Horatio Alger facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Horatio Alger

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | January 13, 1832 Chelsea, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | July 18, 1899 (aged 67) Natick, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Pen name | Carl Cantab Arthur Hamilton Caroline F. Preston Arthur Lee Putnam Julian Starr |

| Occupation | Author |

| Language | English |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Genre | Children's literature |

| Literary movement | American Realism |

| Notable works | Ragged Dick (1868) |

| Relatives | William R. Alger (cousin) |

| Signature | |

|

|

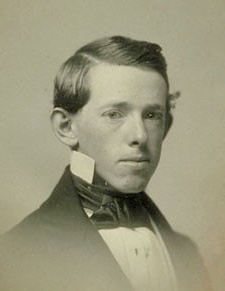

Horatio Alger Jr. (January 13, 1832 – July 18, 1899) was an American author. He wrote many popular books for young people. His stories were often about poor boys who worked hard and became successful. This idea is known as the "rags-to-riches" story. His books were very important in the United States from 1868 until he died in 1899.

Alger became famous in 1868 when he published Ragged Dick. This book was about a poor shoe shiner who worked his way up to a respectable life. It was a huge hit! Many of his later books were similar to Ragged Dick. They often featured characters like:

- a brave, honest, and hardworking young person

- a kind, mysterious stranger

- a snobby young person

- an evil, greedy older person

By the 1870s, Alger's stories started to feel a bit old. His publisher suggested he travel to the Western United States to find new ideas. Alger visited California, but it didn't change his writing much. He kept writing about "poor boys making good." However, his new stories were set in the American West instead of cities in the Northeast.

Contents

Horatio Alger's Life Story

Early Life: 1832–1847

Horatio Alger was born on January 13, 1832. This was in Chelsea, Massachusetts, a town on the coast of New England. His father, Horatio Alger Sr., was a Unitarian minister. His mother was Olive Augusta Fenno.

Alger had family ties to early American settlers. He was a descendant of the Pilgrim Fathers. He also had ancestors who fought in the War of 1812. One ancestor was even part of the group that wrote the U.S. Constitution.

Horatio had siblings named Olive Augusta, James, Annie, and Francis. Horatio was a smart boy. He had poor eyesight (myopia) and breathing problems (asthma). His father decided early on that Horatio would become a minister. So, his father taught him old subjects like Latin and Greek. He also let Horatio see what a minister's job was like.

Alger started Chelsea Grammar School in 1842. But by 1844, his family had money problems. His father moved the family to Marlborough, Massachusetts, for a better job. Horatio attended Gates Academy, a school that prepared students for college. He finished his studies at age 15. He also started publishing his first writings in local newspapers.

College Years and First Books: 1848–1864

In July 1848, Alger passed the entrance exams for Harvard. He joined the class of 1852. Harvard had famous teachers like Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Alger did very well at Harvard. He won many awards for his studies.

In 1849, he became a professional writer. He sold two essays and a poem to a Boston magazine. He loved reading books by authors like Walter Scott and Herman Melville. He also admired Longfellow's poems. Alger graduated with honors in 1852. He was eighth in his class of 88 students.

After college, Alger didn't have a job right away. He went home and kept writing. He sent his work to religious and literary magazines. He briefly attended Harvard Divinity School in 1853. Then he worked as an assistant editor at a newspaper. He didn't like editing, so he quit in 1854. He then taught at a boys' boarding school in Rhode Island.

His first book, Bertha's Christmas Vision, came out in 1856. His second book, Nothing to Do, was a long poem published in 1857. He went back to Harvard Divinity School from 1857 to 1860. After graduating, he traveled around Europe. In 1861, he returned to the United States during the American Civil War. He couldn't join the military for health reasons. But he wrote to support the Union side.

His first novel, Marie Bertrand, was published in parts in a newspaper in 1864. His first book for boys, Frank's Campaign, also came out that year. Alger first wrote for adult magazines. But a friendship with a boys' author, William Taylor Adams, led him to write for young readers.

Becoming a Minister: 1864–1866

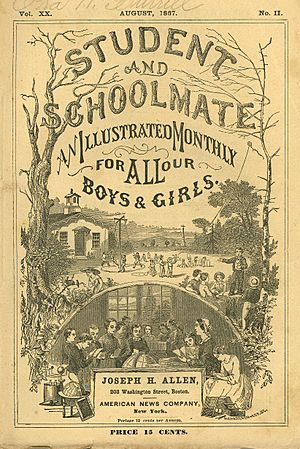

On December 8, 1864, Alger became a pastor. He worked at the First Unitarian Church in Brewster, Massachusetts. Besides his church duties, he organized games for boys. He also led a local group for temperance (avoiding alcohol). He sent stories to The Student and Schoolmate, a magazine for boys. In September 1865, his second boys' book, Paul Prescott's Charge, was published. It received good reviews.

Life in New York City: 1866–1896

In 1866, Alger moved to New York City. He became very interested in the street boys there. He saw that their lives offered many ideas for stories. He decided to focus on writing instead of being a minister. He wrote a poem called "Friar Anselmo." He also became interested in helping the many homeless children in New York after the Civil War.

He attended a church service for children in a poor area called Five Points. This inspired his poem "John Maynard." This poem was about a real shipwreck. It earned him respect from other writers. He published two adult novels that didn't do well. But his stories for boys in Student and Schoolmate and his book Charlie Codman's Cruise were more successful.

In January 1867, the first part of Ragged Dick appeared in Student and Schoolmate. This story was about a poor shoe shiner who became a respectable person. It was a huge success! The story was made into a full novel in 1868. It became his best-selling book. After Ragged Dick, he wrote almost only for boys. He signed a contract to write a Ragged Dick series.

Even with his success, Alger didn't always have a lot of money. He tutored the five sons of a rich banker, Joseph Seligman. He lived in the Seligman home until 1876. In 1875, Alger wrote Shifting for Himself and Sam's Chance. These books showed that his writing ideas were getting old. His book sales went down. So, he traveled West for new ideas, arriving in California in 1877. He returned to New York later that year. He wrote a few more books that were not very exciting. They used his old themes but were set in the West instead of cities.

In New York, Alger kept tutoring rich young people. He also helped boys from the streets. He wrote stories set in both cities and the West. For example, in 1879, he published The District Messenger Boy and The Young Miner. Around 1877, some librarians worried about his books. They tried to remove his works from public libraries. But after he died, interest in his books grew again.

In 1881, Alger informally adopted a street boy named Charlie Davis. In 1883, he adopted another boy, John Downie. They lived in Alger's apartment. In 1881, he wrote a biography of President James A. Garfield. But he added made-up conversations and exciting boyish adventures instead of just facts. The book sold well. He was also asked to write a biography of Abraham Lincoln. Again, he wrote it like a boys' novel, focusing on thrills rather than facts.

In 1882, Alger's father died. Alger continued to write stories about honest boys who outsmarted evil, greedy adults and mean young people. His books were sold in both hardcover and paperback. He lived a busy life, spending time with street boys, old Harvard friends, and rich people. In Massachusetts, he was respected like Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Final Years: 1896–1899

In his last 20 years, the quality of Alger's books went down. His boys' books became simple repeats of his old plots. Times had changed, and boys wanted more exciting stories. His later works even had some violence.

He went to the theater and Harvard reunions. He read literary magazines. He wrote a poem when Longfellow died in 1882. His last novel for adults, The Disagreeable Woman, was published under a fake name. He was happy about the success of the boys he had helped over the years. He stayed interested in helping others. He gave speeches and read parts of Ragged Dick to groups of boys.

His popularity and income decreased in the 1890s. In 1896, he had what he called a "nervous breakdown". He moved permanently to his sister's home in South Natick, Massachusetts.

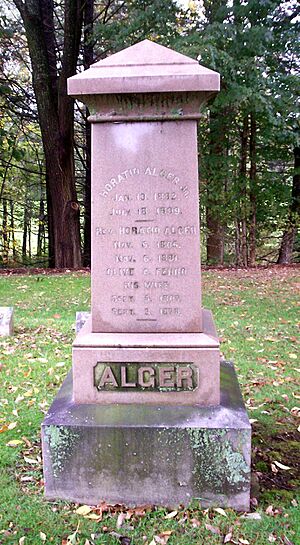

He suffered from bronchitis and asthma for two years. He died on July 18, 1899, at his sister's house. His death was barely noticed at the time. He is buried in the family plot at Glenwood Cemetery in South Natick.

Before he died, Alger asked another writer, Edward Stratemeyer, to finish his unfinished books. In 1901, Young Captain Jack was completed by Stratemeyer. It was promoted as Alger's last work. Alger once said he earned only about $100,000 between 1866 and 1896. When he died, he had little money. He left small amounts to family and friends. He asked his niece, two boys he had adopted, and his sister Olive Augusta to destroy his writings and letters.

After his death, Alger's books became popular again. By 1926, he had sold about 20 million copies in the United States. However, in 1926, people's interest dropped. His main publisher stopped printing his books. Surveys in the 1930s and 1940s showed that very few children had read or even heard of Alger. The first biography about Alger, published in 1928, was later found to be mostly made up.

Horatio Alger's Legacy

Since 1947, the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans has given out an award each year. This award honors "outstanding individuals in our society who have succeeded in the face of adversity." They also give scholarships to "encourage young people to pursue their dreams with determination and perseverance."

In 1982, to celebrate his 150th birthday, the Children's Aid Society held a special event. A musical called Shine! was created in 1982. It was based on Alger's books, especially Ragged Dick.

In 2015, many of Alger's books were re-published as paperbacks and e-books. They were called "Stories of Success" by Horatio Alger. His books were also made into audiobooks.

Horatio Alger's Writing Style and Themes

Horatio Alger's writing style is described as unique. It often included references to famous works like the Bible and William Shakespeare. These references showed how educated Alger was. They also helped make his novels different from simple adventure stories.

There are six main themes in Alger's boys' books:

- Rising to Respectability: This theme is seen in books like Ragged Dick. The poor hero wants to become "respectable." He doesn't get rich, but he finds a comfortable office job.

- Becoming Stronger Through Hardship: In stories like Strong and Steady, rich heroes lose their money. They are forced to learn how to deal with their new, difficult lives. Alger sometimes used young Abraham Lincoln as an example of this theme.

- Inner Beauty vs. Money: This theme became important in Alger's adult books. Characters fall in love and marry based on their good qualities, talents, or intelligence. Money isn't the most important thing. For example, in The Train Boy, a rich girl marries a talented but poor artist.

Most of Alger's novels have similar plots. A boy tries to escape poverty by working hard and living a good life. But it's not always just hard work that saves the boy. Often, a rich older gentleman helps him. This gentleman admires the boy because of a brave or honest act. For example, the boy might save a child from an accident. Or he might find and return the man's lost watch. The older man often takes the boy into his home. He helps the boy find a better job.

Alger's father had money problems when Horatio was a child. His family's property was taken away because of debts. This might be why Alger's books often feature heroes who are in danger of losing their homes. It might also explain why Alger supported ideas like temperance and helping children.

Some people say Alger's stories became darker around 1880. This might be because he was writing Western tales. In these stories, more serious things happened.

One expert says Alger used "formulas" for his stories. These formulas taught lessons. The stories were meant to teach young readers how to act. The idea of a "frontier" (a new, wild place) was important in his stories. Even in city slums, this idea helped create a fairy tale feeling. It showed how a clever hero could be celebrated.

The idea of an "Alger hero" has changed over time. During the 1920s and 1930s, people saw the Alger story as a defense of capitalism. It also offered hope to young people during the Great Depression. But by the 1940s, the Alger hero was seen differently. He was no longer just a poor boy who became respectable through hard work. He was seen as a clever street kid who got rich through quick thinking and luck.

Experts say Alger's themes have become like a "male Cinderella" myth in modern America. Each story has a smart hero, a "fairy godmother" (the rich helper), and challenges. But the American part of this fairy tale is that the hero doesn't become royalty. Instead, he achieves the "American Dream." He gets a respectable middle-class life. This life promises that he can go wherever his hard work takes him.

Horatio Alger's Books

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |