copland is famous for the music he wrote in the 1930s and 1940s. He wanted this music to be easy for everyone to enjoy. He called it his "everyday" style. Some of his most well-known works from this time include the ballets Appalachian Spring, Billy the Kid, and Rodeo. He also wrote Fanfare for the Common Man and his Third Symphony. Besides ballets and orchestral pieces, he wrote chamber music, songs, opera, and music for movies.

After studying with composer Rubin Goldmark, Copland went to Paris, France. There, he studied with Nadia Boulanger, a famous music teacher. He learned from her for three years. Her wide-ranging approach to music inspired him to have broad tastes too. When he returned to the U.S., Copland wanted to be a full-time composer. He gave talks, wrote music for others, and did some teaching. However, he found that writing modern orchestral music was hard to make money from, especially during the Great Depression.

So, in the mid-1930s, he changed his style to be more accessible. This was like the German idea of "music for use," meaning music that could be both useful and artistic. During the Depression, he traveled a lot to Europe, Africa, and Mexico. He became good friends with Mexican composer Carlos Chávez. It was during this time that he started writing his most famous pieces.

In the late 1940s, Copland became interested in a new way of composing called twelve-tone technique. This method was used by composers like Arnold Schoenberg. Copland started using these techniques in some of his later works, like his Piano Quartet (1950) and Connotations for orchestra (1961). Unlike Schoenberg, Copland used these new ideas to create melodies and harmonies that still sounded like his own style. From the 1960s on, Copland spent more time conducting his own music and the music of other American composers. He often conducted orchestras in the U.S. and the UK and made many recordings.

Contents

Life Story

Growing Up

Aaron Copland was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 14, 1900. He was the youngest of five children in a Jewish family. His father, Harris Morris Copland, had come from Lithuania. The family lived above their shop, H. M. Copland's, which Aaron later called "a kind of neighborhood Macy's." Most of the children helped out in the store. Aaron was not very athletic. He loved to read and often read stories by Horatio Alger on his front steps.

Copland's father was not interested in music. But his mother, Sarah Mittenthal Copland, sang and played the piano. She made sure her children had music lessons. Aaron's older brother, Ralph, was good at the violin. His sister, Laurine, was closest to Aaron. She gave him his first piano lessons and encouraged his musical education. Laurine also loved opera and brought home opera stories for Aaron to read. Copland went to Boys High School. He mostly heard music at Jewish weddings and family gatherings.

Aaron started writing songs when he was about eight years old. His first written music, when he was 11, was for an opera he called Zenatello. From 1913 to 1917, he took piano lessons with Leopold Wolfsohn, who taught him classical music. At 15, after hearing a concert by the famous pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Copland decided to become a composer. At 16, he heard his first symphony. He then took formal lessons in music theory and composition from Rubin Goldmark. Copland studied with Goldmark from 1917 to 1921. Goldmark gave him a strong musical foundation. Copland later said this was "a stroke of luck" because he avoided bad teaching. However, Goldmark didn't like modern music.

Copland's final piece for Goldmark was a piano sonata in a Romantic style. But he also wrote more daring pieces that he didn't show his teacher. He often went to the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Symphony to hear classical music. After high school, Copland played in dance bands. He also took more piano lessons.

Studying in Paris

Copland loved the newest European music. Letters from his friend Aaron Schaffer made him want to go to Paris to study more. An article about a summer music program in France also encouraged him. His father wanted him to go to college, but his mother agreed to let him try Paris. In France, he first studied with Isidor Philipp and Paul Vidal. But Copland found Vidal too similar to Goldmark. A fellow student suggested he switch to Nadia Boulanger, who was 34 years old. He was a bit unsure at first, thinking, "No one to my knowledge had ever before thought of studying with a woman." But she saw his talent right away.

Boulanger taught many students at once and had a strict plan. Copland liked her sharp mind and her ability to find the weak spots in his music. He wrote that she was "not only professor... not only familiar with all music from Bach to Stravinsky, but is prepared for anything worse in the way of dissonance." He also said she was a "charming woman." Copland later wrote that it was "wonderful" to have a teacher with such an open mind. He had planned to stay only one year, but he studied with her for three years. Her varied approach to music inspired his own broad musical tastes.

While studying with Boulanger, Copland also took French language and history classes. He went to plays and visited Shakespeare and Company, a bookstore where many American writers gathered. Paris in the 1920s was full of exciting culture. He traveled to Italy, Austria, and Germany, which added to his musical education. In Paris, Copland also started writing music reviews, which helped him become known in the music world.

1925 to 1935

After his time in Paris, Copland returned to America feeling hopeful. He wanted to be a full-time composer. He rented an apartment in New York City, close to Carnegie Hall. He lived simply and got financial help from two Guggenheim Fellowships. He also earned money from talks, awards, and some teaching and writing. Wealthy supporters also helped him, especially during the Depression. One important supporter was Serge Koussevitzky, the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Koussevitzky was a big fan of "new music" and performed many of Copland's pieces.

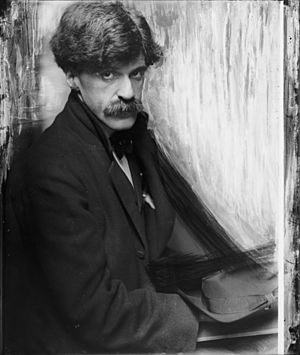

Copland was influenced by photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who believed American artists should show "the ideas of American Democracy." This idea inspired Copland and other artists. Copland looked to jazz and popular music to find an "American" sound. In the 1920s, artists like George Gershwin and Louis Armstrong were popular. By the end of the decade, Copland's music became more abstract. But in the 1930s, when big swing bands became popular, he became interested in jazz again.

Copland also connected with other American composers like Roger Sessions and Virgil Thomson. He became a leader for composers of his generation. He helped create the Copland-Sessions Concerts to show off their music. He was very generous with his time, helping many young American composers. This earned him the title "Dean of American Music."

Because of his studies in Paris, Copland was asked to give talks and write about modern European classical music. He taught classes at The New School for Social Research in New York City. His lectures later became two books: What to Listen for in Music (1937) and Our New Music (1940). He also wrote for The New York Times and other magazines. These articles were later collected in the book Copland on Music.

In the early 1920s, Copland's music was very modern and complex. He thought that only a few people would understand it at first, and that others would learn to like it later. But during the Depression, he realized this approach wasn't working financially. People wanted music that was easier to understand. This led him to create music that could be both useful and artistic, like "music for use." This included music that students could easily learn and music for plays, movies, and radio. Copland also worked with The Group Theatre, which focused on plays about American society. Through this work, he met famous American playwrights.

1935 to 1950

Around 1935, Copland started writing music for young audiences. These works included piano pieces and an opera called The Second Hurricane. During the Depression, Copland traveled a lot, including to Mexico. He became good friends with Mexican composer Carlos Chávez. Copland often returned to Mexico to work and conduct. During his first visit to Mexico, he started writing El Salón México, which he finished in 1936. In this piece and The Second Hurricane, Copland began to use a simpler, more accessible style. This helped him create music that many people would enjoy.

At the same time as The Second Hurricane, Copland wrote "Prairie Journal" for a radio broadcast. This was one of his first pieces to capture the feeling of the American West. This focus on the frontier continued in his ballet Billy the Kid (1938). This ballet, along with El Salón México, became very popular. Copland's ballet music made him known as a true American composer. His music helped American choreographers create new dances and made dance more popular in America. In 1938, Copland helped start the American Composers Alliance to promote American classical music. He was president of this group from 1939 to 1945. In 1939, Copland wrote his first two Hollywood film scores for Of Mice and Men and Our Town.

While these popular works were loved by the public, some critics said Copland was trying too hard to please everyone. One critic warned that Copland was at a "fork in the highroad" leading to either popular or artistic success. Even some of his friends were confused by his simpler style. But Copland said that writing in many different styles was his way of responding to how the Depression affected society and to new media like radio and movies. He believed that a composer who is afraid of losing their artistic honesty by reaching a large audience doesn't understand what art means.

The 1940s were perhaps Copland's most productive years. Some of his works from this time made him famous worldwide. His ballets Rodeo (1942) and Appalachian Spring (1944) were huge successes. His pieces Lincoln Portrait and Fanfare for the Common Man became patriotic favorites. His Third Symphony (1944–1946) became his most famous symphony. The Clarinet Concerto (1948) was written for bandleader and clarinetist Benny Goodman. He ended the 1940s with two film scores: The Heiress and The Red Pony.

In 1949, Copland went back to Europe. He met composers who were using the twelve-tone technique, based on the ideas of Arnold Schoenberg. Copland became interested in using these new methods in his own music.

1950s and 1960s

In 1950, Copland received a scholarship to study in Rome. Around this time, he wrote his Piano Quartet, using Schoenberg's twelve-tone method. He also composed Old American Songs (1950), which became very popular. In 1951–52, Copland gave lectures at Harvard University, which were later published as the book Music and Imagination.

Because of his progressive views, Copland was investigated by the FBI during the "Red Scare" of the 1950s. He was on a list of artists thought to have connections to communism. As a result, A Lincoln Portrait was removed from a concert for President Eisenhower in 1953. Later that year, Copland was questioned by government officials about his travels and groups he was part of. Many musicians were upset by these accusations and showed their support for Copland. The investigations stopped in 1955.

The investigations did not seriously harm Copland's career, though they took up his time and energy. He began to distance himself from certain groups. Copland believed artists should be free to express themselves. He spoke out against the lack of artistic freedom in the Soviet Union.

During this time, some critics also started to dislike the popular style of music that Copland was known for. They thought it was too simple and "dumbed down." They often connected this popular art with new technologies like radio, television, and movies, which Copland wrote music for.

Despite these challenges, Copland traveled widely in the 1950s and early 1960s. He explored new music styles in Europe and heard music by Soviet and Polish composers. He found much of the new electronic music to sound similar and impersonal. He also felt that music made by chance went against his natural instincts as a composer. He said, "I've spent most of my life trying to get the right note in the right place. Just throwing it open to chance seems to go against my natural instincts."

In 1952, Copland was asked to write an opera for television. He had thought about writing an opera since the 1940s. He chose James Agee's Let Us Now Praise Famous Men as his subject. The opera, The Tender Land, premiered in 1954. Some critics found the story weak, but it still became one of the few American operas to be performed regularly.

In 1957, 1958, and 1976, Copland was the Music Director of the Ojai Music Festival in California. For the 100th anniversary of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Copland wrote Ceremonial Fanfare for Brass Ensemble.

Later Years

From the 1960s on, Copland started conducting more and composing less. He felt he was running out of new ideas for music. He became a frequent guest conductor in the United States and the United Kingdom. He also made many recordings of his own music. In 1960, RCA Victor released his recordings of Appalachian Spring and The Tender Land.

From 1960 until his death, Copland lived at Cortlandt Manor, New York. His home, called Rock Hill, became a National Historic Landmark in 2008. Copland's health declined in the 1980s. He passed away on December 2, 1990, from Alzheimer's disease and breathing problems. His ashes were scattered at the Tanglewood Music Center in Massachusetts. Much of his money was used to create the Aaron Copland Fund for Composers, which helps performing groups.

Music Style

Vivian Perlis, who worked with Copland on his autobiography, said that Copland would write down small musical ideas as they came to him. When he needed to compose a piece, he would look at these ideas, which he called his "gold nuggets." If an idea looked promising, he would then write a piano sketch and work on it at the keyboard. The piano was so important to his composing that it influenced his musical style. Copland was sometimes embarrassed that he used the piano so much, until he learned that Igor Stravinsky did the same.

Copland usually didn't decide on the exact instruments for a piece until it was finished. He also didn't always compose from beginning to end. Instead, he would write whole sections in no particular order and then figure out how they would fit together, like putting together a collage. Copland himself said, "I don't compose. I assemble materials." He often used ideas he had written years before. If he had a deadline, like for movie scores, he could work quickly. Otherwise, he preferred to compose slowly. Even with this careful process, Copland believed composing was "the product of the emotions," involving "self-expression" and "self-discovery."

What Influenced Him

When Copland was a teenager, he liked composers like Chopin, Debussy, and Russian composers. But his teacher, Nadia Boulanger, became his most important influence. Copland admired her deep understanding of all classical music. She encouraged him to try new things and to create music that was clear and well-balanced. Following her example, he studied music from all periods and in all forms, from old songs to symphonies. This broad view led Copland to write music for many different settings: orchestra, opera, solo piano, small groups, songs, ballets, theater, and movies. Boulanger especially taught him about "la grande ligne" (the long line), which means having a sense of forward movement and making a piece feel like a complete, flowing whole.

While studying in Paris, Copland was excited by the new French music of composers like Ravel and Satie, as well as a group called Les Six. Composers like Webern and Bartók also impressed him. Copland was always looking for the newest European music. These "modern" composers were breaking old rules and trying new forms, harmonies, and rhythms. They even used jazz and quarter-tone music. Milhaud inspired some of Copland's early "jazzy" works. Copland also admired Arnold Schoenberg's early atonal pieces. Copland called Igor Stravinsky his "hero" and his favorite 20th-century composer. He especially liked Stravinsky's "jagged and uncouth rhythmic effects" and "bold use of dissonance."

Another big influence on Copland's music was jazz. He knew jazz from America, where he listened to it and played it in bands. But he truly understood its power while traveling in Austria. He realized that hearing jazz in a foreign country made it sound new and exciting. He also found that being away from America helped him see his home country more clearly. Starting in 1923, he used "jazzy elements" in his classical music. But by the late 1930s, he moved on to using Latin and American folk tunes in his most successful pieces. Even though his early focus on jazz changed, Copland continued to use jazz in more subtle ways in his later works. From the late 1940s onward, Copland also experimented with Schoenberg's twelve-tone system, which led to two important works: the Piano Quartet (1950) and the Piano Fantasy (1957).

Early Works

Before going to Paris, Copland's compositions were mostly short piano pieces and songs, inspired by Liszt and Debussy. In these, he experimented with unclear beginnings and endings, quick key changes, and using tritones (a specific musical interval). His first published work, The Cat and the Mouse (1920), was a piano piece based on a fable. In Three Moods (1921), the last part is called "Jazzy," which he said "is based on two jazz melodies and ought to make the old professors sit up and take notice."

The Symphony for Organ and Orchestra made Copland known as a serious modern composer. This work used jazz elements to create an "American" sound. It also combined these with modern ideas like unusual scales and dissonant (clashing) harmonies. Copland later felt this work was too "European" and wanted to create a more clearly American style in his future music.

Visits to Europe in 1926 and 1927 showed him the newest music there. In 1927, Copland wrote Poet's Song, his first piece using Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique. This was followed by the Symphonic Ode (1929) and the Piano Variations (1930). Both of these pieces develop a single short musical idea in many ways. This method gave Copland more flexibility and emotional range.

Another important early work is the Short Symphony (1933). In this piece, the jazz-influenced rhythms that were common in Copland's 1920s music are even more present. The music is also much more focused. Music critic Michael Steinberg called the Short Symphony "a remarkable blend of the learned and the everyday," showing a complete picture of the composer in its short 15-minute length. However, after this work, Copland moved towards more accessible music and folk sources.

Popular Works

Copland wrote El Salón México between 1932 and 1936. This piece became very popular, unlike most of his earlier works. He was inspired by visiting a dancehall in Mexico where he saw Mexican nightlife up close. Copland used melodies from Mexican folk tunes, changing their pitches and rhythms. Using folk tunes with variations in a symphonic piece became a pattern he used in many successful works through the 1940s. This also showed his shift to a simpler, more accessible musical language.

El Salón helped Copland prepare to write the ballet Billy the Kid. This ballet became a classic picture of the American West. Based on a novel, with dances by Eugene Loring, Billy was one of the first works to show American music and dance. Copland used six cowboy folk songs to create the right mood. He also used complex rhythms and harmonies to keep the overall tone of the work. In this way, Copland's music was like the murals of Thomas Hart Benton, using elements that a large audience could easily understand. The ballet premiered in New York in 1939, and Copland said he couldn't remember another work of his that was so well-received. Along with the ballet Rodeo, Billy the Kid helped define Copland as a composer of "Americana" and showed a simple form of American nationalism.

Copland's nationalism in his ballets was different from European composers like Béla Bartók, who tried to keep folk tunes as close to the original as possible. Copland made the tunes he used more modern with new rhythms, textures, and structures. He used complex harmonies and rhythms to make folk melodies simpler and more familiar to his listeners. Except for the Shaker tune in Appalachian Spring, Copland often changed the rhythms and note values of traditional melodies. In Billy the Kid, he got many of the simple harmonies from the cowboy tunes themselves.

Like Stravinsky, Copland was skilled at creating a complete and unified piece from different folk-based and original elements. In this way, Copland's popular works like Billy the Kid, Rodeo, and Appalachian Spring are similar to Stravinsky's ballet The Rite of Spring. Within this style, Copland kept the American feeling of these ballets by using "open diatonic sonorities," which create a "pastoral quality" in the music. This is especially clear at the beginning of Appalachian Spring, where the harmonies are "transparent and bare," suggested by the Shaker tune. Variations that contrast with this tune in rhythm, key, texture, and dynamics fit Copland's way of putting together different musical blocks.

Music for Movies

In the 1930s, Hollywood invited classical composers to write music for films, promising better movies and higher pay. Copland saw this as a chance to use his skills and reach a wider audience. Unlike other film scores of the time, Copland's music for movies largely reflected his own style, instead of just copying older Romantic music. He often avoided using a full orchestra. He also didn't use a specific musical theme (leitmotif) for each character. Instead, he matched a theme to the action, without over-emphasizing every moment. Another technique Copland used was to stay silent during quiet, emotional scenes and only start the music as a confirming idea near the end of the scene. Critic Virgil Thomson wrote that the music for Of Mice and Men created "the most distinguished popular musical style yet created in America." Many composers who wrote music for Western movies, especially between 1940 and 1960, were influenced by Copland's style.

Later Works

Copland's work in the late 1940s and 1950s included using Schoenberg's twelve-tone system. He had been interested in this but hadn't fully used it before. He also thought that the lack of clear key in twelve-tone music might prevent him from reaching a wide audience. So, Copland was a bit unsure about it at first. When he was in Europe in 1949, he heard many twelve-tone pieces but didn't like much of it because "individuality was sacrificed to the method." However, the music of French composer Pierre Boulez showed Copland that this technique could be used in a new way, separate from the older, more dramatic style he had associated it with. Hearing later music by Austrian composer Anton Webern and other composers also strengthened this idea.

Copland decided that composing with serial lines was "nothing more than an angle of vision." He felt it was a way to make musical thinking more lively. He started his first serial work, the "Piano Fantasy," in 1951. This piece became one of his most challenging works, and he worked on it until 1957. Critics praised the "Fantasy" when it premiered, calling it "an outstanding addition to his own work and to contemporary piano literature." One critic said, "This is a new Copland to us, an artist advancing with strength and not building on the past alone."

Serialism allowed Copland to combine serial and non-serial methods. Before him, people thought the differences between composers like Schoenberg (who didn't use clear keys) and Stravinsky (who did) were too big to bridge. Copland wrote that serialism pointed in two directions: one towards very organized music with electronic sounds, and the other towards a "very freely interpreted tonalism" (music with clear keys). He chose the latter path. He said that in his Piano Fantasy, he could include "elements able to be associated with the twelve-tone method and also with music tonally conceived." This was different from Schoenberg, who used his tone rows as complete ideas for his compositions. Copland used his rows more like he used ideas in his other pieces, as sources for melodies and harmonies, not as complete, separate parts, except at key moments in the music.

Even after Copland started using twelve-tone techniques, he didn't use them all the time. He went back and forth between music with clear keys and music without. Other later works include: Dance Panels (1959, ballet music), Something Wild (1961, his last film score), Connotations (1962), Emblems (1964, for wind band), Night Thoughts (1972), and Proclamation (1982, his last work).

Critic, Writer, Teacher

Copland didn't see himself as a professional writer. He called his writing "a byproduct of my trade" as "a kind of salesman for contemporary music." He wrote a lot about music, including reviews, analyses of musical trends, and thoughts on his own compositions. He also gave many lectures and performances. Eventually, he collected his notes into three books: What to Listen for in Music (1939), Our New Music (1941), and Music and Imagination (1952). In the 1980s, he worked with Vivian Perlis on a two-volume autobiography, Copland: 1900 Through 1942 (1984) and Copland Since 1943 (1989). These books included Copland's own story and sections from friends and colleagues.

Throughout his career, Copland met and helped hundreds of young composers. They were drawn to him because he was always interested in and understood the modern music scene. He mainly helped these composers outside of formal schools, except for summers at the Berkshire Music Center and some teaching at The New School and Harvard. Copland helped younger composers informally, giving them advice. This advice included focusing on the emotional content of their music rather than just technical details, and on developing their own personal style.

Copland was also willing to critique music that his peers were working on. Composer William Schuman wrote: "As a teacher, Aaron was extraordinary.... Copland would look at your music and try to understand what you were after. He didn't want to turn you into another Aaron Copland.... Everything he said was helpful in making a younger composer realize the potential of a particular work. On the other hand, Aaron could be strongly critical."

Conductor

Although Copland studied conducting in Paris in 1921, he mostly taught himself to conduct. He had his own unique style. Encouraged by Igor Stravinsky, he started conducting his own works during his international travels in the 1940s. By the 1950s, he was also conducting the music of other composers. After a televised appearance where he conducted the New York Philharmonic, Copland became very popular as a conductor. He often featured 20th-century music and lesser-known composers in his programs. Until the 1970s, he rarely planned concerts that only featured his own music. Performers and audiences generally liked his conducting, as it gave them a chance to hear his music as he intended it.

Copland was modest on the podium and copied the style of other composer-conductors like Stravinsky. Critics noted his precision and clarity when leading an orchestra. Observers said he had "none of the typical conductorial vanities." Professional musicians appreciated Copland's simple charm. However, some criticized his "unsteady" beat and "unexciting" interpretations. Koussevitzky even advised him to "stay home and compose." Copland sometimes asked Leonard Bernstein for conducting advice. Bernstein joked that Copland could conduct his works "a little better." Bernstein also noted that Copland improved over time and thought he was a more natural conductor than Stravinsky. Eventually, Copland recorded almost all of his orchestral works with himself conducting.

Legacy

Copland wrote about 100 works in many different styles. Many of his compositions, especially his orchestral pieces, are still performed regularly in America. According to one expert, Copland "had perhaps the most distinctive and identifiable musical voice produced by this country so far." His unique style helped define what American concert music sounds like and greatly influenced many composers who came after him. He combined different influences to create the "Americanism" in his music. Copland himself described the American character of his music as having "the optimistic tone," "his love of rather large canvases," "a certain directness in expression of sentiment," and "a certain songfulness."

Copland's music has become a symbol of America. Conductor Leon Botstein suggests that Copland "helped define the modern understanding of America's ideals, character and sense of place." This means his music played a central role in shaping how Americans see themselves. Composer Ned Rorem said, "Aaron stressed simplicity: Remove, remove, remove what isn't needed.... Thanks to Aaron, American music came into its own."

The music school at Queens College in New York City is named the Aaron Copland School of Music in his honor.

Awards

- On September 14, 1964, Aaron Copland received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon B. Johnson.

- On December 15, 1970, he was given the prestigious University of Pennsylvania Glee Club Award of Merit for his important contributions to music.

- Copland won the New York Music Critics' Circle Award and the Pulitzer Prize in composition for Appalachian Spring.

- His music scores for Of Mice and Men (1939), Our Town (1940), and The North Star (1943) were nominated for Academy Awards. His score for The Heiress won Best Music in 1950.

- In 1961, Aaron Copland received the Edward MacDowell Medal from the MacDowell Colony, where he was a fellow eight times.

- He received Yale University's Sanford Medal.

- In 1986, he was awarded the National Medal of Arts.

- He received a special Congressional Gold Medal from the United States Congress in 1987.

- He was made an honorary member of the Alpha Upsilon chapter of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia in 1961 and received the fraternity's Charles E. Lutton Man of Music Award in 1970.

Selected Works

|

|

Film

- Aaron Copland: A Self-Portrait (1985). A film about Copland.

- Appalachian Spring (1996). A film about the ballet.

- Copland Portrait (1975). A film about Copland.

- Fanfare for America: The Composer Aaron Copland (2001). A film about Copland.

Written Works

- Copland, Aaron (1939; revised 1957), What to Listen for in Music.

- —— (1941; revised 1968), Our New Music (later called The New Music: 1900–1960).

- —— (1953), Music and Imagination.

- —— (1960), Copland on Music.

- —— (2006). Music and Imagination.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Aaron Copland para niños

In Spanish: Aaron Copland para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |