Nicole Oresme facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nicole Oresme

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait of Nicole Oresme: Miniature from Oresme's Traité de l'espère, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, France, fonds français 565, fol. 1r.

|

|

| Born | c. 1325 Fleury-sur-Orne, Normandy, France

|

| Died | 11 July 1382 |

| Alma mater | College of Navarre (University of Paris) |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Nominalism |

| Institutions | College of Navarre (University of Paris) |

|

Main interests

|

Natural philosophy, astronomy, theology, mathematics |

|

Notable ideas

|

Rectangular co-ordinates, first proof of the divergence of the harmonic series, mean speed theorem |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Nicole Oresme (French: [nikɔl ɔʁɛm]; born around 1320–1325 – died July 11, 1382) was an important French thinker from the later Middle Ages. He was also known as Nicolas Oresme or Nicholas Oresme. He wrote many influential books on topics like economics, mathematics, physics, astronomy, and philosophy.

Oresme was also a Bishop of Lisieux, a translator, and an advisor to King Charles V of France. He is considered one of the most original thinkers of the 14th century in Europe.

Contents

Life of Nicole Oresme

Nicole Oresme was born between 1320 and 1325 in a small village called Allemagnes, which is now Fleury-sur-Orne in Normandy, France. We don't know much about his family. However, he attended the College of Navarre in Paris. This college was for students who were too poor to pay for their studies at the University of Paris. This suggests that Oresme likely came from a farming family.

Oresme studied the "arts" in Paris. He studied alongside other famous thinkers like Jean Buridan and Albert of Saxony. By 1342, he had earned his Master of Arts degree. In 1348, he began studying theology in Paris.

He received his doctorate in 1356. In the same year, he became the grand master of the College of Navarre. Later, in 1364, he was made the dean of the Cathedral of Rouen.

Around 1369, King Charles V of France asked Oresme to translate the works of Aristotle. The King gave him a special payment in 1371. With the King's support, Oresme became the bishop of Lisieux in 1377. He died in Lisieux in 1382.

Nicole Oresme's Scientific Discoveries

Thinking About the Universe

In his book Livre du ciel et du monde (meaning "Book of the Sky and the World"), Oresme discussed whether the Earth spins on its axis every day. He said that if the Earth moved instead of the celestial spheres (the idea that stars and planets were on rotating crystal spheres), everything we see in the sky would look exactly the same.

He also thought about the argument that if the Earth moved, the air would be left behind, causing a huge wind. Oresme believed that the Earth, water, and air would all move together. He also noted that it would be simpler for the small Earth to spin than for the huge sphere of stars to rotate.

Oresme also looked at parts of the Bible that talk about the Sun moving. He concluded that these passages were just "common ways of speaking" and shouldn't be taken literally. Despite all these ideas, he still believed that "the heavens do move and not the Earth."

Challenging Astrology

Oresme also studied astrology, which is the belief that the positions of stars and planets affect human events. He developed ideas about "incommensurate fractions." These are fractions that cannot be easily compared to each other. He used this to argue that it's very likely that the length of a day and a year are incommensurate. This also applies to the movements of the moon and planets.

Because of this, Oresme said that planetary alignments would never happen in exactly the same way twice. He used this to challenge astrologers. He argued that they couldn't know the exact movements of planets and therefore couldn't accurately predict the future.

Oresme looked at astrology in six parts in his book Livre de divinacions.

- The first part, which is basically astronomy, he considered a good science. However, he believed it couldn't be known with perfect accuracy.

- The second part was about how heavenly bodies influence events on Earth. Oresme didn't deny this influence. But he said it could be either a symbolic sign or a direct cause.

- The third part was about predicting events like plagues, famines, and weather. Oresme criticized these predictions as often wrong. He noted that sailors and farmers were better at predicting weather than astrologers. He also pointed out that the zodiac had shifted over time due to precession of the equinoxes.

The last three parts of astrology, according to Oresme, were about fortune.

- "Interrogations" meant asking the stars when to do things like business deals.

- "Elections" meant choosing the best time for events like getting married or fighting a war.

- "Nativities" involved birth charts to predict a person's life.

Oresme called interrogations and elections "totally false." For nativities, he was more careful. He believed that human beings have free will, so no path is completely decided by the stars. However, he accepted that heavenly bodies could influence a person's mood or behavior. Overall, Oresme was very skeptical of astrology, especially its ability to predict specific events.

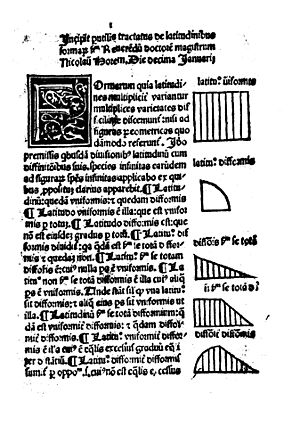

Mathematics and Graphs

Oresme made very important contributions to mathematics in his book Tractatus de configurationibus qualitatum et motuum. He had an idea to show qualities, like heat, using pictures. He imagined drawing a line for the "length" of something, like a heated rod. Then, at each point on that line, he would draw another line straight up to show the "intensity" or degree of heat at that point.

This idea was very similar to what we now call rectangular coordinates or graphs. He suggested that the shape of this drawing could represent the quality itself. For example, a constant quality would be a straight line. A quality that changed steadily would be a slanted straight line.

Oresme applied this idea to movement. He used the horizontal line for time and the vertical line for speed. The area of the shape created by these lines would then represent the distance traveled. This was a very early way of showing how speed changes over time. He even showed that his method could describe how an object moves when its speed changes steadily. This was a key idea that Galileo Galilei later made famous, centuries after Oresme. Some historians even say Oresme's diagrams were like early "bar charts."

Oresme also proved that the harmonic series (1 + 1/2 + 1/3 + 1/4 + ...) goes on forever and doesn't add up to a fixed number. This is called a divergent series. His proof was very clever and didn't need advanced math. He showed that you can always find groups of terms that add up to at least 1/2, no matter how far you go in the series. This means the sum keeps growing without limit.

He was the first mathematician to prove this. After his proof was forgotten, it wasn't proven again until the 17th century. Oresme also worked on ideas like fractional powers and probability, which were far ahead of his time.

Political Ideas

Oresme was the first person to translate Aristotle's important books on ethics and politics into Middle French. He also added his own comments, sharing his political views. Like other thinkers before him, Oresme believed that monarchy (having a king or queen) was the best form of government.

He thought a good ruler should always work for the "common good" of everyone, not just for their own benefit. He also believed that people should have a say in government, but only wise and reasonable men. However, Oresme was clear that people should never rebel, as this would harm the common good.

Unlike some thinkers of his time, Oresme believed that the law was more important than the king's wishes. Laws should only be changed if absolutely necessary. He favored a king with moderate power, not an absolute ruler who could do anything they wanted.

Oresme also criticized the Catholic Church for being corrupt and too powerful. However, he never questioned that the Church was needed for people's spiritual well-being. His translations and ideas likely influenced King Charles V's decisions about how the kingdom should be run.

Economic Views

Oresme wrote one of the earliest books focused on economic matters, called Treatise on the origin, nature, law, and alterations of money. He believed that people have a natural right to own property. This property belongs to the individual and the community.

He also discussed how a ruler should be held responsible for putting the common good before their own interests. While a ruler might have claims on money in an emergency, Oresme said that any ruler who abuses this power is a "Tyrant dominating slaves." Oresme was one of the first medieval thinkers to challenge the idea that a monarch had a right to all money. He strongly supported the right of people to own private property.

Later Recognition

Oresme's ideas on economics continued to be respected for many centuries after his death.

Selected Works in English

- Nicole Oresme's De visione stellarum (On seeing the stars): a critical edition of Oresme's treatise on optics and atmospheric refraction, translated by Dan Burton, (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2007, ISBN: 9789004153707)

- Nicole Oresme and the marvels of nature: a study of his De causis mirabilium, translated by Bert Hansen, (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1985, ISBN: 9780888440686)

- Questiones super quatuor libros meteororum, in SC McCluskey, ed, Nicole Oresme on Light, Color and the Rainbow: An Edition and Translation, with introduction and critical notes, of Part of Book Three of his Questiones super quatuor libros meteororum (PhD dissertation, University of Wisconsin, 1974, Google Books)

- Nicole Oresme and the kinematics of circular motion: Tractatus de commensurabilitate vel incommensurabilitate motuum celi, translated by Edward Grant, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1971)

- Nicole Oresme and the medieval geometry of qualities and motions: a treatise on the uniformity and difformity of intensities known as Tractatus de configurationibus qualitatum et motuum, translated by Marshall Clagett, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1971, )

- Le Livre du ciel et du monde. A. D. Menut and A. J. Denomy, ed. and trans. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968, ISBN: 9780783797878)

- De proportionibus proportionum and Ad pauca respicientes. Edward Grant, ed. and trans. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1966, ISBN: 9780299040000)

- The De moneta of N. Oresme, and English Mint documents, translated by C. Johnson, (London, 1956)

See also

In Spanish: Nicolás Oresme para niños

In Spanish: Nicolás Oresme para niños

- List of multiple discoveries

- Science in the Middle Ages

- Oresme (crater)

- List of Roman Catholic scientist-clerics