Lydia Maria Child facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lydia Maria Child

|

|

|---|---|

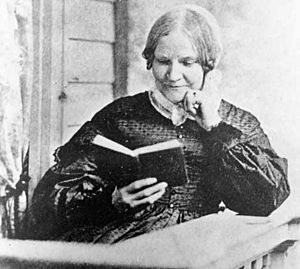

An 1882 engraving of Child

|

|

| Born | Lydia Francis February 11, 1802 Medford, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | October 20, 1880 (aged 78) Wayland, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | North Cemetery Wayland, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Literary movement | Abolitionist, feminism |

| Notable works |

|

| Spouse | |

| Relatives | Convers Francis (brother) |

| Signature | |

Lydia Maria Child (born Francis; February 11, 1802 – October 20, 1880) was an American writer and activist. She fought against slavery and for the rights of women and Native Americans. She also spoke out against America expanding its territories.

Her books and articles were very popular from the 1820s to the 1850s. Sometimes, she surprised her readers by writing about unfair treatment of women and people of color.

Child is perhaps best known for her poem "Over the River and Through the Wood." This poem is about visiting her grandparents' house. That house was restored in 1976 and is in Medford, Massachusetts.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Lydia Maria Francis was born in Medford, Massachusetts, on February 11, 1802. Her parents were Susannah and Convers Francis. She used her middle name, Maria, which she pronounced Ma-RYE-a.

Her older brother, Convers Francis, went to Harvard and became a Unitarian minister. Lydia went to a local school for girls and later to a women's seminary. After her mother died, she lived with her older sister in Maine. There, she studied to become a teacher.

Her brother Convers helped her learn about great writers like Homer and Milton. In her early 20s, she lived with her brother. She met many famous writers and thinkers through him. She also became a Unitarian.

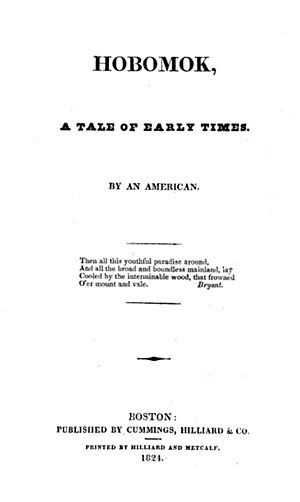

One day, Francis read an article about writing novels based on early New England history. Even though she had never thought of being an author, she immediately started writing her first novel, Hobomok. Her brother liked it, so she finished it in six weeks. It was then published. From that time on, she wrote constantly.

Francis taught school for one year in Medford. In 1824, she opened her own school in Watertown, Massachusetts. In 1826, she started Juvenile Miscellany. This was the first monthly magazine for children in the United States. She managed it for eight years. After she published works against slavery, many of her readers, especially in the South, stopped supporting her. The Juvenile Miscellany closed because book sales and subscriptions dropped.

In 1828, she married David Lee Child and moved to Boston.

Writing Career

Popular Books and Advice

After Hobomok was successful, Child wrote more novels and poetry. She also wrote a guide for mothers called The Mothers Book. But her most popular work was The Frugal Housewife. Dedicated to those who are not ashamed of Economy.

This book mostly had recipes. But it also gave advice to young housewives. For example, it said, "If you are about to furnish a house, do not spend all your money.... Begin humbly." The book was first published in 1829. It was updated and printed 33 times over 25 years. Child said her book was "written for the poor."

In 1832, Child changed the title to The American Frugal Housewife. This was to avoid confusion with a British book called The Frugal Housewife by Susannah Carter. Child felt Carter's book was not right "for the wants of this country."

Fighting for Equality

In 1831, William Lloyd Garrison started his important anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator. Lydia Child and her husband read it and became strong supporters of ending slavery. They also met Garrison in person.

Child was a women's rights activist. She believed that women could not make much progress until slavery was ended. She felt that white women and enslaved people were similar. Both groups were treated unfairly by white men. Child believed that women could achieve more by working with men. She and other women abolitionists pushed for women to have equal roles in the American Anti-Slavery Society. This caused a big disagreement that later split the movement.

In 1833, she published An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans. In this book, she argued that enslaved people should be freed right away. She also said their owners should not be paid for freeing them. She is thought to be the first white woman to write a book supporting this idea.

She looked at slavery from many angles. These included history, politics, money, law, and morals. She wanted to show that freeing enslaved people was possible. She also argued that Africans were just as smart as Europeans. In her book, she wrote that "the intellectual inferiority of the negroes is a common, though most absurd apology, for personal prejudice." This book was the first anti-slavery book printed in America.

Her Appeal got a lot of attention. William Ellery Channing, a famous writer, walked a long way to thank Child for the book. Child faced social disapproval for her views. But from then on, she was seen as a leading fighter against slavery.

Child was a strong supporter of anti-slavery groups. She helped raise money for the first anti-slavery fair in Boston in 1834. This fair was for education and fundraising. It happened every year for decades.

In 1839, Child was chosen for the main committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS). She became the editor of the society's newspaper, National Anti-Slavery Standard, in 1840. While she was editor, Child wrote a weekly column called "Letters from New-York." She later put these letters into a book. Child's editing and her popular column made the National Anti-Slavery Standard one of the most liked anti-slavery newspapers in the U.S. She edited the Standard until 1843. Then her husband took over, and she helped him until May 1844.

While in New York, the Childs became close friends with Isaac T. Hopper. He was a Quaker who worked to end slavery and improve prisons. After leaving New York, the Childs moved to Wayland, Massachusetts. They lived there for the rest of their lives. In Wayland, they gave shelter to enslaved people who were escaping through the Fugitive Slave Law. This law made it harder for enslaved people to gain freedom.

Child was also on the main board of the American Anti-Slavery Society in the 1840s and 1850s. She worked with Lucretia Mott and Maria Weston Chapman.

During this time, she also wrote short stories. These stories explored the difficult issues of slavery. Examples include "The Quadroons" (1842) and "Slavery's Pleasant Homes: A Faithful Sketch" (1843). She wrote anti-slavery stories to reach more people than she could with just essays. The more she wrote about the harsh realities of slavery, the more negative reactions she got from readers. In 1860, she published an anti-slavery essay called The Duty of Disobedience to the Fugitive Slave Act.

Eventually, Child left the National Anti-Slavery Standard. She did not want to support violence as a way to fight slavery. The disagreements among abolitionists made Child feel very distant from the movement. She said she was "finished with the cause forever."

She continued to write for many newspapers and magazines in the 1840s. She also promoted more equality for women. However, because of her bad experience with the AASS, she never again joined organized groups for women's rights or the right to vote. In 1844, Child published the poem "The New-England Boy's Song about Thanksgiving Day." This poem later became famous as the song "Over the River and Through the Wood."

In the 1850s, Child wrote a poem called "The Kansas Emigrants." This was after her friend Charles Sumner, an anti-slavery Senator, was badly beaten in the Senate. Violence broke out in Kansas between people who supported slavery and those who opposed it. This was before the territory voted on whether to become a free or slave state. This violence made Child change her mind about using force. She and Angelina Grimké Weld, who also believed in peace, agreed that violence might be needed to protect anti-slavery settlers in Kansas.

Child also felt sympathy for the radical abolitionist John Brown. She did not approve of his violence, but she greatly admired his bravery and strong beliefs during the raid on Harper's Ferry. She wrote to the Governor of Virginia, Henry A. Wise. She asked for permission to go to Charles Town to nurse Brown. The Governor agreed, but Brown did not accept her offer.

In 1860, Child was asked to write an introduction for Harriet Jacobs's story about being enslaved, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. She met Jacobs and agreed to write the introduction and edit the book.

Native American Rights Work

Child published her first novel, Hobomok, A Tale of Early Times, without her name on it. The story is about a white woman who marries a Native American man. They have a son together. The woman later remarries, and she and her child become part of Puritan society. The idea of marriage between different races caused a scandal at the time. The book was not a big success with critics.

In the 1860s, Child wrote pamphlets about Native American rights. The most important one was An Appeal for the Indians (1868). It asked government officials and religious leaders to bring justice to American Indians. Her writing made Peter Cooper interested in Native American issues. This helped create the U.S. Board of Indian Commissioners. It also led to the Peace Policy during the time of President Ulysses S. Grant.

Personal Life

Lydia Francis taught school until 1828. Then she married Boston lawyer David Lee Child. His work in politics and reform introduced her to social causes like Native American rights and the anti-slavery movement. She was a long-time friend of activist Margaret Fuller. Child often took part in Fuller's "conversations" at Elizabeth Palmer Peabody's bookstore in Boston.

Child died in Wayland, Massachusetts, on October 20, 1880, at age 78. She was buried at North Cemetery in Wayland. At her funeral, abolitionist Wendell Phillips said what many in the anti-slavery movement felt: "We felt that neither fame, nor gain, nor danger, nor calumny had any weight with her."

Legacy

- Child's friend, Harriet Winslow Sewall, organized Child's letters to be published after her death.

- A ship named Lydia M. Child was launched on January 31, 1943. It served during World War II.

- Child was added to the National Women's Hall of Fame in 2007.

Writings

- Hobomok, A Tale of Early Times. 1824

- Evenings in New England: Intended for Juvenile Amusement and Instruction. 1824

- The Rebels, or Boston Before the Revolution (1825). 1850 ed., Google books

- The Juvenile Miscellany, a children's periodical (editor, 1826–1834)

- The First Settlers of New-England:, Or, Conquest of the Pequods, Narragansets and Pokanokets As Related by a Mother to Her Children. 1829.

- The Indian Wife. 1828.

- The Frugal Housewife: Dedicated to Those Who are Not Ashamed of Economy, a book of kitchen, economy and directions (1829; 33rd edition 1855) 1832

- The Mother's Book (1831), an early American instructional book on child rearing, republished in England and Germany

- Coronal. 1931. A collection of verses

- The American Frugal Housewife: Dedicated to those who are not ashamed of Economy (1832) 1841

- The Biographies of Madame de Staël, and Madame Roland. 1832.

- The Ladies' Family Library, a series of biographies (5 vols., 1832–1835)

- Child, Lydia Maria (1833). The Girl's Own Book. https://books.google.com/books?id=gYEEAAAAYAAJ&pg=PR5.

- The Girl's Own Book; new ed. by Mrs. R. Valentine. London: William Tegg, 1863

- An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans 1833

- The Oasis. 1834.

- Philothea. 1836. A romance of Greece set in the days of Pericles

- The Family Nurse. 1837.

- The Liberty Bell. 1842. Includes stories such as The Quadroons

- Slavery's Pleasant Homes: A Faithful Sketch. 1843. a short story

- Letters from New-York, written for the National Anti-Slavery Standard while Child was the editor (2 vols., 1841–1843)

- "The New-England Boy's Song about Thanksgiving Day" (1844), later known by its opening line, "Over the River and Through the Wood". A poem originally published in Flowers for Children, vol. 2. Text of poem

- "Hilda Silfverling: A Fantasy". 1845

- Flowers for Children (3 vols., 1844–1846)

- Fact and Fiction. 1846.

- Rose Marian and the Flower Fairies. 1850.

- The Power of Kindness. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. 1851.

- The Progress of Religious Ideas, Through Successive Ages, an ambitious work, showing great diligence, but containing much that is inaccurate (3 vols., New York, 1855)

- Isaac T. Hopper: A True Life. 1853. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/11859/11859.txt.

- Autumnal Leaves. 1857.

- A Few Scenes from a True History. 1858.

- Child, Lydia Maria (1860). Correspondence between Lydia Maria Child and Gov. Wise and Mrs. Mason, of Virginia. Boston: American Anti-Slavery Society. https://archive.org/details/aberpa.childlm.1860.letters/mode/2up.

- Looking Toward Sunset. 1864.

- The Freedmen's Book. 1865. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/38479.

- A Romance of the Republic. 1867. A novel promoting interracial marriage

- An Appeal for the Indians. 1868.

- Aspirations of the World. 1878.

- A volume of her letters, with an introduction by John G. Whittier and an appendix by Wendell Phillips, was published after her death (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1882)

- Lydia Maria Child: Selected Letters, 1817-1880 (Meltzer, Milton, and Holland, Patricia G., eds.). Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1982

See also

In Spanish: Lydia Maria Child para niños

In Spanish: Lydia Maria Child para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |