William Lloyd Garrison facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

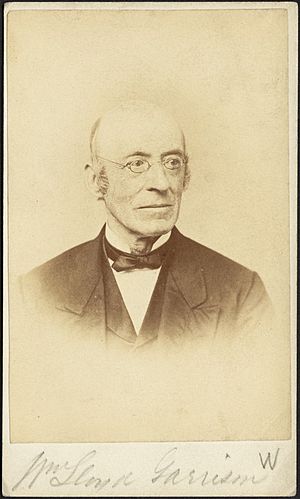

William Lloyd Garrison

|

|

|---|---|

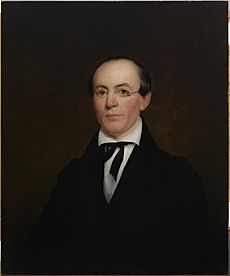

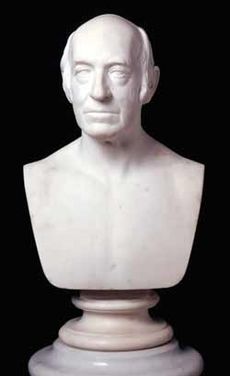

Garrison c. 1870

|

|

| Born | December 10, 1805 |

| Died | May 24, 1879 (aged 73) New York City, U.S.

|

| Occupation | Abolitionist, journalist |

| Known for | Editing The Liberator |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) |

Helen Eliza Benson Garrison

(m. 1834; died 1876) |

| Children | 5 |

| Signature | |

William Lloyd Garrison (December 10, 1805 – May 24, 1879) was an important American abolitionist. An abolitionist is someone who wanted to end slavery. He was also a journalist and a social reformer. He is best known for his newspaper, The Liberator. He started this newspaper in 1831 in Boston. It was published until 1865, when slavery was ended in the United States.

Garrison helped create the American Anti-Slavery Society. He believed that enslaved people should be freed right away, without their owners getting paid. He also supported women's right to vote.

Contents

Early Life and Education

William Lloyd Garrison was born on December 10, 1805, in Newburyport, Massachusetts. His parents were immigrants from a British colony called New Brunswick, which is now part of Canada. His father, Abijah Garrison, left the family in 1808. His mother, Frances Maria Lloyd, was a strong and religious woman. She called her son "Lloyd" to honor her family name.

When he was young, Garrison sold lemonade and candy to help his family. At 13, he started working for the Newburyport Herald newspaper. He learned how to set type for printing. Soon, he began writing articles for the paper, sometimes using the pen name Aristides.

After his training, Garrison became the owner and editor of the Newburyport Free Press. He learned many skills that helped him later as a famous writer and newspaper publisher. In 1828, he became the editor of the National Philanthropist in Boston. This was the first American newspaper to support the temperance movement, which encouraged people to drink less alcohol.

In the 1820s, Garrison became involved in the movement to end slavery. He helped start The Liberator newspaper. In 1832, he helped create the New-England Anti-Slavery Society. This group grew into the American Anti-Slavery Society, which worked to end slavery immediately.

Working for Change

Becoming a Reformer

When he was 25, Garrison joined the movement to end slavery. For a short time, he was part of the American Colonization Society. This group wanted to send free Black people to a territory in Africa, which is now Liberia. However, by 1830, Garrison decided this was wrong. He publicly said he made a mistake and criticized others who supported it. He said his ideas changed because of William J. Watkins, a Black educator who was against colonization.

Writing for Genius of Universal Emancipation

In 1829, Garrison started writing for and became co-editor of the Genius of Universal Emancipation newspaper. This paper was run by Quaker Benjamin Lundy in Baltimore, Maryland. While working there, Garrison became convinced that slavery needed to end right away and completely.

Garrison started a column called "The Black List." It shared short stories about the harshness of slavery. For example, he wrote about a shipper named Francis Todd who was involved in the slave trade. Todd had shipped enslaved people from Baltimore to New Orleans. This was legal at the time, but Garrison wanted to show how cruel it was.

Todd sued Garrison for writing about him. Garrison was found guilty and ordered to pay a fine. He refused to pay and was sent to jail for six months. After seven weeks, a kind person named Arthur Tappan paid his fine, and Garrison was released. Garrison then decided to leave Maryland.

Starting The Liberator Newspaper

In 1831, Garrison went back to New England. There, he and his friend Isaac Knapp started a weekly anti-slavery newspaper called The Liberator.

By 1834, the newspaper had 2,000 readers, and most of them were Black people. The Liberator was sent for free to lawmakers, governors, and even the White House. Garrison believed in ending slavery without violence. However, some people thought he was dangerous because he demanded that slavery end immediately, without paying slave owners. Some Southern states offered a reward of $5,000 (which was a lot of money back then) to capture Garrison.

Isaac Knapp left The Liberator in 1840. The newspaper became very popular in the Northern states. It shared many stories, letters, and news about the abolition movement. It was like a community message board for people who wanted to end slavery. By 1861, people in the North, England, Scotland, and Canada read it. After the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished in 1865, Garrison published the last issue of The Liberator on December 29, 1865.

Leading the American Anti-Slavery Society

Besides publishing The Liberator, Garrison also helped create a new movement to completely end slavery in the United States. In January 1832, he had enough supporters to start the New-England Anti-Slavery Society. By the next summer, this group had many local branches and thousands of members. In December 1833, abolitionists from ten states formed the American Anti-Slavery Society (AAS).

Many women joined and formed their own groups, like the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society. These groups raised money for The Liberator, printed anti-slavery pamphlets, and collected signatures for petitions against slavery.

The American Anti-Slavery Society believed that "Slaveholding is a terrible crime in the eyes of God." They felt it was their duty to end slavery right away. Because of their work, slave owners in both the South and North reacted with anger and violence. Rewards were offered in Southern states to capture Garrison, "dead or alive."

Supporting Women's Rights

Garrison also became a strong supporter of women's rights. This caused some disagreements within the abolitionist movement. In the 1870s, Garrison became a leading voice for the women's right to vote.

He played a big part in the meeting on May 30, 1850, which led to the first National Woman's Rights Convention. He said that the main goal of this new movement should be to get women the right to vote. At the convention in October, Garrison was chosen for the National Woman's Rights Central Committee, which was like the main leadership group for the movement.

After Slavery Ended

After slavery was abolished in the United States, Garrison announced in May 1865 that he would step down as president of the American Anti-Slavery Society. He suggested that the society had achieved its goal and should close.

Even after leaving the AAS and ending The Liberator, Garrison continued to work for social change. He supported civil rights for Black people and women's rights, especially the right to vote. He wrote articles about the Reconstruction period and civil rights for other newspapers.

In 1870, he became an editor for the Woman's Journal, a newspaper about women's right to vote. He also served as president of both the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) and the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association. He was a very important person in the women's right to vote campaigns in New England during the 1870s.

Personal Life

On September 4, 1834, William Lloyd Garrison married Helen Eliza Benson (1811–1876). She was the daughter of an abolitionist merchant. They had five sons and two daughters. Sadly, one son and one daughter died when they were children.

Later Life and Death

In his later years, Garrison spent more time with his family. He wrote weekly letters to his children and cared for his wife, Helen, who was becoming very ill. Helen had a small stroke in 1863 and was mostly confined to their home. She passed away on January 25, 1876, after a cold turned into pneumonia. Garrison was very sad and too ill to attend her funeral.

Garrison slowly recovered from his wife's death. He visited England in 1877, where he met old friends from the British abolitionist movement.

In April 1879, Garrison's health worsened due to kidney disease. He moved to New York to live with his daughter Fanny's family. In late May, his condition became very serious. His five surviving children came to be with him. They sang his favorite hymns, and he tapped his hands and feet to the music. William Lloyd Garrison died on May 24, 1879, just before midnight.

Garrison was buried in the Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston on May 28, 1879. Many people attended his memorial service. Frederick Douglass, a famous abolitionist who had been enslaved, spoke at a service in Washington, D.C. He said that Garrison's greatness was that "he could stand alone with the truth, and calmly await the result."

Garrison's son, William Lloyd Garrison, Jr. (1838–1909), also worked for social change. He supported women's right to vote and other causes. Another son, Wendell Phillips Garrison (1840–1907), was a literary editor. His daughter, Helen Frances Garrison, married Henry Villard. Her son, Oswald Garrison Villard, became a well-known journalist and helped found the NAACP.

Legacy and Memorials

William Lloyd Garrison's ideas influenced many important people. Leo Tolstoy, a famous Russian writer, was greatly inspired by Garrison's writings on Christian anarchism. Tolstoy even wrote a short biography of Garrison. Later, Garrison's work also influenced leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr..

Memorials

- Boston has a memorial to Garrison on Commonwealth Avenue.

- In December 2005, Garrison's family gathered in Boston to celebrate his 200th birthday. They talked about his lasting impact.

- A walking and biking path in Massachusetts was named in honor of Garrison. It opened in 2018.

See also

In Spanish: William Lloyd Garrison para niños

In Spanish: William Lloyd Garrison para niños

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

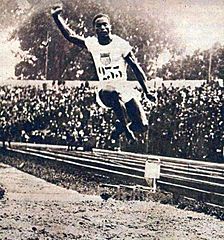

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |