Nicholas of Cusa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

His Eminence

Nicholas of Cusa

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

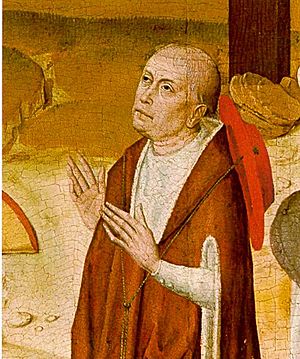

Nicholas of Cusa, by Master of the Life of the Virgin

|

|||||||||||||

| Born | 1401 |

||||||||||||

| Died | 11 August 1464 |

||||||||||||

| Other names | Doctor Christianus, "Nicolaus Chrypffs", "Nicholas of Kues", "Nicolaus Cusanus" | ||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Heidelberg University University of Padua |

||||||||||||

| Era | Medieval philosophy Renaissance philosophy |

||||||||||||

| Region | Western philosophy | ||||||||||||

| School | Renaissance humanism Christian humanism |

||||||||||||

|

Main interests

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Notable ideas

|

Learned Ignorance, Coincidence of Opposites | ||||||||||||

|

Influences

|

|||||||||||||

|

Influenced

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Nicholas of Cusa (born 1401 – died 11 August 1464) was a very important German thinker. He was a cardinal in the Catholic Church, a philosopher, theologian, jurist, mathematician, and astronomer. He was one of the first people in Germany to support Renaissance humanism, a movement that focused on human values and achievements.

Nicholas made big contributions to European history through his spiritual ideas and political work. For example, he wrote about "learned ignorance," which was a deep spiritual concept. He also played a part in power struggles between Rome (the Pope's government) and the German states of the Holy Roman Empire.

Because of his hard work, Pope Nicholas V made him a cardinal in 1448. Two years later, he became the Prince–Bishop of Brixen. In 1459, he was made a special assistant to the Pope in the Papal States. Nicholas is still an influential person today. In 2001, people all over the world celebrated 600 years since his birth.

Contents

Nicholas's Early Life

Nicholas was born in a town called Kues in southwestern Germany. His father, Johan Krebs, was a successful boat owner. Nicholas was the second of four children.

In 1416, he started studying at Heidelberg University. He then earned a doctorate in church law from the University of Padua in Italy in 1423. In Padua, he met important people like future cardinals and a mathematician named Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli. After that, he went to the University of Cologne in 1425, where he taught and practiced church law.

Diplomat and Reformer

Nicholas returned to his hometown and became a secretary for the Prince–Archbishop of Trier. He was also made a canon and dean at a church in Koblenz. In 1427, he went to Rome as a church representative. The next year, he traveled to Paris to study old writings.

He was very good at studying old manuscripts and finding out if they were real. In 1433, he discovered that a famous document called the Donation of Constantine was a fake. This was later confirmed by another scholar. He also found that other church documents were forgeries. Nicholas also worked with an astronomer to try and fix the Julian calendar, but this change didn't happen until the Gregorian calendar was introduced much later in 1582.

Church Councils and Papal Service

In 1432, Nicholas attended the Council of Basel. He represented a claimant to the Archbishop of Trier position. Nicholas argued that the church leaders should have a say in choosing their leaders, even the Pope. Although his efforts didn't help his candidate, they showed his skill as a diplomat. At the council, he wrote his first major work, De concordantia catholica (The Catholic Concordance). This book talked about how the church and empire should work together.

Nicholas later supported moving the council to Italy to meet with Greek church leaders. He helped settle conflicts with the Hussites, a religious group. In 1437, he traveled to Constantinople to bring the Byzantine emperor to the Council of Florence in 1439. This council tried to unite the Eastern Orthodox Church with the Western Catholic Church, but the union didn't last long. Nicholas later said that his idea for his famous book, On Learned Ignorance, came to him during his return trip from Constantinople.

Cardinal and Bishop

After a successful career as a papal envoy, Pope Nicholas V made him a cardinal in 1448 or 1449. In 1450, he was named Bishop of Brixen and sent to Germany to spread ideas of church reform. He traveled almost 3,000 miles, preaching and teaching. He was known as the "Hercules of the Eugenian cause" because of his strong support for the Pope.

However, his efforts to reform the church and get back church money were met with resistance. Duke Sigismund of Austria even imprisoned Nicholas in 1460. Because of this, Pope Pius II excommunicated Sigismund, meaning he was cut off from the church. Nicholas returned to Rome and could never go back to his bishopric.

Nicholas died in Todi, Italy, on 11 August 1464. His body was buried in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome. His monument is still there. However, his heart was buried in the chapel altar at the Cusanusstift in Kues. This was a charitable institution he founded to care for the elderly. He left all his money to this institution, which still exists today. It also holds many of his old writings.

Nicholas's Philosophy

Nicholas's most famous philosophical work is De Docta Ignorantia (On Learned Ignorance). In this book, he explained that the human mind is limited and cannot fully understand God, who is infinite. However, he believed that by realizing our limits in knowing God, we can achieve "learned ignorance." This means we become wise by understanding what we cannot know.

Nicholas also wrote deeply mystical texts about Christianity. He talked about how everything in creation is connected to God. Some people thought his ideas were close to pantheism (the belief that God is everything), but his writings were never considered heretical (against church teachings). In another work, De coniecturis, he wrote about using guesses or ideas to get closer to the truth.

Science and Mathematics

Nicholas was also interested in science and mathematics. Many of his mathematical ideas are found in his philosophical essays. He wrote about how mathematical shapes can help the mind understand how things change. This prepares the mind to see the "coincidence of opposites" in God, meaning that in God, all opposing ideas come together. Like another scholar named Nicole Oresme, Nicholas also thought about the possibility of other worlds existing.

Nicholas's Political Ideas

In 1433, Nicholas suggested a way to reform the Holy Roman Empire and elect its emperors. His method was very similar to what is now called the Borda count, which is used in many elections and competitions today. He came up with this idea over 300 years before it was officially named.

Nicholas believed that government should be based on the consent of the governed. This means that leaders get their power from the people they rule. He wrote:

- Since by nature all men are free, any authority that stops people from doing wrong and guides them to do good comes only from agreement and the consent of the people. This is true whether the authority is in written laws or in the ruler. If all people are naturally equal in strength and freedom, then the true power of one person over others can only be set up by the choice and agreement of those others, just like a law is made by agreement.

Ideas on Other Religions

After the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, Nicholas wrote De pace fidei (On the Peace of Faith). This book imagined a meeting in Heaven with representatives from all nations and religions, including Islam and the Hussite movement. The meeting agrees that there can be "one faith in a variety of rites." This means that there is one main faith, but it can be shown in different ways, just like the different ways of worship in the Catholic Church. This book showed respect for other religions.

He also wrote Cribratio Alchorani (Sifting the Koran), which was a detailed review of the Koran in Latin. While this book still argued that Christianity was superior, it also gave credit to Judaism and Islam for having some truth.

Nicholas's Influence

Nicholas's works were read widely and published in the 1500s. However, his ideas were largely forgotten until the 1800s. Some later thinkers, like Giordano Bruno and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, were thought to have been influenced by him. In the early 1900s, scholars began to study Nicholas again. Some called him the "first modern thinker," leading to debates about whether he was more of a medieval or Renaissance figure.

Today, there are groups and centers dedicated to Nicholas in many countries, including Argentina, Japan, Germany, Italy, and the United States.

Nicholas's Works

Nicholas wrote many books and essays, including:

- De concordantia catholica (The Catholic Concordance) (1434) – about the church and empire working together.

- De Docta ignorantia (On Learned Ignorance) (1440) – his most famous philosophical work.

- De coniecturis (On Conjectures) (1441-2) – about using ideas to understand truth.

- Apologia doctae ignorantiae (The Defense of Learned Ignorance) (1449) – his response to people who accused him of heresy.

- Idiota de mente (The Layman on Mind) (1450) – a series of dialogues.

- De visione Dei (On the Vision of God) (1453) – written for monks.

- De pace fidei (On the Peace of Faith) (1453) – about different religions.

- Cribratio Alkorani (Sifting the Koran) – a review of the Koran.

- De ludo globi (On the Game of the Globe) (1463) – about a game with a globe.

- De apice theoriae (On the Summit of Contemplation) (1464) – his last work.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Nicolás de Cusa para niños

In Spanish: Nicolás de Cusa para niños

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics

- Università degli Studi Niccolò Cusano

- Absolute (philosophy)

- I know that I know nothing

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |