Pennsylvania Hall (Philadelphia) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pennsylvania Hall |

|

|---|---|

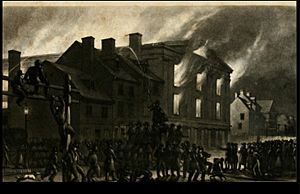

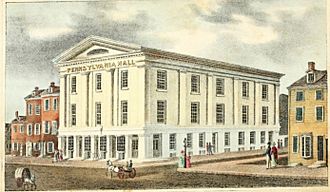

Pennsylvania Hall at its inauguration

(hand colored, artist unknown) |

|

| General information | |

| Status | Destroyed by arson. |

| Address | (1838: "at the south-west corner of Delaware Sixth street and Haines street, between Cherry and Sassafras streets".) |

| Town or city | Philadelphia |

| Country | United States |

| Inaugurated | May 14, 1838 |

| Closed | May 17, 1838 |

| Cost | $40,000 (equivalent to $1,099,250 in 2022) |

| Owner | Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society |

| Height | 42 feet (13 m) |

| Dimensions | |

| Other dimensions | 62 x 100 feet (19 x 30 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 3 + basement |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Thomas Somerville Stewart |

Pennsylvania Hall was a large, beautiful building in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was built in 1837–38 as a place for "free discussion." People could come there to talk about important topics like ending slavery and women's rights.

Just four days after it opened, a mob that was against ending slavery burned it down. This was one of the worst cases of arson in American history at that time. It happened only six months after another anti-slavery supporter, Elijah Parish Lovejoy, was killed by a mob.

These violent acts made the movement to end slavery even stronger. People became more determined to fight for what they believed in. The country became more divided over the issue of slavery.

Contents

Why the Hall Was Built

Pennsylvania Hall was located at 109 N. Sixth Street in Philadelphia. This spot was special because it was near where the Declaration of Independence was signed. It was also in the middle of the Quaker community. Quakers were very active in helping to end slavery and assisting fugitive slaves.

The people who built the Hall were part of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. They needed a place for their meetings because it was hard to find venues that would let them discuss ending slavery.

They decided to name it "Pennsylvania Hall" instead of "Abolition Hall." This was to show that the hall was open to all groups. It could be rented for any purpose that was not "immoral."

Building the Hall

The Hall was designed by architect Thomas Somerville Stewart. It was one of his first big projects.

To pay for the building, a special company was created. About 2,000 people bought shares, each costing $20. This raised over $40,000, which is a lot of money for that time! Other people also gave materials and helped with the work.

Inside Pennsylvania Hall

On the ground floor, there were four shops or offices. One was a reading room and bookstore for anti-slavery materials. Another held the office for the Pennsylvania Freeman, a newspaper that supported ending slavery. The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society also had its office there. The fourth shop sold products made without slave labor.

The first floor also had a "neat lecture room" that could hold 200 to 300 people. There were also committee rooms and wide stairways leading to the second floor.

The second floor had a large auditorium. It had three galleries on the third floor. In total, it could seat about 3,000 people. The building had a special system to bring in fresh air through the roof. It was also lit with gas lamps. The inside looked very fancy. Above the stage, there was a banner with Pennsylvania's state motto: "Virtue, Liberty, and Independence."

In the basement, there was supposed to be a printing press for the anti-slavery newspaper. Luckily, the press had not been moved in yet, so it was saved from the fire.

Plans to Destroy the Hall

Some people knew in advance that the Hall might be destroyed. A letter published in a New York newspaper said that the managers of the building were warned weeks before it was even finished.

The Mayor of Philadelphia also knew there was a group planning to cause trouble. He warned the building owners about the danger. He said that an "organized band" was ready to break up meetings and possibly damage the building.

Timeline of Events

Meetings were held in the Hall even before its official opening on May 14, 1838. Both Black and white people sat together in the audience. Men and women also sat together, except for meetings specifically for women. This was very unusual for Philadelphia at the time. Women and Black people also spoke to these mixed audiences, which some people loved and others saw as a threat.

Monday, May 14, 1838

- In the morning, the Hall officially opened. Important letters were read from people like Gerrit Smith and former President John Quincy Adams. A lawyer named David Paul Brown gave a speech about liberty.

- In the afternoon, a group called the Philadelphia Lyceum held meetings. They discussed topics like education and whether wealth or knowledge had more influence.

- In the evening, there was a lecture about temperance (avoiding alcohol). Someone threw a brick through a window, showing the first sign of trouble.

- That evening, a very important "abolition wedding" took place. Angelina Grimké, a famous anti-slavery speaker, married Theodore Dwight Weld. Many well-known abolitionists attended. Both a Black and a white minister gave blessings.

Tuesday, May 15

- In the morning, the first Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women held a meeting. Women from many states attended, including Lucretia Mott and Sarah Mapps Douglass.

- Later, John Greenleaf Whittier, a famous poet, had a long poem read. Other speakers talked about slavery and the forced removal of Native Americans.

- A crowd started to gather outside the Hall. They posted signs around the city. One sign said that citizens should "forcibly" stop the anti-slavery meetings to protect property (meaning slaves).

Wednesday, May 16

- The Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society held its annual meeting. A large crowd gathered to hear a debate about slavery.

- About 50 to 60 people gathered outside, making threats. This group grew larger throughout the day and used very harsh language. The building managers hired two watchmen to try and keep peace.

- That evening, William Lloyd Garrison introduced Maria Weston Chapman to an audience of 3,000 people. The mob outside became violent. They smashed windows and tried to break into the meeting.

- Despite the chaos, Angelina Grimké Weld gave a powerful hour-long speech. To protect themselves, the white and Black attendees left the building arm-in-arm, through a shower of rocks and insults.

Thursday, May 17

- The Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women met again in the Hall. They refused the Mayor's request to only allow white women at the meeting.

- The building managers asked the Mayor and Sheriff for protection. The Mayor, John Swift, did not seem willing to help. He told them that "public opinion makes mobs" and that most people were against them. He said he would address the crowd but could do nothing more.

- That evening, the managers closed the Hall and gave the keys to the Mayor. He told the crowd to go home and wished them "a hearty good night."

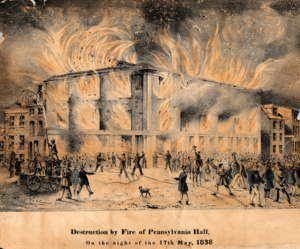

- About 30 minutes later, the mob broke down the doors and set the Hall on fire. There was little help from the police.

- Fire engines arrived, but many firemen did not try to put out the fire in the Hall. They focused on saving the buildings nearby. Some firemen who tried to save the Hall were threatened. When one group tried to spray the Hall, other fire units sprayed water on them instead.

- Many people watched the fire, and some even cheered when the roof fell in.

Friday, May 18 & Saturday, May 19

- After the Hall was burned, the mob attacked other buildings. On Friday, they attacked the Shelter for Colored Children, a charity for Black children.

- On Saturday, they attacked Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church, a church for Black people. The city's Recorder, a police official, had to form a guard of citizens to protect the church.

- The mob also threatened the Philadelphia Ledger newspaper office because it had criticized the mob's actions.

What Happened Next

Newspapers in the Southern states praised the burning of Pennsylvania Hall. Some Northern newspapers that supported slavery blamed the riot on the abolitionists themselves.

Rewards and Arrests

The Mayor of Philadelphia offered a $2,000 reward, and the Governor of Pennsylvania offered $500 for information leading to arrests. Some people were arrested, but no one was ever found guilty. The rewards were never claimed.

Investigation of the Mayor

Mayor John Swift received a lot of criticism. People said he did not do enough to stop the mob. The city's official report blamed the fire on the abolitionists, saying they had upset citizens by encouraging "race mixing" and violence.

The Sheriff of Philadelphia County, John G. Watmough, reported that he tried to arrest rioters himself. But they were either taken from him or let go by others. He said no one helped him.

Trying to Rebuild

After the fire, a new fund was started to raise $50,000 to rebuild the Hall. However, the building was never rebuilt.

Getting Money for Damages

Because the Hall was destroyed by a mob, the city was responsible for the damages. After many years, the Anti-Slavery Society was able to get some money back from the city for their losses.

Impact on the Nation

The destruction of Pennsylvania Hall was a major event. It helped many people in the North realize how serious the issue of slavery was. This awakening was important in the fight to end slavery.

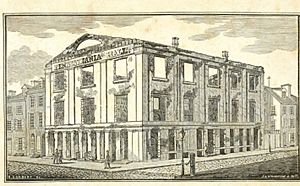

The burned-out shell of the Hall stood for several years. It became a place where abolitionists would visit. Many believed that the fire, instead of stopping the movement, had actually made it stronger.

Historical Marker

In 1992, a historical marker was placed at the site of Pennsylvania Hall. It says: "Built on this site in 1838 by the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society as a meeting place for abolitionists, this hall was burned to the ground by anti-Black rioters three days after it was first opened."

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |