Adelard of Bath facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Adelard of Bath

|

|

|---|---|

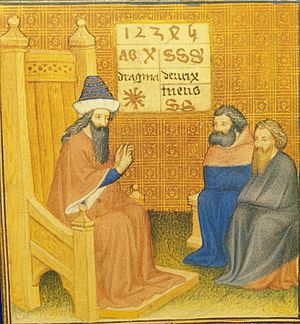

Adelard of Bath, teaching

illuminated by Virgil Master (c. 1400) in the Regulae abaci manuscript SCA 1 |

|

| Born | c. 1080? |

| Died | c. 1142-1152? Bath, Somerset

|

|

Notable work

|

Euclid's Elements (Translation from Arabic), Natural Questions, Treatise on the Astrolabe |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Scholasticism |

|

Main interests

|

Science, theology, algebra, geometry, alchemy, astrology, astronomy |

|

Influences

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Adelard of Bath (born around 1080, died around 1142-1152) was an English thinker and scientist from the 12th century. He is famous for his own ideas and for translating many important Greek science books into Latin. These books covered subjects like astronomy (the study of stars and planets), mathematics, and philosophy (the study of knowledge and existence).

Adelard translated these works from Arabic versions, which helped bring new scientific knowledge to Europe. He made the oldest known Latin translation of Euclid's Elements, a very important book about geometry. He was also one of the first people to introduce the Arabic numeral system (like the numbers we use today: 0, 1, 2, 3...) to Europe.

Adelard's work brought together ideas from different places: the schools in France, the Greek culture of Southern Italy, and the advanced Arabic science from the East.

Contents

About Adelard of Bath

Adelard's life story isn't fully known, so some parts are open to different ideas. We know much of what he did from his own writings.

Adelard said he came from the Roman English city of Bath. How he lived his daily life isn't completely clear. Even though he traveled a lot, it's thought he returned to Bath by the end of his life, where he passed away.

His parents are not known for sure. Some experts think a man named Fastred, who rented land from the Bishop of Wells, might have been his father. The name Adelard is from Anglo-Saxon times. This might mean he was not from a high-ranking family in 11th-century England.

It's believed he left England around the late 1000s to go to Tours, a city in France. This was probably suggested by Bishop John de Villula. While studying in Tours, an unknown "wise man" sparked Adelard's interest in astronomy. Later, Adelard taught for a while in Laon, another French city, before leaving by 1109 to travel.

His Travels and Discoveries

After leaving Laon, Adelard wrote that he traveled to Southern Italy and Sicily by 1116. He also said he traveled widely through areas involved in the Crusades. These included Greece, West Asia, Sicily, possibly Spain, Tarsus, Antioch, and maybe Palestine. The time he spent in these places likely explains his deep interest in mathematics. It also gave him access to Arabic scholars and their knowledge.

Some experts wonder if he truly traveled as much as he claimed. They think he might have used stories of "travel" and talking with "Arabs" to make his own new ideas seem more acceptable.

By 1126, Adelard came back to Western Europe. He wanted to share the knowledge he had learned about Arab astronomy and geometry with the Latin-speaking world. This was a time of big changes and crusades. Adelard's work helped bring many ancient texts and new questions back to England. These ideas later helped start an "English Renaissance" (a time of new learning and art).

In the 11th century, getting an education was hard. Printing had not been invented yet, and most people couldn't read. Books were very rare in medieval Europe. Usually, only royal families or Catholic monasteries had them. Adelard studied with monks at the Benedictine Monastery in Bath Cathedral.

Adelard's Important Books

Adelard of Bath wrote several original books. Some of these were written as dialogues, like conversations, similar to the style of the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. He also wrote letters to his nephew.

On the Same and the Different

One of his earliest works is De Eodem et Diverso, which means On the Same and the Different. This book encourages people to study philosophy. It's similar to Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius. Adelard likely wrote it near Tours, after some of his travels.

The book is a conversation between two characters. Philocosmia argues for worldly pleasures, while Philosophia defends learning. Philosophia's arguments lead to a summary of the seven liberal arts. These were the main subjects taught in medieval schools: grammar, rhetoric, logic, mathematics, geometry, music, and astronomy. The book highlights the difference between what we can see and touch (Philocosmia's view) and ideas or concepts in our minds (Philosophia's view).

Questions on Natural Science

Adelard's most important original work is probably his Questiones Naturales, or Questions on Natural Science. He wrote this book between 1107 and 1133. In it, he mentions that seven years had passed since he taught in schools at Laon.

He wrote this book as if it were a discussion about Arabic learning. He often talked about his experiences in Antioch. The book has 76 questions, presented as a Platonic dialogue (a conversation). These questions are about meteorology (the study of weather) and natural science. This book was widely used in schools for a long time.

Questiones Naturales is divided into three parts:

- On Plants and Brute Animals

- On Man

- On Earth, Water, Air, and Fire

Two key ideas in this book are:

- He preferred using reason and logic to find answers in science and nature, rather than just relying on old beliefs.

- He used the idea of "Arab teachings" when discussing very new or controversial topics. For example, he explored whether animals might have knowledge and souls.

Adelard believed that using reason to seek knowledge did not go against Christian faith. The idea of the soul is a big part of this book. It discusses a physical soul in humans and a non-physical soul in elements and animals. Questiones Naturales was very popular and was copied often. It was even made into a "pocket-book" size, meaning people carried it around.

Other Works

Adelard also wrote a book about using the abacus (an old counting tool) called Regulae Abaci. This was likely one of his first works, as it doesn't show any Arabic influence. This book suggests Adelard might have been connected to the Exchequer, a medieval office that handled money calculations.

He is also known for translating the astronomical tables of al-Khwarizmi. This was the first widely available Latin translation of Islamic ideas about algebra. In the Middle Ages, Adelard was famous for bringing back and teaching geometry. He earned this reputation by making the first full translation of Euclid's Elements and helping Western scholars understand it.

Adelard's Impact

Adelard's work greatly influenced the study of natural philosophy. He especially impacted later thinkers like Robert Grosseteste and Roger Bacon. His work in natural philosophy helped set the stage for much of the scientific progress made after Aristotle.

His translation of Euclid's Elements taught people how to use proofs and geometrical methods. While his early writings showed a love for the seven liberal arts, his Quaestiones naturales showed a deeper interest in subjects like physics, the natural sciences, and metaphysics (the study of the basic nature of reality).

His influence can be seen in the writings of other important scholars. These include De philosophia mundi by William of Conches, works by Hugh of Saint Victor, and Letters to Alcher on the Soul by Isaac of Stella.

Adelard introduced algebra to the Latin-speaking world. His notes and explanations on Euclid's Elements were very important in the 13th century. He showed original scientific thinking. For example, he questioned the shape of the Earth (he believed it was round). He also wondered how the Earth stays still in space. He even thought about a classic physics question: how far would a rock fall if a hole were drilled through the Earth and a rock dropped through it? (This relates to the idea of the center of gravity).

Campanus of Novara likely used Adelard's translation of Elements. Campanus's version was the first to be printed in Venice in 1482, after the invention of the printing press. It became the main textbook for math schools in Western Europe until the 16th century.

See Also

In Spanish: Adelardo de Bath para niños

In Spanish: Adelardo de Bath para niños

- Latin translations of the 12th century

- Guibert of Nogent

- Petrus Alphonsi

- Peter Abelard

- Thierry of Chartres

- Hugh of St. Victor

- William of Conches

- Isaac of Stella

- Peter the Venerable

- Pope Sylvester II

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |