Harriet Jacobs facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harriet Jacobs

|

|

|---|---|

Jacobs's only known formal photograph, 1894

|

|

| Born | 1813 Edenton, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | March 7, 1897 (aged 84) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Auburn Cemetery |

| Occupation | Writer, nanny, and relief worker |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Notable works | Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) |

| Children |

|

| Relatives | John S. Jacobs (brother) |

Harriet Jacobs (born 1813 or 1815 – died March 7, 1897) was an African-American writer. She was also an abolitionist, meaning she worked to end slavery. Her amazing life story is told in her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. This book was published in 1861 under the fake name (or pseudonym) Linda Brent. Today, it is known as an important American classic.

Contents

Harriet Jacobs's Life Story

Early Life in Slavery

Harriet Jacobs was born in 1813 in Edenton, North Carolina. Her mother, Delilah Horniblow, was enslaved by a family who owned a local tavern. Because her mother was enslaved, Harriet was also born into slavery. This was a common rule at the time.

Harriet's father, Elijah Knox, was also enslaved. But he was a skilled carpenter and had some special freedoms. He died in 1826. Harriet's mother and grandmother used the Horniblow family name. But Harriet chose the name Jacobs for her children when they were baptized. She and her brother John also used this name after they escaped slavery.

When Harriet was six, her mother died. She then lived with her owner, who was the tavern keeper's daughter. This owner taught Harriet how to sew, read, and write. It was very rare for enslaved people to be able to read or write. North Carolina later made it illegal to teach enslaved people these skills.

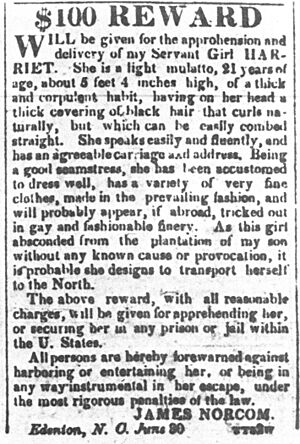

In 1825, Harriet's owner died. She was given to a three-year-old girl named Mary Matilda Norcom. Mary Matilda's father, Dr. James Norcom, became Harriet's real master. Harriet's brother John was bought by Dr. Norcom, so they stayed together.

In 1828, Harriet's uncle Joseph tried to escape. He was caught and sold far away to New Orleans. He later escaped again and reached New York. Harriet and John looked up to him as a hero. They both later named their sons after him.

Seven Years in Hiding

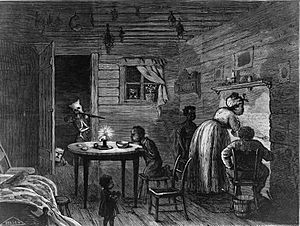

In 1835, Dr. Norcom moved Harriet to his son's plantation. He also threatened to sell her children, Joseph and Louisa, away from her. Harriet decided she had to escape.

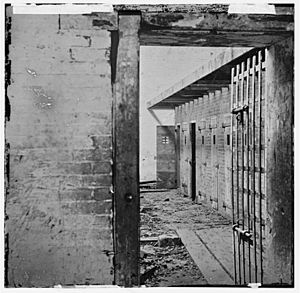

In June 1835, she ran away. A white woman, who also owned enslaved people, bravely hid Harriet in her house. After a short time, Harriet had to hide in a swamp. Finally, she found a tiny space under the roof of her grandmother's house.

This hiding spot was very small, only about 9 feet by 7 feet, and only 3 feet high at its tallest point. Harriet stayed there for seven years! She made small holes in the wall to get fresh air and a little light. This light was just enough for her to sew and read the Bible and newspapers.

Dr. Norcom was very angry. He sold Harriet's children and her brother John to a slave trader. He wanted them sold to a different state to separate them forever. But the trader secretly worked with Samuel Sawyer, the father of Harriet's children. Sawyer bought all three of them, keeping them together.

Sawyer allowed his children, Joseph and Louisa, to live with their great-grandmother, Molly Horniblow. Harriet could often watch her children from her tiny hiding place. In 1838, Sawyer married. Harriet asked her grandmother to remind him of his promise to free their children. He agreed to send their daughter Louisa to Brooklyn, New York, where slavery was already illegal. He also suggested sending their son Joseph to the free states.

Escape to Freedom

In 1842, Harriet finally escaped by boat to Philadelphia. Anti-slavery activists there helped her. She then went to New York City. She found work as a nanny for Imogen, the baby daughter of a famous writer, Nathaniel Parker Willis. This job lasted for many years.

In 1843, Harriet heard that Dr. Norcom was coming to New York to try and force her back into slavery. This was legal in the United States at the time. She quickly went to Boston, where her brother John lived. John had gained his freedom earlier by leaving his master in New York.

Harriet asked her grandmother to send Joseph to Boston to live with his uncle John. After Joseph arrived, Harriet returned to her job as Imogen's nanny. But in October 1843, Norcom found out where she was. Harriet had to flee to Boston again. The strong abolitionist movement in Boston offered her safety. She also brought her daughter Louisa Matilda from Brooklyn to Boston.

In Boston, Harriet took on various jobs. She traveled to England in 1845 as a nanny for Imogen Willis. In England, she noticed there was no racism, which was a big difference from her life in the U.S. This experience helped her feel closer to her Christian faith.

Writing Her Story

Becoming an Author

Harriet's brother, John S. Jacobs, became very involved in the anti-slavery movement. He gave many speeches. In 1849, he managed the Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room in Rochester, New York. Harriet joined him there.

Harriet, who had never been to school, found herself among people who wanted to change America. The Reading Room was in the same building as The North Star, a newspaper run by Frederick Douglass. Douglass and his friends, Amy and Isaac Post, were strong opponents of slavery and racism. They also supported women's suffrage, which meant equal rights for women, including the right to vote.

Gaining Legal Freedom

In 1850, Harriet visited Nathaniel Parker Willis in New York. Willis's second wife, Cornelia Grinnell Willis, asked Harriet to become a nanny for her children again. This was risky because a new law, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, made it easier for slaveholders to recapture escaped enslaved people. Cornelia promised Harriet she would protect her.

In 1852, Harriet read in the newspaper that Dr. Norcom's daughter, her legal owner, was in New York. She planned to reclaim Harriet. Cornelia Willis sent Harriet and her baby daughter, Lilian, to Massachusetts, which was safer.

A few days later, Cornelia wrote to Harriet, saying she wanted to buy Harriet's freedom. Harriet preferred to join her brother in California. But Cornelia bought her freedom anyway for $300. Harriet felt mixed emotions. She was bitter that a person could be "sold" but also very happy that her freedom was finally secure. She felt much "love" and "gratitude" for Cornelia Willis.

Overcoming Challenges to Write

When Harriet met Amy Post in Rochester, Amy was one of the first white people who treated her as an equal. Harriet soon trusted Amy enough to tell her life story. Harriet had kept her experiences secret for a long time. Amy Post later said it was very hard for Harriet to talk about her painful past.

In 1852 or 1853, Amy Post suggested that Harriet write her life story. Harriet's brother had also encouraged her. She felt it was her duty to share her story to help the anti-slavery cause. She wanted to prevent others from suffering as she had.

Harriet agreed to write her story. She wrote a short summary and asked Amy Post to send it to Harriet Beecher Stowe, the famous author of Uncle Tom's Cabin. Harriet hoped Stowe would help her turn it into a book. But Stowe declined, which made Harriet feel betrayed. Harriet then decided to write the book herself.

In June 1853, Harriet read an article defending slavery. It was written by Julia Tyler, the wife of a former president. Harriet spent all night writing a reply. Her letter, signed "A Fugitive Slave," was published in the New York Tribune. This was her first published writing. Her biographer, Jean Fagan Yellin, said, "an author was born."

Harriet wrote her story in her spare time while working as a nanny for the Willis family. She lived at their new country home, Idlewild.

Finding a Publisher

In 1858, Harriet sailed to England to find a publisher. She had good letters of introduction but could not get her book printed. Disappointed, she returned to her job.

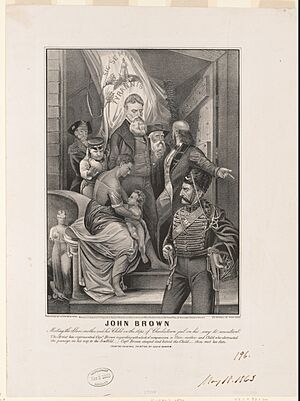

In October 1859, the anti-slavery activist John Brown tried to start a slave rebellion. Many abolitionists, including Harriet, saw him as a hero. Harriet added a tribute to John Brown as the last chapter of her book. She sent her manuscript to publishers in Boston, but they wanted a preface from Nathaniel Parker Willis or Harriet Beecher Stowe. Willis had pro-slavery views, so Harriet didn't want to ask him. Stowe refused. The publishers then went out of business.

Harriet then contacted Thayer and Eldridge, who had published a book about John Brown. They asked for a preface by Lydia Maria Child, another famous writer. Harriet was hesitant after Stowe's refusal, but she tried one last time.

Harriet met Lydia Maria Child in Boston. Child agreed to write a preface and edit the book. Child helped arrange the story in a better order. She also suggested removing the chapter about John Brown and adding more about the violence against Black people after Nat Turner's slave rebellion in 1831.

In January 1861, nearly four years after she finished writing, Harriet Jacobs's Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was finally published. In her book, Harriet changed all the names and places to protect the people involved. She signed the "Preface by the author" as "Linda Brent."

Civil War and Helping Others

Relief Work for Freed People

After Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, many slave states left the United States. This led to the American Civil War. Thousands of African Americans escaped slavery in the South. They were called "Contrabands" and lived in poor camps. Harriet Jacobs felt it was more important to help these people than to become a speaker.

In 1862, Harriet went to Washington, D.C. and Alexandria, Virginia. She saw the terrible conditions of the escaped enslaved people. She wrote a report called Life among the Contrabands, which was published in a newspaper. In it, she described their suffering and asked for donations. She also argued that freed people could build good lives if they got support.

Harriet traveled through the North to gather support for her relief work. The Quakers, a religious group, gave her official papers as a relief agent. From January 1863, she worked in Alexandria. She and another abolitionist, Julia Wilbur, gave out clothes and blankets. They also had to deal with officials who were not helpful or were racist.

Harriet also stayed involved in politics. In May 1863, she attended a meeting in Boston. She watched a parade of the new 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, which was made up of Black soldiers. This was a very important moment, as the government had not wanted Black soldiers before. Harriet wrote that her heart "swelled with the thought that my poor oppressed race were to strike a blow for freedom!"

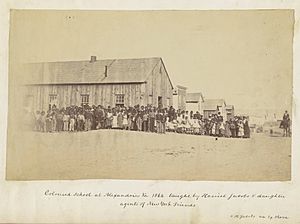

The Jacobs School

In most slave states, teaching enslaved people to read and write was against the law. After Union soldiers took over Alexandria in 1861, some schools for Black people opened. But there were no free schools run by African Americans. Harriet supported a plan by the Black community to start a new school.

In 1863, her daughter Louisa Matilda, who was a trained teacher, came to Alexandria. In January 1864, the Jacobs School opened with Louisa Matilda as its leader. Harriet explained that she wanted the school to be controlled by the Black community. She wanted to help former enslaved people develop "respect for their race."

Harriet's work in Alexandria was recognized by many, especially by abolitionists. She was elected to a women's organization that worked to abolish slavery. In August 1864, she gave a speech to Black soldiers in Alexandria. Many famous abolitionists, like Frederick Douglass, visited her to see her work. Harriet wrote that these six months were the happiest of her life.

Helping Freed People in Savannah

Harriet and Louisa Matilda continued their work in Alexandria until the Civil War ended. They then went to Savannah, Georgia, in November 1865. They helped freed people who had just been freed from slavery. They gave out clothes, opened a school, and planned to start an orphanage and a home for older people.

However, the political situation changed. President Lincoln was killed, and the new president, Andrew Johnson, was from the South. He ordered many freed people to leave the land they had been given. Harriet wrote about these problems and the unfair work contracts forced on former enslaved people.

In July 1866, Harriet and Louisa Matilda left Savannah because of increasing violence against Black people. Harriet then helped Cornelia Willis care for her dying husband.

In 1867, Harriet visited her uncle Mark's widow, the only family member still living in Edenton. Later that year, she traveled to Great Britain to raise money for the orphanage and asylum in Savannah. But when she returned, she realized that the violence from groups like the Ku Klux Klan made these projects impossible. The money she collected was given to a different charity.

During the 1860s, Harriet faced a personal tragedy. Her son Joseph had gone to California and then to Australia with his uncle John. John later returned to England, but Joseph stayed in Australia. Eventually, Harriet stopped receiving letters from Joseph and never heard from him again.

Later Years and Legacy

After returning from England, Harriet Jacobs lived a more private life. She and her daughter Louisa Matilda ran a boarding house in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Some of their boarders were teachers from Harvard University. In 1873, her brother John S. Jacobs returned to the U.S. and lived near them in Cambridge. He died that same year.

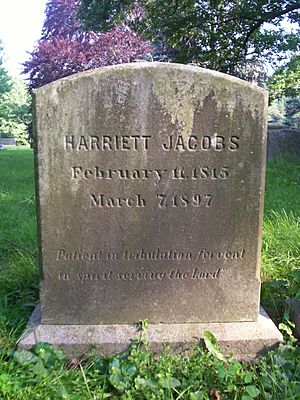

In 1877, Harriet and Louisa moved to Washington, D.C.. Louisa hoped to find work as a teacher. They continued to run a boarding house until Harriet became too sick in 1887. Friends, including Cornelia Willis, helped support them. Harriet Jacobs died on March 7, 1897, in Washington, D.C. She was buried next to her brother at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. Her tombstone reads, "Patient in tribulation, fervent in spirit serving the Lord."

For many years, some historians thought that Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl was a made-up story written by Lydia Maria Child. But in the 1980s, a researcher named Jean Fagan Yellin found many old documents. These documents proved that Harriet Jacobs was the true author and that the book was her real autobiography.

Today, Harriet Jacobs is seen as a symbol of strong female resistance. Her book and Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave are considered the two most important stories written by formerly enslaved people.

The author Colson Whitehead said that Harriet Jacobs was a big inspiration for the main character in his best-selling novel, The Underground Railroad. In his book, the character hides in a small attic space, just like Harriet Jacobs did.

Timeline: Harriet Jacobs and Her Times

| Year | Harriet Jacobs and Her Family | Important Events |

| 1813 | Harriet Jacobs is born. | |

| 1815 | Harriet's brother John S. Jacobs is born. | |

| 1819 | Harriet Jacobs's mother dies. | |

| 1825 | Harriet's owner dies. Harriet becomes the property of Dr. Norcom's young daughter. | |

| 1826 | Harriet's father dies. | |

| 1828 | Harriet's grandmother is bought and set free. | |

| 1829 | Harriet's son Joseph is born. | |

| 1831 | Nat Turner's slave rebellion in Virginia.

William Lloyd Garrison starts his anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator. |

|

| 1833 | Harriet's daughter Louisa Matilda Jacobs is born. | |

| 1834 | Slavery is ended in the British Empire. | |

| 1835 | Harriet Jacobs goes into hiding in her grandmother's attic. | |

| 1838 | Harriet's brother John S. Jacobs gains his freedom. | Frederick Douglass escapes to freedom. |

| 1842 | Harriet Jacobs escapes to the North. She finds work as a nanny in New York. | |

| 1843 | John S. Jacobs returns and settles in Boston. Harriet reunites with her brother and children in Boston. | |

| 1845 | Harriet Jacobs travels to England. | |

| 1848 | Seneca Falls Convention for women's rights. | |

| 1849 | Harriet Jacobs moves to Rochester and becomes friends with Amy Post. | |

| 1850 | Harriet Jacobs is hired again by Cornelia Willis. Her brother John S. goes to California and then Australia. | The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 is passed. |

| 1852 | Cornelia Willis buys Harriet Jacobs's freedom. | Harriet Beecher Stowe writes Uncle Tom's Cabin. |

| 1853 | Harriet begins writing Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. | |

| 1858 | Harriet Jacobs finishes her book and tries to find a publisher in England. | |

| 1859 | John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry. | |

| 1860 | Lydia Maria Child becomes the editor of Incidents. | Abraham Lincoln is elected President. South Carolina leaves the Union. |

| 1861 | Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is published. | The American Civil War begins. |

| 1862 | Harriet Jacobs goes to Washington, D.C., and Alexandria, Virginia, to help escaped enslaved people. | |

| 1863 | Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation frees enslaved people in Confederate states. | |

| 1864 | The Jacobs School opens in Alexandria. | |

| 1865 | Harriet and Louisa Matilda Jacobs go to Savannah, Georgia, to help freed people. | The Civil War ends. The 13th Amendment abolishes slavery. |

| 1867 | Jacobs travels to England to collect money for her projects. | |

| 1868 | Jacobs returns from England and lives a private life. | |

| 1873 | John S. Jacobs returns to the U.S. and dies. | |

| 1897 | Harriet Jacobs dies on March 7, 1897. |

See also

In Spanish: Harriet Jacobs para niños

In Spanish: Harriet Jacobs para niños

- African-American literature

- Olaudah Equiano

- Mary Prince

- Solomon Northup

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |