Tycho Brahe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tycho Brahe

|

|

|---|---|

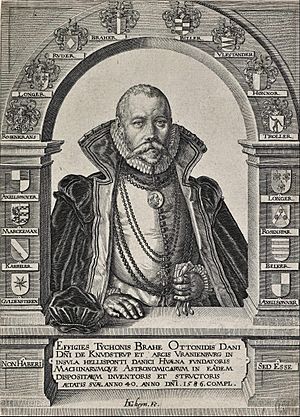

Portrait of Tycho c. 1596

|

|

| Born |

Tyge Ottesen Brahe

14 December 1546 Knutstorp Castle, Scania, Denmark–Norway

|

| Died | 24 October 1601 (aged 54) |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Alma mater | University of Copenhagen Leipzig University University of Rostock |

| Occupation | Astronomer, writer |

| Known for | Tychonic system Tycho's supernova Rudolphine Tables Variation |

| Spouse(s) | Kirsten Barbara Jørgensdatter |

| Children | 8 |

| Parent(s) | Otte Brahe Beate Clausdatter Bille |

| Signature | |

|

|

Tycho Brahe (born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho) (14 December 1546 – 24 October 1601) was a famous Danish astronomer. He was known for making very detailed and accurate observations of the sky. During his life, people knew him as an astronomer, an astrologer, and an alchemist. He was the last major astronomer before the telescope was invented.

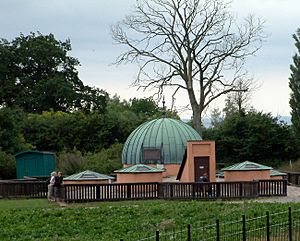

In 1572, Tycho saw a brand-new star that was brighter than any other star or planet. He was amazed because stars were not supposed to change. This made him want to build better tools to measure the sky. King Frederick II gave Tycho land on the island of Hven. He also gave him money to build Uraniborg, the first big observatory in Christian Europe. Later, he worked underground at Stjerneborg because his tools at Uraniborg were not steady enough. His amazing research helped turn astronomy into a modern science. It also helped start the Scientific Revolution.

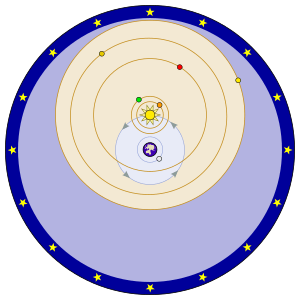

Tycho came from important noble families and had a good education. He tried to combine the ideas of Copernican heliocentrism (Earth orbits the Sun) with the older Ptolemaic system (Earth is the center). He created his own model of the Universe, called the Tychonic system. In his model, the Sun orbited the Earth, and the other planets orbited the Sun. In his book De nova stella (1573), he showed that the sky was not unchanging, as people had believed for a long time. His measurements proved that "new stars" (now called supernovae) were far beyond the Moon. He also showed that comets were not just weather in the atmosphere, as people used to think.

In 1597, the new king, Christian IV, made Tycho leave Denmark. He was invited to Prague, where he became the official astronomer for the emperor. He built another observatory there. Before he died in 1601, Johannes Kepler helped him for a year. Kepler later used Tycho's data to figure out his own three laws of planetary motion.

Contents

Tycho Brahe: A Life Among the Stars

Early Life and Learning

Tycho Brahe was born on December 14, 1546. His family lived at Knutstorp Castle in what was then Danish Scania. He was the oldest of 12 children. Only 8 of them lived to be adults.

When he was two years old, his uncle Jørgen Thygesen Brahe and his wife Inger Oxe raised him. They did not have children of their own. Tycho later wrote that his uncle treated him like his own son. His uncle also made him his heir.

From ages 6 to 12, Tycho went to Latin school. At 12, in 1559, he started studying at the University of Copenhagen. His uncle wanted him to study law. But Tycho became very interested in astronomy. He learned about Aristotelian physics and how people thought the Universe worked.

He saw a solar eclipse in 1560. He was amazed that it had been predicted, even though the prediction was a day off. He realized that better observations were needed to make more exact predictions. He bought books about astronomy.

In 1562, Tycho's uncle sent him on a study trip in Europe. Tycho was 15 years old. He convinced his mentor, Anders Sørensen Vedel, to let him study astronomy during the trip. In 1563, he saw Jupiter and Saturn come very close together. He noticed that the tables used to predict this event were not accurate. This made him realize that astronomy needed careful, regular observations. He started keeping detailed notes of everything he saw in the sky.

A New Nose!

In 1566, Tycho went to study at the University of Rostock. He also became interested in alchemy and herbal medicine. On December 29, 1566, when he was 20, Tycho lost part of his nose. This happened during a sword duel with another nobleman. They had argued about who was a better mathematician.

Tycho got the best medical care. He wore a fake nose for the rest of his life. It was held on with glue. People thought it was made of silver and gold. But in 2012, scientists found that it was likely made of brass. He probably saved his gold and silver noses for special events.

Science and Life on Hven Island

In 1567, Tycho came home. He wanted to be an astronomer. His family supported his choice, even though they expected him to go into law. An uncle, Steen Bille, helped him build an observatory and a lab for alchemy. King Frederick II noticed Tycho's work. The King offered him the island of Hven and money to build an observatory there. This was the first large observatory in Christian Europe.

Marriage and Family Life

In 1571, Tycho fell in love with Kirsten Jørgensdatter. She was a commoner, not from a noble family. Tycho could not formally marry her without losing his noble rights. But Danish law allowed them to live together as husband and wife. After three years, their union became a legal marriage. However, their children would be considered commoners.

Kirsten and Tycho had eight children together. Six of them lived to be adults. Their first daughter, Kirstine, was born in 1573. She died from the plague in 1576. Tycho wrote a sad poem for her tombstone.

A New Star in the Sky

On November 11, 1572, Tycho saw a very bright new star. It appeared in the constellation Cassiopeia. People at that time believed the sky beyond the Moon never changed. Other observers thought this new star was just something in Earth's atmosphere.

But Tycho observed that the star did not move against the background of other stars. This meant it was much farther away than the Moon or planets. He also saw that it stayed in the same place for months. This showed it was not a planet, but a fixed star. In 1573, he published a book called De nova stella. This book gave the name "nova" (new) to such stars. Today, we call this star a supernova. We know it is 7,500 light-years from Earth. This discovery helped him choose astronomy as his life's work. His book made him famous among scientists in Europe.

Building a Star Castle

Tycho kept making detailed observations. His younger sister, Sophie, often helped him. In 1576, the King offered Tycho the island of Hven and money to build an observatory. Tycho had planned to move to another city, but the King wanted to keep him in Denmark.

Tycho became the feudal lord of Hven. He took charge of farming and asked the farmers to work more. The farmers complained about his taxes and labor demands. But a court ruled that Tycho had the right to collect taxes and labor.

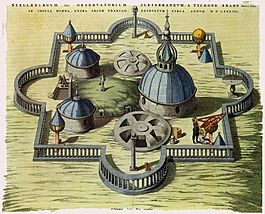

Tycho designed his castle, Uraniborg, as a place for arts and sciences. It was named after Urania, the muse of astronomy. Construction began in 1576. It also had a lab for his alchemy experiments in the cellar. Uraniborg was one of the first buildings in northern Europe to show Italian Renaissance style.

Tycho realized that the towers of Uraniborg were not good enough for observations. The instruments were exposed to weather and the building moved. So, in 1584, he built an underground observatory called Stjerneborg (Star Castle) near Uraniborg. It had several underground rooms for his large instruments.

Uraniborg also had an alchemy lab with 16 furnaces. Tycho made it a research center. Almost 100 students and workers were there from 1576 to 1597. He also had a printing press and a paper mill. These were among the first in Scandinavia. This allowed him to print his own books.

He observed the great comet that appeared from November 1577 to January 1578. People believed comets were signs of bad things to come. Tycho found that the comet was much farther away than the Moon. This proved that comets were not in Earth's atmosphere. He also noticed that the comet's tail always pointed away from the Sun.

Tycho received a lot of money from the King. He often held big parties at his castle. Many important people visited Hven, including James VI of Scotland.

As part of his duties, Tycho also worked as a royal astrologer. Each year, he gave the court an Almanac. It predicted how the stars would affect the year. He also made horoscopes for princes when they were born.

Sharing Ideas and Debates

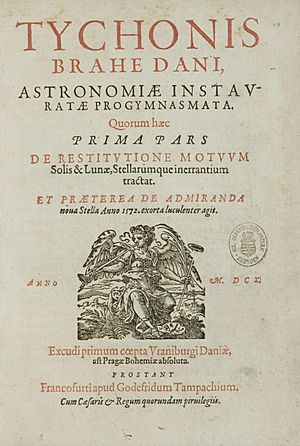

In 1588, King Frederick died. Tycho published part of his big work, Astronomiae Instauratae Progymnasmata (Introduction to the New Astronomy). The first part, about the new star of 1572, was not finished until after his death. The second part, about the 1577 comet, was printed at Uraniborg in 1588. It also included Tycho's model of the world.

Tycho wrote letters to scientists all over Europe. He asked about their observations and shared his own ideas. This helped spread new scientific knowledge. He also had some arguments with people who disagreed with his theories. One argument was with John Craig, who believed in the old ideas of Aristotle. Craig did not accept that the 1577 comet was far away in space.

Leaving Denmark

When King Frederick died in 1588, his son Christian IV was only 11. A group of people ruled until the new king was old enough. The head of this group, Christoffer Valkendorff, did not like Tycho. So, Tycho's influence at the Danish court became less.

Tycho realized the young king was more interested in war than in science. He also knew the king might not keep his father's promise about Hven. King Christian IV wanted to reduce the power of noble families. Tycho was one of the nobles who lost favor with the new king.

Tycho left Hven in 1597. He took some of his instruments with him. Before leaving, he finished his star catalog, which listed the positions of 1,000 stars. He tried to get the king to let him come back, but it did not work. He wrote a famous poem, Elegy to Dania, where he criticized Denmark for not valuing his genius. His book Astronomiae instauratae mechanica (1598) showed and described his instruments.

From 1597 to 1598, he stayed with a friend in Germany. In 1599, Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor invited him to Prague. Tycho became the Imperial Court Astronomer. He built a new observatory there. At the imperial court, Tycho's wife and children were treated like nobles, which had not happened in Denmark.

Working with Kepler

In Prague, Tycho worked closely with Johannes Kepler. Kepler was his assistant. Kepler believed the Earth orbited the Sun, which was different from Tycho's view. They worked together on a new star catalog called the Rudolphine Tables. This catalog was based on Tycho's very accurate observations.

Kepler respected Tycho's methods and the accuracy of his observations. He saw Tycho as a new Hipparchus, who would help restart the science of astronomy.

Illness and Death

Tycho suddenly became sick after a party in Prague. He died eleven days later, on October 24, 1601, at age 54. Before he died, he often said he hoped he had not lived in vain. He asked Kepler to finish the Rudolphine Tables. He also hoped Kepler would use Tycho's own model of the planets.

Doctors at the time thought he died from a kidney stone. But when his body was examined in 1901, no kidney stones were found. Modern doctors think he might have died from a burst bladder or other issues that caused waste to build up in his body.

Tycho is buried in the Church of Our Lady before Týn in Old Town Square in Prague.

Observing the Heavens

How Tycho Observed the Sky

Tycho loved making accurate observations. He spent his life trying to improve tools for measurement. He was the last major astronomer to work without a telescope. Galileo Galilei and others would use telescopes soon after.

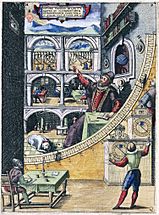

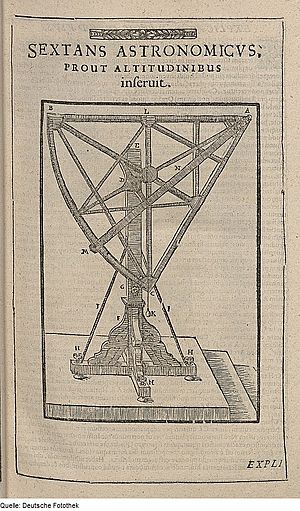

Tycho focused on making better versions of existing tools, like the sextant and the quadrant. He designed larger versions of these tools to get more accurate results. He realized that wind and building movements affected his tools. So, he put his instruments underground, directly on solid rock.

Tycho's observations of stars and planets were known for being both accurate and many. His measurements were much more precise than anyone before him. They were about five times more accurate than other astronomers of his time. He aimed for his measurements to be within one arcminute of the true positions.

One of Tycho's most important ideas was to correct for how light bends when it passes through Earth's atmosphere. This bending makes objects appear higher in the sky than they really are. He created the first tables to fix this error.

To do all the math for his astronomical data, Tycho used a new method called prosthaphaeresis. This method helped him multiply numbers using trigonometric formulas. It was used before logarithms were invented.

Tycho's Instruments

Tycho made many of his own instruments. He started making better tools when he was a student. He realized he needed a better way to record his observations, angles, and descriptions. He started using a special notebook for this. In it, he drew what he saw, like comets and planet movements.

After school, he used his inheritance to build new instruments. He made a quadrant that was 39 centimeters wide. He added a new type of sight called a pinnacidia. This new sight was much better than old pinhole sights. It helped him get more accurate measurements.

Tycho also built instruments for specific events. For example, in 1577, he saw a comet. He used a large brass azimuthal quadrant to observe it. This tool helped him track the comet's path and distance. It showed that the comet crossed the orbits of the solar system's planets.

Many more instruments were built at Uraniborg, Tycho Brahe's home and observatory. Some of these tools were very large. For example, he had a steel azimuth quadrant that was six feet (194 centimeters) wide. These large instruments were placed in the two observatories at Uraniborg.

Tycho's Big Idea: The Universe Model

Tycho admired Nicolaus Copernicus, who said the Earth orbits the Sun. But Tycho could not agree with Copernicus's idea because it went against the basic rules of physics that people believed at the time. He also thought Copernicus's observations were not accurate enough.

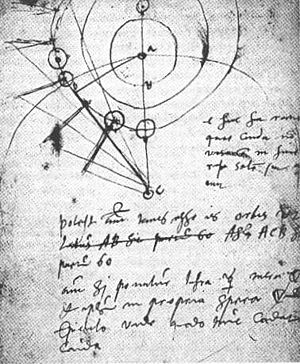

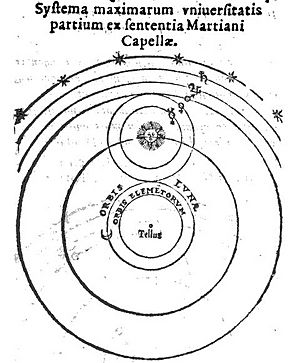

Instead, Tycho suggested his own "geo-heliocentric" system. In this model, the Sun and Moon orbited the Earth. But the other planets orbited the Sun. His system had many of the same benefits as Copernicus's system for observations and calculations. It was a good option for astronomers who did not like older models but did not want to fully accept the Sun-centered idea.

Tycho's system had a big new idea: it got rid of the old belief in transparent, rotating crystal spheres that carried the planets. He believed that if the Earth moved around the Sun, we should see a small shift in the positions of stars every six months. This is called stellar parallax. Since he could not see this shift, he believed the Earth must be still.

He also thought that if stars were as far away as Copernicus's model suggested, they would have to be incredibly huge. They would be bigger than the Earth's orbit, and much larger than the Sun. To Tycho, this seemed impossible. However, some people who believed in Copernicus said that God could make stars as big as He wanted.

Tycho also used religious reasons for his Earth-centered view. He said that holy writings showed the Earth was at rest. But he mostly focused on scientific arguments over time.

Tycho's model was different from other similar models. In his model, the orbits of Mars and the Sun crossed each other. This meant there could be no solid, rotating spheres in the sky. This idea was also supported by his observation that the 1577 comet passed through where these spheres were thought to be.

Lunar Theory

Tycho made important discoveries about the Moon's movement. He found that the Moon's longitude changes in a way called "variation." He also found that the Moon's orbit around Earth wobbles. These discoveries greatly improved how well people could predict the Moon's position. His ideas about the Moon were published after his death by Kepler in 1602.

Later Astronomy Developments

Kepler used Tycho's detailed records of Mars's movement. From this, Kepler figured out his laws of planetary motion. These laws allowed for very accurate calculations of astronomical tables. This strongly supported the idea of a Sun-centered Solar System.

In 1610, Galileo used a telescope to see that Venus showed all the same phases as the Moon. This proved that the old Earth-centered Ptolemaic model was wrong. After this, many astronomers in the 17th century used models like Tycho's. These models could explain Venus's phases without needing a moving Earth.

Tycho's model was very popular, especially in Catholic countries. It offered a way to combine old and new ideas safely. However, in Germany, the Netherlands, and England, Tycho's system became less common much earlier.

In 1729, James Bradley discovered stellar aberration. This finally showed direct proof that the Earth moves around the Sun. Stellar aberration could only be explained if the Earth was orbiting the Sun.

Work in Medicine, Alchemy, and Astrology

Tycho also worked in medicine and alchemy. He was inspired by a doctor named Paracelsus. This doctor believed that the human body was affected by celestial bodies. Tycho used his herb garden at Uraniborg to make herbal medicines. He used them to treat fevers and the plague. His herbal medicines were used until the late 1800s.

The term Tycho Brahe days referred to "unlucky days" in old calendars. But these days have no direct link to Tycho or his work. Tycho did not always publicize his own astrology work. Some people think he might have lost faith in astrology over time. Others think he just changed how he talked about it. He might have worried that connections to astrology would hurt how his astronomy work was seen.

Tycho's Legacy

Biographies and Studies

The first book about Tycho's life was written in 1654. It was also the first full book about any scientist. For a long time, people saw Tycho as someone who did not want to accept the new ideas of Copernicus. They mostly valued his observations because they helped Kepler.

But in the second half of the 20th century, scholars started to look at his importance differently. They showed that Tycho admired Copernicus. However, he could not make Copernicus's ideas fit with the physics he believed in. Studies also showed that Uraniborg was a training center for many scientists.

Scientific Impact

Even though Tycho's model of the planets was soon replaced, his observations were a huge step forward for the scientific revolution. People often see Tycho as someone who focused on precise and objective measurements. This idea came from early books about him.

The Tycho Brahe Prize started in 2008. It is given each year by the European Astronomical Society. It honors people who develop or use European astronomical instruments, or make big discoveries using them.

Cultural Impact

Tycho's discovery of the new star inspired Edgar Allan Poe's poem "Al Aaraaf". Some people also believe that Tycho's supernova is the "star that's westward from the pole" in Shakespeare's play Hamlet.

The lunar crater Tycho is named after him. So is the crater Tycho Brahe on Mars. A small planet in the asteroid belt is also named 1677 Tycho Brahe. The bright supernova, SN 1572, is known as Tycho's Nova. The Tycho Brahe Planetarium in Copenhagen is also named after him. The palm tree genus Brahea is also named in his honor.

Brahe Rock in Antarctica is named after Tycho Brahe.

In the book and TV series The Expanse, "Tycho" is the name of a company known for building large structures in space. They have their own space station called "Tycho Station."

Works (selection)

- De Mundi Aetherei Recentioribus Phaenomenis Liber Secundus (Uraniborg, 1588; Prague, 1603; Frankfurt, 1610)

- Tychonis Brahe Astronomiae Instauratae Progymnasmata (Prague, 1602/03; Frankfurt, 1610)

- (in la) [Opere. Carteggi]. København: G.E.C. Gad. 1876–1886. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=4296228.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Tycho Brahe para niños

In Spanish: Tycho Brahe para niños

- December 1573 lunar eclipse

- History of trigonometry

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |