Mary Prince facts for kids

Mary Prince (born around October 1, 1788 – after 1833) was an important person who fought against slavery. She was born into a slave family in Bermuda. After being sold many times and moved across the Caribbean, she came to England in 1828. There, she bravely left her owner.

Mary Prince could not read or write. But while living in London, she told her life story to Susanna Strickland. Susanna was a young writer who lived with Thomas Pringle. He was a secretary for the Anti-Slavery Society, a group working to end slavery.

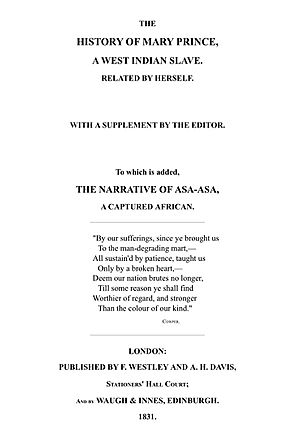

Susanna wrote down Mary's story, which was published as The History of Mary Prince in 1831. This was the first time a black enslaved woman's life story was published in the United Kingdom. Her book described the harsh realities of slavery. It came out when slavery was still legal in Bermuda and the British Caribbean. Her story greatly helped the movement to end slavery in Britain. The book was so popular it was printed three times in its first year.

Contents

Mary Prince's Early Life and Struggles

Mary Prince was born into slavery in Devonshire Parish, Bermuda. Her father, Prince, was a sawyer (someone who cuts wood). He was owned by David Trimmingham. Her mother was a house-servant owned by Charles Myners. Mary had three younger brothers and two sisters, Hannah and Dinah.

When Myners died in 1788, Mary, her mother, and siblings were sold to Captain Darrell. He gave Mary and her mother to his daughter. Mary then became a companion for his young granddaughter, Betsey Williams.

Sold Again and Again

At age 12, Mary was sold for £38 (a lot of money back then) to Captain John Ingham. He lived in Spanish Point. Her two sisters were also sold that same day to different owners. Mary's new owner and his wife were very unkind. Mary and other enslaved people were often severely whipped for small mistakes.

In 1806, Ingham sold Mary to a salt raker on Grand Turk. This island is part of the Turks and Caicos Islands. The owner had salt ponds where salt was collected from seawater. Making salt was a big part of Bermuda's economy. It required a lot of hard work.

Working in Salt Ponds

As a child, Mary worked in terrible conditions in the salt ponds. She stood in water up to her knees. Workers often had to work up to 17 hours straight. Owners worried that if workers left, rain might ruin the salt. Men usually raked the salt. They were exposed to the sun, heat, and the salt itself, which hurt their legs. Women usually did the easier job of packaging the salt.

In 1810, Mary returned to Bermuda with her owner. She said in her story that he treated her very badly. Mary bravely resisted her owner's harsh treatment twice. Once, she defended his daughter, whom he was also beating. The second time, she defended herself when he hit her. After this, she worked for others, earning money for her owner by washing clothes.

In 1815, Mary was sold a fourth time to John Adams Wood of Antigua. She worked in his house as a domestic slave. She cleaned rooms, cared for a young child, and washed clothes. She started to suffer from rheumatism, a condition that made her unable to work. When Adams Wood traveled, Mary earned money for herself. She did laundry and sold coffee, yams, and other goods to ships.

Finding Faith and Love

In Antigua, Mary joined the Moravian Church. She also went to classes there and learned to read. She was baptized in the English church in 1817. In December 1826, Mary married Daniel James. He was a former slave who had bought his freedom. Daniel worked as a carpenter. Mary said that her beatings increased after she got married. Her owners did not want a free black man living on their property.

Journey to England and Fight for Freedom

In 1828, Adams Wood and his family traveled to London. They took Mary Prince with them as a servant. Even though she had worked for them for over ten years, they had many arguments in England. Four times, Wood told her to obey or leave. They gave her a letter that said she could leave but also suggested no one should hire her.

After leaving the Wood household, Mary found help at the Moravian church in Hatton Garden. Within a few weeks, she started working for Thomas Pringle. He was a writer and a leader in the Anti-Slavery Society. This group helped black people in need. Mary also found work with the Forsyth family, but they moved away from England in 1829. The Woods also left England in 1829 and went back to Antigua. Pringle tried to arrange for Wood to free Mary, so she would be legally free.

