Walter Pater facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Walter Pater

|

|

|---|---|

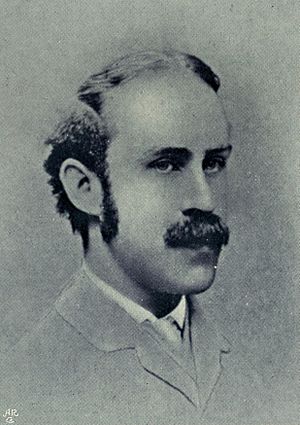

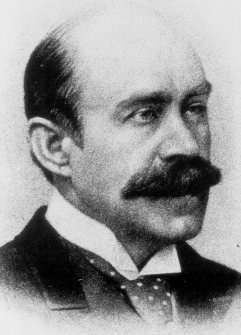

Pater in the 1890s (photograph by Elliott & Fry)

|

|

| Born | 4 August 1839 Stepney, London, Middlesex, England |

| Died | 30 July 1894 (aged 54) Oxford, England |

| Resting place | Holywell Cemetery |

| Occupation | Academic, essayist, writer |

| Language | English |

| Alma mater | The Queen's College, Oxford |

| Genre | Essay, art criticism, literary criticism, literary fiction |

| Notable works | The Renaissance (1873), Marius the Epicurean (1885) |

| Notable awards | Honorary LL.D, University of Glasgow (1894) |

Walter Horatio Pater (born August 4, 1839 – died July 30, 1894) was an English writer. He was known for his essays, art reviews, and stories. Many people thought he was one of the best writers of his time. His first and most famous book was Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873). In this book, he shared his ideas about art. He also talked about living a rich inner life. Many saw his book as a key text for the Aestheticism movement.

Contents

Walter Pater's Early Life

Walter Pater was born in Stepney, a part of London. His father, Richard Glode Pater, was a doctor who helped the poor. Walter's father died when he was a baby. His family then moved to Enfield. Walter went to Enfield Grammar School. The headmaster also taught him privately.

School Days and Discoveries

In 1853, Walter went to The King's School, Canterbury. The beautiful cathedral there deeply impressed him. This feeling stayed with him his whole life. His mother, Maria Pater, died in 1854 when he was 14. As a schoolboy, Pater read Modern Painters by John Ruskin. This book made him love art and appreciate good writing. In 1858, he won a scholarship to Queen's College, Oxford.

University Years

At Oxford, Pater loved to read widely. He was interested in literature and philosophy beyond his schoolwork. He enjoyed writers like Flaubert and Baudelaire. He visited his aunt and sisters in Heidelberg, Germany. There he learned German and read German philosophers. A scholar named Benjamin Jowett saw his talent. Jowett offered to teach him extra lessons. However, Pater did not do as well as expected in Jowett's classes. He earned a lower degree in 1862.

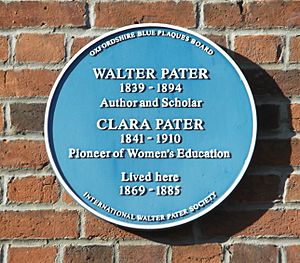

As a boy, Pater thought about becoming a priest. But at Oxford, his Christian faith weakened. He liked the beauty and rituals of the church. Yet, he was not interested in its teachings. So, he did not become a priest. After graduating, Pater stayed in Oxford. He taught private students about Classics and Philosophy. His sister Clara Pater later taught Greek and Latin. She was also a founder of Somerville College. In 1864, Pater became a fellow at Brasenose. He was chosen because he could teach modern German philosophy. This started his career at the university.

Pater's Career and Writings

Pater had many chances to study and teach more at Oxford. He also traveled to Europe, visiting Florence, Pisa, and Ravenna in 1865. These trips made him even more interested in art and literature. He began to write articles and reviews. His first published essay was about Coleridge in 1866. It was called 'Coleridge's Writings'.

A few months later, his essay on Winckelmann appeared. This showed his early ideas about art. Then came 'The Poems of William Morris' (1868). This essay showed his love for romantic writing. In the next years, he wrote about Leonardo da Vinci (1869), Sandro Botticelli (1870), and Michelangelo (1871).

The Renaissance Book

These essays, and others, were put together in his book Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873). Later, it was renamed The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry. The essay on Leonardo includes his famous thoughts on the Mona Lisa. His Botticelli essay was the first in English about that painter. It helped bring new interest to Botticelli. The Winckelmann essay explored a person Pater felt close to.

An essay on 'The School of Giorgione' was added later. It contains Pater's famous saying: "All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music." This means that art tries to make its message and form one, like music does. The final parts of his 1868 William Morris essay became the book's 'Conclusion'.

The Controversial Conclusion

This short 'Conclusion' became Pater's most important and debated writing. It suggested that our lives are made of constant changes. Our minds are full of fleeting thoughts and feelings. These are "unstable, flickering, inconstant" and unique to each person. He wrote that everything is always changing.

Pater believed we should "get as many pulsations as possible into the given time." This means living intensely and experiencing life fully. He said, "To burn always with this hard, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life." He felt that forming habits was a failure. Habits make us live in a routine way. He encouraged people to seek out "any exquisite passion" or new knowledge. He also suggested finding joy in art and senses. This "quickened, multiplied consciousness" helps us deal with life's constant changes.

The Renaissance was seen by some as promoting a carefree, pleasure-seeking lifestyle. This led to criticism from traditional thinkers. Even his former teacher and a bishop disapproved. Some critics called it "poisonous" and "false."

In 1874, Pater was not given a promised university position. This was partly due to the controversy. Around this time, letters showed a close friendship with a young student. This student had caused trouble for being openly gay. Many of Pater's works talk about male beauty and friendship.

In 1876, a writer named Mallock made fun of Pater in a book. This satire appeared when Pater was considered for a poetry professorship. It helped convince Pater to withdraw his name.

Marius the Epicurean and Imaginary Portraits

Pater became well-known in Oxford and London. He tutored Gerard Manley Hopkins and was friends with him. He also met other writers and artists like Oscar Wilde and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. He supported the young artist Simeon Solomon. Pater realized his 'Conclusion' could be misunderstood. So, he removed it from the second edition of Renaissance in 1877. He put it back later with small changes in 1888. He then decided to explain his ideas better through stories.

In 1878, he published 'Imaginary Portraits 1. The Child in the House'. This was a semi-autobiographical story about his childhood. It showed his unique writing style. This was the first of many "Imaginary Portraits." Pater basically invented this type of writing. These stories were not about plots or dialogue. Instead, they were deep studies of made-up characters in historical settings. They often explored new ideas or feelings. Many were hidden self-portraits, looking into his own thoughts.

Pater planned a big new work. He stopped his teaching duties in 1882. He kept his college rooms and visited Rome for research. In 1885, he published his philosophical novel Marius the Epicurean. This long "imaginary portrait" was set in ancient Rome. Pater felt that ancient Rome was similar to his own time. The story follows a young Roman named Marius. Marius tries to live an "aesthetic" life, based on sensation and perception. He leaves his childhood religion and tries different philosophies. He even becomes secretary to the emperor Marcus Aurelius. Marius tests Pater's idea that seeking sensation and insight can be stimulating. The novel shows Pater's longing for the feeling of religious faith he had lost. Marius was well-received and sold well. Pater made many style changes for the third edition in 1892.

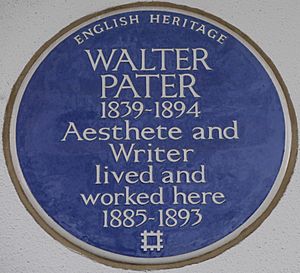

In 1885, Pater was considered for a professorship at Oxford. But he withdrew because of ongoing criticism. After this, he moved to London with his sisters in 1885. He lived there until 1893.

From 1885 to 1887, Pater published four new imaginary portraits. These were studies of characters who felt out of place in their time. They often brought trouble upon themselves. These stories were collected in Imaginary Portraits (1887). In these, Pater explored the struggles between old and new ideas. He also looked at the balance between thinking and feeling. He warned against going to extremes in ideas, art, or senses.

Later Works and Death

In 1889, Pater published Appreciations, with an Essay on Style. This book was a collection of his essays on literature. It was well-liked. The essay 'Style' explained his beliefs about writing. It ended with the idea that a writer's style is personal yet also universal. The book also included essays on Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Thomas Browne.

In 1893, Pater and his sisters moved back to Oxford. He was now a popular lecturer. That year, his book Plato and Platonism was published. In this book, Pater connected Greek culture to his ideas about romanticism and classicism. He saw two opposing forces in Greek history. One was about imagination and change. The other was about simplicity and order.

In early 1894, 'The Child in the House' was published as a small book. It sold out very quickly.

On July 30, 1894, Walter Pater died suddenly at his Oxford home. He was 54 years old. He was buried in Holywell Cemetery, Oxford.

Posthumous Publications

After Pater's death, his friend Charles L. Shadwell collected and published more of his works. In 1895, Greek Studies was published. This book included essays on Greek myths, religion, and art. It contained 'Hippolytus Veiled', a beautiful piece about the boyhood of Hippolytus. This story showed Pater's love for simple beauty.

In the same year, Shadwell published Miscellaneous Studies. This book included 'The Child in the House' and other self-revealing "Imaginary Portraits." These stories explored the idea of ancient gods appearing in Christian times. It also included Pater's last unfinished essay on Pascal.

In 1896, Shadwell edited and published seven chapters of Pater's unfinished novel Gaston de Latour. This novel was set in 16th-century France. Pater had planned it as the second part of a series of novels.

Other collections of his essays and reviews were published later. His complete works were issued in 1901 and reissued in 1910.

Walter Pater's Influence

Toward the end of his life, Pater's writings became very influential. His ideas helped shape the Aesthetic Movement. Oscar Wilde, a leading figure in this movement, greatly admired Pater. Wilde even mentioned him in his own writings.

Pater also influenced many art critics and early modern writers. These included Marcel Proust, James Joyce, and W. B. Yeats. His ideas can be seen in the "stream-of-consciousness" novels of the early 20th century. In literary criticism, Pater's focus on personal experience helped change how literature was studied. Many readers found inspiration in his call to "burn always with this hard, gem-like flame." They liked his idea of seeking the "highest quality" in every moment.

How Pater Wrote and Thought

Pater's way of writing and thinking was special. He explained his method in the 'Preface' to The Renaissance. He believed that when we look at art or ideas, we should first understand our own feelings about them. He asked, "What is this song or picture... to me?" After understanding our feelings, we then look for the "power or forces" that created them. Pater was very interested in the original personalities and minds behind the art.

Pater's Writing Style

Pater was highly praised for his writing style. He worked very hard to make his prose beautiful. He would write ideas on small pieces of paper and arrange them carefully. A friend, Edmund Gosse, said writing was "travail and an agony" for Pater. He wrote on ruled paper, leaving every other line blank. This allowed him to add changes and corrections. He would even print drafts to see how they looked.

Pater focused on crafting perfect sentences and paragraphs. His writing often had pauses and small side thoughts. This gave his prose a unique, thoughtful flow. A. C. Benson called Pater's style "absolutely distinctive and entirely new." He felt it appealed more to writers than to regular readers. G. K. Chesterton described Pater's prose as calm and deep. He said it showed a "vast attempt at impartiality."

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Walter Pater para niños

In Spanish: Walter Pater para niños

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |