Medieval philosophy facts for kids

Medieval philosophy is the way people thought about big questions during the Middle Ages. This time period stretched from around the 5th century (when the Western Roman Empire fell) to the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy started in places like Baghdad and France in the late 700s. It was about two main things: finding and understanding old ideas from Greece and Rome, and trying to connect religious beliefs (theology) with everyday learning.

The history of medieval philosophy is usually split into two parts. The first part, in Western Europe, lasted until the 12th century. During this time, old writings by thinkers like Aristotle and Plato were found again, translated into Latin, and studied. The second part, from the 12th to 14th centuries, was a "golden age." More ancient ideas were recovered, and thinkers learned from Arabic scholars. Important new ideas came out in areas like the philosophy of religion, logic, and metaphysics.

Later thinkers during the Renaissance didn't always like medieval philosophy. They thought it was a "middle period" between the great times of Greece and Rome and their own "rebirth" of classical culture. But today, historians see the medieval era as a time of important philosophical growth. It was greatly shaped by Christian theology. One famous thinker, Thomas of Aquinas, didn't even call himself a philosopher. He believed philosophy often didn't reach the "true wisdom" found in faith.

During this period, people discussed many big questions. These included how faith and reason work together, if God exists and what God is like, the purpose of theology and metaphysics, and how we gain knowledge. They also wondered about universals (what makes things part of a group) and individuation (what makes each thing unique).

Contents

What Made Medieval Philosophy Special?

Medieval philosophy focused a lot on religious ideas. Most medieval thinkers, except perhaps Avicenna and Averroes, didn't see themselves as philosophers. For them, philosophers were ancient non-Christian writers like Plato and Aristotle. However, these medieval thinkers used the methods and logic of ancient philosophers. They used them to explore difficult religious questions and beliefs.

Thomas Aquinas said that philosophy was like a helper to theology (ancilla theologiae). Even with this view, medieval thinkers still created new and clever philosophies. They did this while working on their religious projects. For example, thinkers like Augustine of Hippo and Thomas of Aquinas made huge advances. Augustine explored the idea of time, and Aquinas made breakthroughs in metaphysics (the study of reality).

Here are the main ideas behind all medieval philosophers' work:

- Using logic, debate, and analysis to find the truth. This was called ratio.

- Respecting the ideas of ancient philosophers, especially Aristotle. They looked to them as authorities (auctoritas).

- Making sure philosophical ideas fit with religious teachings and revelations (concordia).

One of the most debated topics was faith versus reason. Avicenna and Averroes favored reason more. Augustine said his philosophical studies would never go beyond God's authority. Anselm tried to defend faith while allowing for both faith and reason. Augustine's way to solve the faith/reason problem was to first believe, then try to understand (fides quaerens intellectum).

A Look at Medieval Philosophy Through Time

Early Christian Philosophy in the Middle Ages

The early medieval period usually starts with Augustine (354–430 AD). He was a classical thinker, but his ideas shaped the Middle Ages. This period ends with a new burst of learning in the late 11th century.

After the Roman empire fell, Western Europe entered a time sometimes called the Dark Ages. Monasteries became important places for learning. This was partly because St Benedict's rule in 525 AD asked monks to read the Bible daily. Later, monks were trained to become administrators and church leaders.

Early Christian thought, especially from the Church Fathers, was often based on feelings and spiritual experiences. It relied less on pure reason and logical arguments. It also focused more on the ideas of Plato, which sometimes seemed mystical. It focused less on the organized thinking of Aristotle. Much of Aristotle's work was not known in the West at this time. Scholars used Latin translations by Boethius of Aristotle's Categories and On Interpretation. They also used his translation of Porphyry's Isagoge, which was a commentary on Aristotle's Categories.

Two Roman philosophers greatly influenced medieval philosophy: Augustine and Boethius. Augustine is seen as the greatest of the Church Fathers. He was mainly a religious writer, but much of his work was philosophical. He wrote about truth, God, the human soul, the meaning of history, the state, sin, and salvation. For over a thousand years, almost every Latin religious or philosophical book quoted him. Some of his ideas even influenced later thinkers like Descartes.

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius (around 480–524 AD) was a Christian philosopher from a powerful Roman family. He became a high official in 510 AD. His influence on the early medieval period was so strong that it's sometimes called the Boethian period. He planned to translate all of Aristotle's and Plato's works from Greek into Latin. He translated many of Aristotle's logic books. He also wrote commentaries on these works and on Porphyry's Isagoge. This introduced the problem of universals to the medieval world.

The first major return of learning in the West happened when Charlemagne became emperor. With advice from scholars like Alcuin of York, Charlemagne brought scholars from England and Ireland. In 787 AD, he ordered schools to be set up in every abbey in his empire. These schools, from which the name Scholasticism comes, became centers of medieval learning.

Johannes Scotus Eriugena (around 815 – 877 AD) was an Irish theologian and Neoplatonic philosopher. He took over from Alcuin of York as head of the Palace School. He is known for translating and writing about the work of Pseudo-Dionysius. This writer was first thought to be from the time of the apostles. Around this time, some religious arguments came up. One was whether God had decided beforehand who would be saved and who would be condemned. Eriugena was asked to help settle this debate. Also, Paschasius Radbertus asked an important question about the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Is the bread the same as Christ's historical body? How can it be in many places at many times? Radbertus argued that Christ's real body is present, hidden by the look of bread and wine. He said it is present everywhere and always, because of God's amazing power.

This time also saw a rise in scholarship. At Fleury, Theodulphus, the bishop of Orléans, started a school for young noblemen. By the mid-9th century, its library was one of the best in the West. Scholars like Lupus of Ferrières (died 862) traveled there to read its books. Later, under St. Abbo of Fleury (abbot 988–1004), Fleury had another great period.

Remigius of Auxerre, in the early 10th century, wrote notes or explanations on classical texts. These included works by Donatus, Priscian, Boethius, and Martianus Capella. After the Carolingian period, there was a short "dark age." This was followed by a lasting return of learning in the 11th century. This new learning owed a lot to finding Greek ideas again through Arabic translations. It also benefited from Muslim contributions like Avicenna's book On the soul.

The High Middle Ages

The period from the mid-11th century to the mid-14th century is called the 'High medieval' or 'scholastic' period. It is usually said to begin with Saint Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109). He was an Italian philosopher, theologian, and church leader. He is famous for creating the ontological argument for the existence of God.

The 13th and early 14th centuries are seen as the peak of scholasticism. The early 13th century saw the full return of Greek philosophy. Translation schools grew in Italy, Sicily, and then across Europe. Scholars like Adelard of Bath traveled to Sicily and the Arab world. They translated books on astronomy and mathematics, including the first full translation of Euclid's Elements. Powerful Norman kings brought knowledgeable people to their courts to show their importance. William of Moerbeke's translations of Greek philosophical texts in the mid-13th century helped people understand Greek philosophy better. This was especially true for Aristotle. The Arabic versions they had used before sometimes changed or hid the links between Plato's and Aristotle's ideas. Moerbeke's work became the basis for the important commentaries that followed.

Universities grew in Europe's big cities during this time. Different religious groups within the Church started to compete for power and control over these learning centers. The two main groups founded then were the Franciscans and the Dominicans. The Franciscans were started by Francis of Assisi in 1209. Their leader in the mid-century was Bonaventure. He was a traditional thinker who defended the ideas of Augustine and Plato. He only used a little of Aristotle's ideas, mixing them with more Neoplatonic elements. Like Anselm, Bonaventure believed that reason could find truth only when philosophy was guided by religious faith. Other important Franciscan writers were Duns Scotus, Peter Auriol, and William of Ockham.

In contrast, the Dominican order, founded by St Dominic in 1215, focused more on using reason. They used a lot of the new Aristotelian writings that came from the East and Moorish Spain. The great Dominican thinkers of this period were Albertus Magnus and, especially, Thomas Aquinas. Aquinas skillfully combined Greek reason with Christian beliefs. His ideas eventually became the main Catholic philosophy. Aquinas put more emphasis on reason and arguments. He was one of the first to use the new translations of Aristotle's writings on metaphysics and knowledge. This was a big change from the Neoplatonic and Augustinian ideas that had ruled early Scholasticism. Aquinas showed how to use much of Aristotle's philosophy without falling into the "mistakes" of the commentator Averroes.

In the early 20th century, historian Martin Grabmann was the first scholar to map out how scholastic thought developed. He saw Thomas Aquinas's work as a response and growth of ideas, not just one complete system. Grabmann's work was key to how we understand scholasticism today and Aquinas's central role in it.

Key Topics in Medieval Philosophy

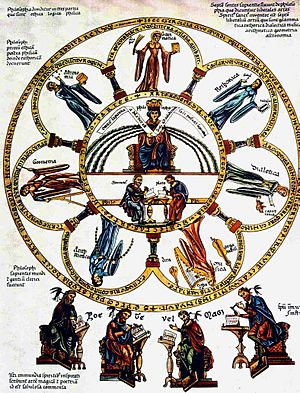

All the main areas of philosophy we study today were once part of Medieval philosophy. Medieval philosophy also covered most of the topics first explored by ancient non-Christian philosophers, especially Aristotle. However, the field now called Philosophy of religion was a unique development of the Middle Ages. Many of the questions that define this subject first appeared in the Middle Ages, and we still recognize them today.

Religious Ideas (Theology)

Medieval philosophy is very much about religious ideas. Topics discussed during this time included:

- God's qualities: How can God have qualities like unlimited power, knowing everything, perfect goodness, and existing outside time, all at once? Do these qualities make sense together?

- The problem of evil: Ancient philosophers wondered about evil. But the question of how an all-powerful, all-knowing, loving God could create a world where evil exists first came up in the medieval period.

- Free will: Another similar problem was explaining how God's "foreknowledge" (knowing what will happen in the future) fits with our belief that we have free will.

- The soul's immortality: Questions about whether the mind can live forever, if the soul and mind are one, and why we believe the soul is immortal.

- Non-material beings: The question of whether there can be beings that are not made of matter, like angels.

Metaphysics (Study of Reality)

After Aristotle's Metaphysics was "rediscovered" in the mid-12th century, many scholars wrote about it. Aquinas and Scotus were two of them. The problem of universals was one of the main issues discussed then. Other topics included:

- Hylomorphism: This built on Aristotle's idea that individual things are a mix of material and form. For example, a statue is made of granite, but it also has the shape (form) carved into it.

- Existence: What it means for something to "be" or "exist."

- Causality: Discussions about cause and effect mostly involved explaining Aristotle's works. These included Physics, On the Heavens, and On Generation and Corruption. The medieval approach to this was unique. They saw studying the universe as a way to understand God. Duns Scotus's proof for God's existence is based on the idea of causality.

- Individuation: This problem asks how we can tell apart or count the individual members of any group. It came up when people needed to explain how individual angels of the same kind could be different. Angels are not material, so their differences can't be explained by what they are made of. The main thinkers on this were Aquinas and Scotus.

Natural Philosophy (Early Science)

In natural philosophy (what we now call science) and the philosophy of science, medieval philosophers were mainly influenced by Aristotle. However, from the 14th century onwards, they started using more mathematical reasoning in natural philosophy. This helped prepare the way for the rise of modern science. The mathematical thinking of William Heytesbury and William of Ockham shows this trend. Other thinkers in natural philosophy included Albert of Saxony, John Buridan, and Nicholas of Autrecourt. Some historians believe there was a continuous development from medieval thought to the Renaissance and early modern science.

Logic (How We Reason)

The famous historian of logic, I. M. Bochenski, thought the Middle Ages was one of the three great periods in the history of logic. From the time of Abelard until the mid-14th century, scholars greatly improved and developed Aristotelian logic. Earlier, writers like Peter Abelard wrote explanations of Aristotle's Categories, On interpretation, and Porphyry's Isagoge. Later, new areas of logic appeared, and new ideas about logic and meaning were developed. Important topics in medieval logic included insolubilia (paradoxes), obligations (logical games), properties of terms (how words refer), syllogism (types of arguments), and sophismata (tricky arguments). Other great contributors to medieval logic were Albert of Saxony, John Buridan, John Wyclif, Paul of Venice, Peter of Spain, Richard Kilvington, Walter Burley, William Heytesbury, and William of Ockham.

Philosophy of Mind (How Our Minds Work)

Medieval philosophy of mind was based on Aristotle's De Anima (On the Soul). This book was also found in the Latin West in the 12th century. It was seen as a part of natural philosophy. Some of the topics discussed in this area included:

- Divine illumination: This idea said that humans need special help from God to think normally. This idea is most linked to Augustine and his followers. It appeared again in a different way in the early modern era.

- Mental representation: The idea that our mental states have "intentionality." This means that even though they are in our minds, they can represent things outside our minds. This idea is key to modern philosophy of mind. It started in medieval philosophy. (The word 'intentionality' was brought back by Franz Brentano, who wanted to use it like medieval thinkers did). Ockham is known for his idea that language mainly means mental states by agreement. Real things are secondary. But mental states themselves directly and necessarily mean real things.

Writers in this area included Saint Augustine, Duns Scotus, Nicholas of Autrecourt, Thomas Aquinas, and William of Ockham.

Ethics (Right and Wrong)

Abu Nasr al-Farabi was a well-known figure in medieval Islamic philosophy and ethics. He wrote in a simple, narrative style, telling stories with subtle ideas about ethics.

Al-Farabi's Contributions: In his stories, al-Farabi discussed ethical and philosophical ideas. He linked them to politics, leadership, morals, faith, and civics. One important work is The Attainment of Happiness. In it, al-Farabi argued that ideas about politics and religion must be built on understanding the universe. He believed you must first form ideas about universal matters to have fair opinions on political philosophy and religion. These two subjects were very important in his work. He often wrote about how politics and religion fit together. For example, he claimed that both political and religious leaders are connected to a basic understanding of the universe.

Other writers in this area included Anselm, Augustine, Peter Abelard, Scotus, Peter of Spain, Aquinas, and Ockham. Writers on political theory included Dante, John Wyclif, and William of Ockham.

|

See Also

In Spanish: Filosofía medieval para niños

In Spanish: Filosofía medieval para niños

- Christian philosophy

- Early Muslim philosophy

- Jewish philosophy

- Nominalism

- Renaissance of the 12th century

- Scholastic philosophy

- Supposition theory

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |