Celestial spheres facts for kids

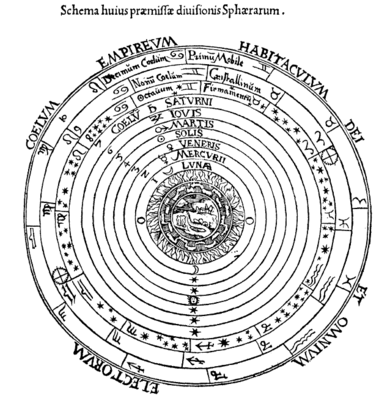

The celestial spheres (or celestial orbs) were a big idea in how people understood the universe long ago. Thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, Ptolemy, and even Copernicus used this idea. They believed that the fixed stars and planets were stuck inside huge, clear, spinning balls, like jewels on an orb. These spheres were thought to be made of a special, see-through material called aether.

People believed the stars didn't move relative to each other. So, they thought all the stars must be on the surface of one giant starry sphere.

Today, we know that planets orbit in mostly empty space. But ancient and medieval thinkers imagined these celestial orbs as thick, layered spheres. They were nested one inside the other, touching the sphere above and below. When astronomers used ideas like epicycles to explain planet movements, they thought each planetary sphere was just thick enough to hold these movements.

By combining this idea with observations, people calculated distances to the Sun and planets. For example, they thought the Sun was about 4 million miles (6 million km) away. They believed the edge of the universe was about 73 million miles (117 million km) away. These distances are very different from what we know today. The universe is now known to be incredibly vast and still growing!

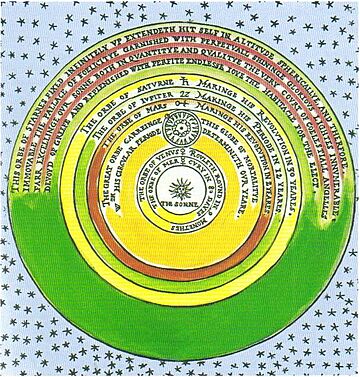

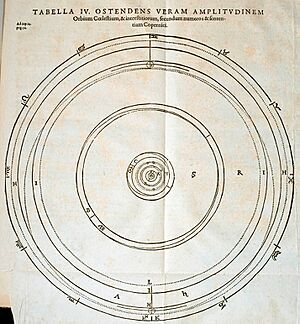

Many educated Europeans knew about this "nesting spheres" model from about 1250 until the 1600s. Even after Nicolaus Copernicus suggested the Sun was at the center (the heliocentric model), new versions of the sphere model appeared. In these, the planets orbited the Sun in this order: Mercury, Venus, Earth (with its Moon), Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

The main belief in celestial spheres faded during the Scientific Revolution. In the early 1600s, Johannes Kepler still talked about spheres. But he thought planets moved in oval paths, not carried by solid spheres. Later in the 1600s, Isaac Newton's ideas about gravity explained how planets move. This replaced the old Greek and medieval theories about spheres.

Contents

How the Idea of Spheres Began

Early Thoughts on Spheres and Circles

In Ancient Greece, the first ideas about celestial spheres came from Anaximander in the 500s BC. He thought the Sun and Moon were like holes in fiery rings. These rings were part of spinning, chariot-like wheels around Earth. The stars were also holes in many such wheels, forming a continuous sphere around Earth. Anaximander believed a giant sphere of fire originally surrounded Earth. This sphere broke into rings, which then formed the stars' sphere. He thought the Sun's ring was highest, then the Moon's, and the stars' sphere was lowest.

After Anaximander, his student Anaximenes (around 585–528 BC) believed stars, Sun, Moon, and planets were made of fire. He thought stars were like nails fixed on a spinning crystal sphere. But the Sun, Moon, and planets just floated on air. Unlike Anaximander, he put the stars farthest from Earth. The idea of stars fixed on a crystal sphere became a key belief until Copernicus and Kepler.

Later, thinkers like Pythagoras and Plato also believed the universe was spherical. Plato's Timaeus (in the 300s BC) said the cosmos was a perfect sphere holding the fixed stars. But he thought planets were spherical bodies in rotating bands or rings, not wheels.

The Rise of Planetary Spheres

Instead of bands, Plato's student Eudoxus created a model using concentric spheres for all planets. He used three spheres for the Moon and Sun, and four for each of the other five planets. This made 26 spheres in total! Callippus changed this, using five spheres for the Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, and Mars, and four for Jupiter and Saturn. This made 33 spheres. Each planet was attached to the innermost sphere in its own set. These models described planet movements well, but they weren't perfectly accurate for predicting exact positions.

Aristotle (in the 300s BC) built on Eudoxus's ideas to create a physical model of the universe. In his model, the spherical Earth was at the center. Planets were moved by 47 or 55 connected spheres. These spheres were made of an unchanging fifth element called aether. Aristotle believed each sphere was moved by its own god, an "unmoved mover," who moved the sphere simply by being loved by it.

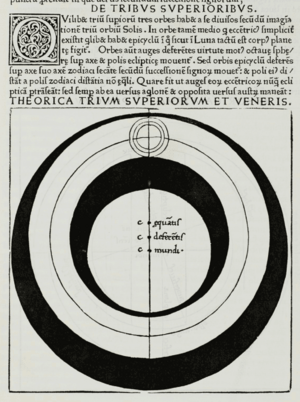

The astronomer Ptolemy (around 150 AD) created detailed models to predict star and planet movements. He used eccentrics (off-center circles) and epicycles (circles within circles). This made his model more accurate than earlier ones. In Ptolemy's physical model, each planet was inside two or more spheres. One sphere was the main path (the deferent), slightly off-center from Earth. The other was an epicycle, a smaller circle embedded in the deferent, with the planet on it. Ptolemy's model gave the size of the universe. He thought Saturn was almost 20,000 times the Earth's radius away, and the fixed stars were at least 20,000 Earth radii away.

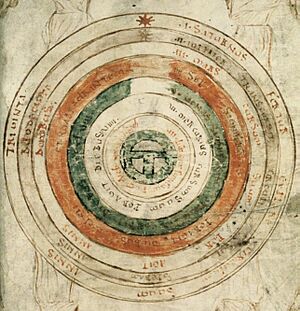

The planetary spheres were arranged outwards from the stationary Earth at the center. The order was: Moon, Mercury, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Beyond these were the stars. Some scholars added more spheres to explain other movements, like the slow wobble of Earth's axis. In ancient times, the order of Mercury and Venus wasn't always agreed upon. Ptolemy put them both below the Sun, with Venus above Mercury.

The Middle Ages

Astronomical Ideas

Many astronomers, starting with al-Farghānī (in the 800s), used Ptolemy's model to calculate distances to stars and planets. Al-Farghānī calculated the distance to the stars as over 20,000 Earth radii. If Earth's radius was about 3,250 miles (5,230 km), this meant the stars were over 65 million miles (105 million km) away. Other astronomers like Al-Battānī made their own calculations, finding similar distances.

Around 1000 AD, the Arab astronomer Ibn al-Haytham (Alhacen) further developed Ptolemy's models using nested spheres. He even suggested that celestial spheres were not made of solid matter.

Later, in the 1100s, al-Bitrūjī tried to explain planet movements using only concentric spheres, without Ptolemy's epicycles. His model was less accurate for predictions but was discussed by others.

In the 1200s, al-'Urḍi made big changes to Ptolemy's system. He recalculated distances and placed Venus's sphere above the Sun's. His model put the stars' sphere over 140,000 Earth radii away.

Around the same time, scholars in European universities started studying Aristotle and Ptolemy again. They used the nested sphere model to figure out the size of the universe. Campanus of Novara calculated the distance to the planets as over 22,000 Earth radii. Roger Bacon cited Al-Farghānī's distance to the stars. People truly believed this model. For example, Bacon wrote about how long it would take to walk to the Moon. A popular story said it would take 8,000 years to reach the highest starry heaven!

Discussions about the Spheres

Philosophers cared more about what the spheres were made of and what made them move.

Some Islamic scholars debated if celestial spheres were real, solid bodies or just imaginary circles. Most learned people and astronomers thought they were solid spheres. But some, like Dahhak, thought they were abstract.

Christian and Muslim philosophers added an outermost region, the empyrean heaven. This was seen as the home of God and angels. Medieval Christians often linked the sphere of stars to the Biblical firmament.

Most medieval scholars thought celestial spheres were continuous, like a fluid, rather than hard.

Later, some thinkers like Adud al-Din al-Iji (1281–1355) said celestial spheres were "imaginary things" and "more tenuous than a spider's web." But others disagreed, saying they were real even if not physically solid.

People had many ideas about what made the spheres move. Some thought it was the material they were made of. Others thought it was external movers, like special intelligences or angels. By the end of the Middle Ages, many in Europe believed that angels moved the celestial bodies. The outermost sphere, which caused the daily motion of everything below it, was moved by a "Prime Mover," identified with God. Each lower sphere was moved by a lesser spiritual mover, called an intelligence.

The Renaissance

In the early 1500s, Nicolaus Copernicus changed astronomy by putting the Sun at the center of the universe instead of Earth. His famous book was called De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres). Copernicus didn't go into much detail about the spheres' physical nature, but he seemed to believe they were not solid. He removed some spheres and placed the Moon's orb around Earth. The planets orbited the Sun in this order: Mercury, Venus, the large orb containing Earth and the Moon, then Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. He kept the eighth sphere for the stars, believing it was still.

An English almanac maker, Thomas Digges, drew the new Copernican system in 1576. He arranged the "orbs" in the new order. He expanded one sphere to carry Earth, its elements, and the Moon. He also made the sphere of stars infinitely large to hold all stars and serve as "the court of the Great God."

In the 1500s, some thinkers started to abandon the idea of celestial spheres. Christoph Rothmann argued that observations of a comet in 1585 showed it was beyond Saturn. Also, the lack of light bending suggested the celestial region was like air, meaning there were no solid planetary spheres.

Tycho Brahe's studies of comets from 1577 to 1585 also led him to believe that "the structure of the heavens was very fluid and simple." He disagreed with many who thought the heavens were made of "hard and impervious matter."

In his early work, Mysterium Cosmographicum, Johannes Kepler looked at the distances between planets in the Copernican system. He filled the large gaps between the planetary spheres with the five Platonic polyhedra (special geometric shapes). In Kepler's later work, the spheres were just the geometric spaces where planets orbited, not physical, spinning orbs. The Sun, which he thought had a "motive soul," caused the planets to move. However, an unmoving starry sphere was still part of Kepler's view of the cosmos.

Spheres in Art and Stories

In Cicero's Dream of Scipio, a character describes rising through the celestial spheres. From up there, Earth and the Roman Empire seemed tiny. A book by Macrobius explaining Cicero's Dream helped spread the idea of celestial spheres in the Early Middle Ages.

Some medieval thinkers noted that the physical order of the spheres was opposite to their spiritual order. In the spiritual view, God was at the center, and Earth was at the edge. In the early 1300s, Dante, in his Divine Comedy, described God as a light at the center of the cosmos. He wrote about ascending beyond physical existence to the highest Heaven, where he met God. Later, in a book by Nicole Oresme (1377), the spheres were drawn in the usual order (Moon closest, stars highest). But they were drawn curving upwards, centered on God, not curving downwards, centered on Earth. Below this drawing, Oresme quoted the Psalms: "The heavens declare the Glory of God."

The Portuguese epic poem The Lusiads (late 1500s) describes the celestial spheres as a "great machine of the universe" built by God. The explorer Vasco da Gama is shown the spheres as a mechanical model. Unlike Cicero's story, da Gama's tour starts from the highest Heaven and moves inward toward Earth. This shows the importance of human actions in God's plan.

See also

- Angels in Christianity

- Body of light

- History of the center of the Universe

- Musica universalis

- Primum Mobile

- Seven heavens

- Sphere of fire

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |