Genius of Universal Emancipation facts for kids

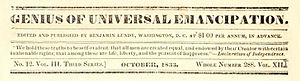

Nameplate from the October 1833 issue

|

|

| Type | Weekly newspaper |

|---|---|

| Founder(s) | Benjamin Lundy |

| Founded | June 1821 |

| Political alignment | Abolitionist |

| Language | English |

| Ceased publication | 1839 |

| City | Mount Pleasant, Ohio, then Greeneville, Tennessee, then Baltimore, Maryland |

| Country | United States |

The Genius of Universal Emancipation was an important newspaper that fought against slavery. It was started by Benjamin Lundy in 1821 in Mount Pleasant, Ohio. This newspaper played a big role in the movement to end slavery in the United States.

Contents

History of the Newspaper

The Genius of Universal Emancipation actually began as another newspaper called The Emancipator in 1820. Benjamin Lundy bought it the next year. Lundy was a Quaker, and his beliefs strongly shaped the newspaper. He believed slavery was wrong for moral and religious reasons. He supported the idea of slowly ending slavery and helping freed slaves move to other countries like Haiti, Canada, or Liberia.

At first, not many people in Ohio read the paper. So, Lundy moved his newspaper to Greeneville, Tennessee. He hoped to share his ideas in a state where slavery was common. The newspaper became popular across twenty-one states. However, slave owners in Tennessee did not like Lundy's ideas.

Lundy realized the newspaper could have a bigger impact on the East Coast. In 1824, he moved The Genius to Baltimore, Maryland. It stayed there for most of its publishing life. Later, the paper moved to Washington and then Philadelphia. Lundy continued to publish it off and on until he passed away in 1839.

Who Was Benjamin Lundy?

Benjamin Lundy was born in 1789 in Sussex County, New Jersey. His parents were Quakers, and they taught him that slavery was wrong from a young age. When he worked as a saddle maker in Wheeling, Virginia, Lundy saw the slave trade for the first time. This experience made him dedicate his life to fighting slavery.

Around that time, the movement to end slavery was losing energy. In 1815, Lundy helped restart it by creating The Union Humane Society. This group wanted to end slavery slowly through new laws. It also aimed to help people who had been freed from slavery. Six years later, Lundy started The Genius newspaper.

Lundy often traveled to give speeches or visit other countries to find places for freed slaves to live. Because of his travels, the paper was sometimes published monthly and sometimes weekly. While he was on a trip to Haiti, Lundy's wife passed away. This left him as a single father to twins. With less time for the newspaper, he asked William Lloyd Garrison to help him edit it.

After Lundy and Garrison stopped working together, Lundy worked with John Quincy Adams. They tried to set up colonies for freed people in Mexico, as Mexico had ended slavery in 1829. However, a conflict in Texas in 1836 stopped these plans. During this time, Lundy hired many assistants to keep the paper going, but it was not published regularly.

He moved the paper to Washington, then to Philadelphia, where it stopped publishing in 1835. In Philadelphia, he started another newspaper called The National Enquirer and Constitutional Advocate for Liberty. This paper also faced money problems and stopped regular publishing. Lundy then moved to Illinois, where his family lived.

He stored his work and belongings in Pennsylvania Hall, a place used for meetings about important topics like slavery. Lundy attended a meeting there, but a mob later burned down Pennsylvania Hall. All of Lundy's work and possessions were destroyed. He moved to Putnam County, Illinois, built a small house and printing shop, and started The Genius again. Sadly, Lundy became very sick and died on August 22, 1839. He passed away with debts and few physical records of his important work.

William Lloyd Garrison's Role

In 1829, Benjamin Lundy invited a young man named William Lloyd Garrison to join him in Baltimore, Maryland. Garrison was a printer and newspaper editor. His skills helped improve the newspaper's look. This allowed Lundy to travel more and give speeches against slavery. Lundy and Garrison first met in Boston during one of Lundy's speaking tours. This meeting was the start of Garrison's career in fighting slavery.

At first, Garrison agreed with Lundy's idea of ending slavery slowly. But over time, Garrison became convinced that slavery needed to end immediately and completely. Even with their different views, Lundy and Garrison continued to work together. They simply signed their articles to show who had written them.

Garrison added a new section to the Genius called "the Black List." This column shared short reports about the cruel parts of slavery, like kidnappings, whippings, and murders. One of Garrison's "Black List" articles reported that a ship owner from his hometown was involved in the slave trade. This ship owner, Francis Todd, had recently moved enslaved people from Baltimore to New Orleans.

Todd sued Garrison and Lundy for libel (printing false information). He filed the lawsuit in Maryland, hoping to get a favorable ruling from courts that supported slavery. The state of Maryland also brought criminal charges against Garrison. He was quickly found guilty and ordered to pay a fine. Lundy's charges were dropped because he had been traveling and was not in charge of the newspaper when the story was printed.

Garrison could not pay the fine and was sentenced to six months in jail. He was released after seven weeks when an anti-slavery supporter named Arthur Tappan paid the fine for him. After this, Garrison decided to leave Baltimore. He and Lundy agreed to go their separate ways. Garrison returned to New England and soon started his own anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator. Garrison would go on to lead the movement to end slavery until the Emancipation Proclamation. Even though they parted ways, Garrison later said about Lundy, "It is to Benjamin Lundy that I owe all that I am as a friend of the slave."

Where to Find Old Copies

You can find old copies of the Genius of Universal Emancipation in different formats, like microfilm or digital versions. These copies are kept in libraries and archives for people to study.

- Genius of Universal Emancipation

- (microfilm);

- Filmed from the New York Public Library (microfiche);

- ProQuest (microfilm);

- Gale (microfiche);

- Gale (online);

- Genius of Universal Emancipation and Baltimore Courier

- ProQuest (online);

- The Genius of Universal Emancipation and Quarterly Anti-Slavery Review (1837–1839)

See also