Fighting for Her Freedom

In 1829, Adams Wood refused to free Mary Prince or let her be bought. This meant that as long as slavery was legal in Antigua, Mary could not go back to her husband and friends without becoming enslaved again. After trying to find a solution, the Anti-Slavery Committee tried to ask Parliament to free Mary, but they did not succeed. At the same time, a new law was suggested to free all enslaved people from the West Indies who had been brought to England by their owners. This law did not pass, but it showed that more and more people wanted to end slavery.

In December 1829, Pringle hired Mary to work in his home. Pringle encouraged Mary to tell her life story. Susanna Strickland wrote it down. Pringle edited the book, and it was published in 1831 as The History of Mary Prince. The book caused a stir because it was the first life story of a black enslaved woman published in Great Britain. At a time when people were strongly campaigning against slavery, her personal story deeply moved many. It sold out three times in its first year.

Two lawsuits happened because of the book, and Mary Prince was asked to speak in court for both.

Mary Prince stayed in England until at least 1833, when she testified in these cases. That year, the Slavery Abolition Act was passed. This law was meant to end slavery in the West Indies by 1840. However, because of protests from formerly enslaved people, the colonies legally ended slavery two years earlier, in 1838.

The History of Mary Prince: A Powerful Story

When Mary Prince's book was published, slavery was still a complicated issue in England. It had not been fully ended by earlier court rulings. Parliament had also not yet ended it in the colonies. There was much uncertainty about what would happen if Britain ended slavery across its empire. The sugar colonies, for example, relied on enslaved labor for their valuable crops.

Mary's book was a personal account. It added to the debate in a way that facts and numbers could not. Her story was direct and real. Its simple but powerful writing was different from the more complex writing styles of the time.

Here is an example of Mary's words about being sold away from her mother when she was young:

It was night when I reached my new home. The house was large, and built at the bottom of a very high hill; but I could not see much of it that night. I saw too much of it afterwards. The stones and the timber were the best things in it; they were not so hard as the hearts of the owners.

Mary Prince wrote about slavery with the authority of her own experience. Her opponents could never match this. She wrote:

I have been a slave myself—I know what slaves feel—I can tell by myself what other slaves feel, and by what they have told me. The man that says slaves be quite happy in slavery—that they don't want to be free—that man is either ignorant or a lying person. I never heard a slave say so. I never heard a Buckra (white) man say so, till I heard tell of it in England.

Her book quickly affected public opinion. It was printed three times in its first year. It also caused arguments. James MacQueen, a newspaper editor, said the book was not accurate. He wrote a long letter in Blackwood's Magazine. MacQueen supported the white West Indian owners and strongly criticized the anti-slavery movement. He said Mary Prince was a "despicable tool" of the anti-slavery group. He claimed they made her speak badly about her "generous and indulgent owners." He also attacked the Pringle family for helping Mary.

In 1833, Pringle sued MacQueen for saying false things about him. Pringle won and received £5. Not long after, John Wood, Mary Prince's owner, sued Pringle. Wood said that Pringle, as the editor of Mary's book, had unfairly described his character. Wood won his case and was given £25. Mary Prince was called to speak in court for both of these trials. Not much is known about her life after this time.

Mary Prince's Lasting Impact

- On October 26, 2007, a special plaque was put up in Bloomsbury, London, where Mary Prince once lived. This was organized by the Nubian Jak Community Trust.

- Also in 2007, the Museum in Docklands opened a new exhibit called London, Sugar & Slavery. It recognizes Mary Prince as an author who "played a crucial role in the abolition campaign."

Mary Prince in Other Media

- Mary Prince is a character in the jazz opera Bridgetower – A Fable of 1807 (2007). This opera is about the 18th-century black violinist George Bridgetower.

- On October 1, 2018, Google Doodle featured Mary Prince to celebrate her 230th birthday. This was shown in the UK, Republic of Ireland, parts of Europe, and South America.

- A podcast version of The History of Mary Prince was created by Jason Young. It was shown as part of Staffordshire Libraries Black History Month in October 2021.

See also

In Spanish: Mary Prince para niños

In Spanish: Mary Prince para niños

- Ottobah Cugoano

- Olaudah Equiano

- Cesar Picton

- Charles Stuart (abolitionist)

- List of slaves

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |