George Eliot facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Eliot

|

|

|---|---|

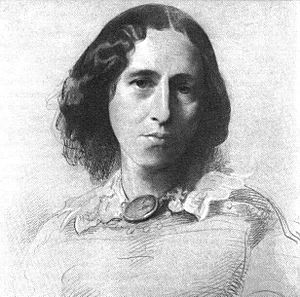

Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) in 1850

|

|

| Born | Mary Anne Evans 22 November 1819 Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England |

| Died | 22 December 1880 (aged 61) Chelsea, London, England |

| Resting place | Highgate Cemetery (East), Highgate, London |

| Pen name | George Eliot |

| Occupation | Novelist, poet, journalist, translator |

| Period | Victorian |

| Notable works | Scenes of Clerical Life (1858) Adam Bede (1859) The Mill on the Floss (1860) Silas Marner (1861) Romola (1862–1863) Felix Holt, the Radical (1866) Middlemarch (1871–72) Daniel Deronda (1876) |

| Spouse |

John Cross

(m. 1880) |

| Partner | George Henry Lewes (1854–1878) |

Mary Ann Evans (born November 22, 1819 – died December 22, 1880) was a famous English writer. She is best known by her pen name, George Eliot. She was a novelist, poet, journalist, and translator. She was one of the most important writers of the Victorian era.

George Eliot wrote seven novels. These include Adam Bede (1859), The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), and Middlemarch (1871–72). Many of her stories are set in the English countryside. She was known for making her stories feel very real. She also explored the inner thoughts and feelings of her characters.

Her novel Middlemarch is often called one of the greatest novels ever written in the English language.

Contents

Life

Growing Up and School

Mary Ann Evans was born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England. She was the third child of Robert and Christiana Evans. Her father managed a large estate called Arbury Hall. Mary Ann was born on this estate. Later, her family moved to a house called Griff House.

From a young age, Mary Ann loved to read. She was very smart. Because she wasn't seen as traditionally beautiful, her family thought she might not marry. This led her father to give her a good education. This was unusual for girls at that time.

She went to several schools between the ages of five and sixteen. At school, she was taught by teachers who had strong religious beliefs. After age sixteen, she mostly taught herself. She had access to the library at Arbury Hall. This helped her learn a lot about many subjects. Her studies in classic literature, like Greek stories, influenced her writing. She also saw the differences between the rich landowners and the poorer people on the estate. These differences appeared in her books.

Moving to Coventry

In 1836, Mary Ann's mother died. Mary Ann, who was 16, returned home to take care of the house. When she was 21, her brother took over the family home. So, Mary Ann and her father moved to Foleshill near Coventry.

In Coventry, she met Charles and Cara Bray. They were wealthy and used their money to help others. The Brays had a home where people with new and different ideas would meet and talk. Mary Ann became good friends with them. Through this group, she learned about more open ways of thinking about religion. She read books by writers like David Strauss and Ludwig Feuerbach. These writers questioned the literal truth of the Bible.

Mary Ann's first big writing project was translating Strauss's book, The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined, into English in 1846. This book caused a stir because it suggested that the miracles in the New Testament were more like myths. Later, she also translated Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity in 1854. The ideas from these books influenced her own novels.

Mary Ann started to question her own religious faith. Her father was upset by this, but she continued to live with him and care for him until he died in 1849. After his death, she traveled to Switzerland. She stayed there alone for a while, reading and enjoying the beautiful countryside.

Life in London

In 1850, Mary Ann moved to London to become a writer. She started calling herself Marian Evans. She became an assistant editor for a magazine called The Westminster Review in 1851. Even though someone else was officially the editor, Marian did most of the work. She wrote many essays and reviews for the magazine.

In her writings, she shared her thoughts on society. She cared about the working class and often criticized organized religion. She used her own experiences and knowledge to write about the ideas of her time. Her writing was seen as honest and wise.

Her Relationship with George Lewes

In 1851, Marian met George Henry Lewes. He was a writer and thinker. By 1854, they decided to live together. Lewes was already married, but he and his wife had an unusual arrangement. Marian and Lewes considered themselves married, even though they couldn't legally marry at the time.

This relationship was not accepted by everyone in society back then. However, Lewes gave Marian the support and encouragement she needed to write her novels. She even started signing her name as Mary Ann Evans Lewes. It took a long time for them to be fully accepted by polite society. But in 1877, they were even introduced to Princess Louise, the daughter of Queen Victoria. Queen Victoria herself loved George Eliot's novels.

Becoming a Novelist

While still writing for The Westminster Review, Marian decided to write novels. She wrote an essay called "Silly Novels by Lady Novelists" (1856). In it, she criticized the silly plots of many novels written by women at the time. She believed novels should be realistic.

She chose the pen name George Eliot. She explained that George was Lewes's first name. She wanted her books to be judged on their own merit, not based on her being a woman. At that time, people sometimes didn't take women writers as seriously. Also, using a pen name helped keep her private life, especially her relationship with Lewes, out of the public eye.

In 1857, her first story, "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton," was published. It was part of a collection called Scenes of Clerical Life. People liked it and thought it was written by a country priest.

Her first full novel, Adam Bede (1859), was a huge success right away. People were very curious about who George Eliot was. Eventually, Marian Evans Lewes revealed that she was the author.

George Eliot was influenced by writer Thomas Carlyle. He helped her think about German ideas and shaped her thoughts on work, duty, and understanding others. These ideas appeared in her novels.

Eliot continued to write popular novels for the next fifteen years. These included The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), and her most famous, Middlemarch (1871–1872).

She supported the Union during the American Civil War. She also supported the idea of Irish home rule. She was influenced by the ideas of John Stuart Mill, a philosopher who supported women's rights. She agreed with his efforts to give women the right to vote and better education.

Her last novel was Daniel Deronda, published in 1876. After this, she and Lewes moved to Witley, Surrey. Lewes's health was failing, and he died in 1878.

Marriage and Death

After Lewes died, Eliot spent two years editing his final work. She found comfort with John Walter Cross, a man 20 years younger than her. They married on May 16, 1880. She changed her name again, this time to Mary Ann Cross. Her brother Isaac, who had not spoken to her since she started living with Lewes, sent his congratulations.

They moved to a new house in Chelsea, London. But Eliot became ill with a throat infection. She also had kidney disease for several years. She died on December 22, 1880, at the age of 61.

Because of her views on faith and her relationship with Lewes, George Eliot was not buried in Westminster Abbey. Instead, she was buried in Highgate Cemetery in London. This area was for people who held different religious or political views. She was buried next to George Henry Lewes.

Many places in her hometown of Nuneaton are named after her. These include The George Eliot Academy and George Eliot Hospital. There is also a statue of her in Nuneaton. The Nuneaton Museum & Art Gallery has items related to her life.

Literary Style

George Eliot wrote with a keen understanding of politics and society. In her novels, she often wrote about people who were outsiders or faced challenges in small towns. Felix Holt, the Radical and Middlemarch deal with political changes. Middlemarch is known for its deep look into characters' minds and feelings.

Victorian readers loved her novels because they showed rural life so well. She used her own experiences to create her stories. She believed there was beauty in the everyday details of country life.

Eliot also wrote about other places. Romola is a historical novel set in 15th-century Florence, Italy. She also wrote poetry, but her novels are more famous today.

As a translator, Eliot read many German books about religion and philosophy. Ideas from these books appeared in her novels. She often wrote with a sense of humanism, focusing on human values and experiences. Even though she wasn't religious herself, she respected religious traditions. She saw how they helped keep society orderly and moral.

Her own childhood experiences, especially with religion, influenced characters like Maggie Tulliver in The Mill on the Floss. She also explored what happens when someone feels separated from their community, like Silas Marner.

Later in her career, her book sales started to slow down. After she died, her husband wrote a biography that made her seem like a perfect, saintly woman. This didn't quite match the more complex life people knew she had lived.

In the 20th century, new critics praised her work. Virginia Woolf called Middlemarch "one of the few English novels written for grown-up people." In 2007, Time magazine's poll of authors ranked Middlemarch as the tenth greatest literary work ever. In 2015, writers from outside the UK voted it the best British novel by far. Many of her books have been made into movies and TV shows, which has helped new readers discover her work.

Works

Novels

- Adam Bede, 1859

- The Mill on the Floss, 1860

- Silas Marner, 1861

- Romola, 1863

- Felix Holt, the Radical, 1866

- Middlemarch, 1871–72

- Daniel Deronda, 1876

Short Stories and Novellas

- Scenes of Clerical Life, 1857

- The Sad Fortunes of the Rev. Amos Barton

- Mr Gilfil's Love Story

- Janet's Repentance

- The Lifted Veil, 1859

- Brother Jacob, 1864

- Impressions of Theophrastus Such, 1879

Translations

- The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined by David Strauss, 1846

- The Essence of Christianity by Ludwig Feuerbach, 1854

- The Ethics of Benedict de Spinoza by Benedict de Spinoza, 1856

Poetry

- In a London Drawingroom, 1865

- A Minor Prophet, 1865

- Two Lovers, 1866

- The Choir Invisible, 1867

- The Spanish Gypsy, 1868

- Agatha, 1868

- Brother and Sister, 1869

- How Lisa Loved the King, 1869

- Armgart, 1870

- Stradivarius, 1873

- Arion, 1873

- The Legend of Jubal, 1874

- I Grant You Ample Leave, 1874

- Evenings Come and Go, Love, 1878

- Self and Life, 1879

- A College Breakfast Party, 1879

- The Death of Moses, 1879

Non-fiction

- "Three Months in Weimar", 1855

- "Silly Novels by Lady Novelists", 1856

- "The Natural History of German Life", 1856

- Review of John Ruskin's Modern Painters in Westminster Review, April 1856

- "The Influence of Rationalism", 1865

Images for kids

-

Nuneaton Museum and Art Gallery, which has a collection about George Eliot.

See also

In Spanish: George Eliot para niños

In Spanish: George Eliot para niños