Copernican heliocentrism facts for kids

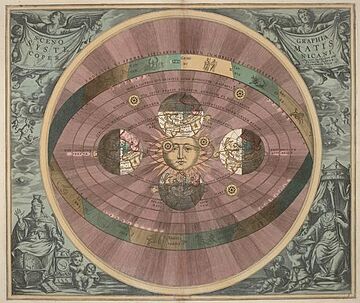

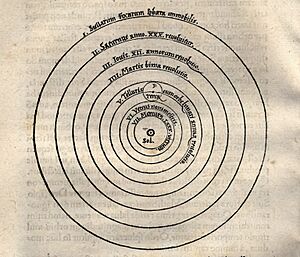

Copernican heliocentrism is a scientific idea about our Universe. It was created by Nicolaus Copernicus and shared in 1543. This model placed the Sun at the center of the Universe. It said the Sun stayed still, while Earth and the other planets moved around it. They orbited in circular paths, using smaller circles called epicycles, and moved at steady speeds.

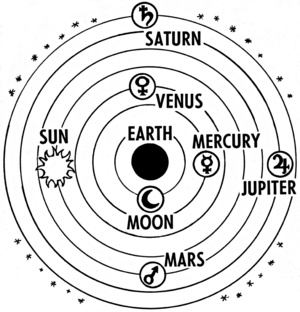

Copernicus's idea replaced the geocentric model of Ptolemy. That older model had been popular for hundreds of years. It placed Earth at the very center of the Universe.

Copernicus shared his ideas with friends before 1514. But he only decided to publish them later, after his student Rheticus encouraged him. Copernicus wanted to show a better way to understand the cosmos. He aimed to figure out the length of a solar year more accurately. His model kept some older ideas, like planets moving in perfect circles. But it also introduced new ones:

- Earth is one of many planets orbiting a still Sun.

- Earth moves in three ways: it spins daily, orbits the Sun yearly, and its axis tilts each year.

- The strange "backward" motion of planets is explained by Earth's own movement.

- The distance from Earth to the Sun is tiny compared to the distance to the stars.

Contents

Early Ideas About the Universe

Ancient Thinkers

Long ago, in the 300s BCE, a thinker named Philolaus suggested that Earth might move. Later, in the 200s BCE, Aristarchus of Samos came up with the first serious model of a heliocentric (Sun-centered) Solar System. He built on ideas that Earth spins on its axis every 24 hours.

Even though his original writings are lost, Archimedes wrote about Aristarchus's ideas. Archimedes explained that Aristarchus believed the Sun and stars stayed still. He thought Earth revolved around the Sun in a circle, with the Sun in the middle.

Some people mistakenly think Aristarchus's Sun-centered view was rejected by everyone back then. This idea comes from a mistranslation of an old text. It made it seem like Aristarchus was accused of being disrespectful for his ideas. But this was not the case.

Ptolemy's Earth-Centered System

For about 1,400 years, the main idea about the cosmos in Europe was the Ptolemaic System. This was a geocentric model, meaning Earth was at the center. It was created by Ptolemy around 150 CE. His book, Almagest, was the most important astronomy text for a long time.

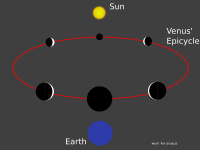

In Ptolemy's system, Earth was still and at the center. Stars were fixed on a large outer sphere that spun quickly. Planets were on smaller spheres between Earth and the stars. To explain why planets sometimes seemed to move backward (called apparent retrograde motion), Ptolemy used epicycles. This meant a planet moved in a small circle (the epicycle) while the center of that small circle moved in a larger circle (the deferent) around Earth.

Ptolemy also added something called the equant. This was a point from which a planet's epicycle seemed to move at a steady speed. But this point was not exactly at the center of the planet's main orbit. This idea broke a rule that all planet motions should be perfectly circular and steady. Many astronomers in the Middle Ages saw this as a problem.

Indian and Islamic Astronomers

Around 499 CE, the Indian astronomer Aryabhata suggested that Earth spins on its axis. He said this spinning caused the stars to appear to move westward. He also thought that planet orbits were oval-shaped.

Later, several Islamic astronomers questioned if Earth was truly still and at the center. Some, like Al-Sijzi, believed Earth rotated. They thought the sky's movement was actually due to Earth's motion. In the 12th century, Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji offered a different system, though it was not Sun-centered. He said Ptolemy's model was good for predicting, but not real.

From the 1200s to 1400s, Arab and Persian astronomers like Nasir al-Din al-Tusi and Ibn al-Shatir developed mathematical methods for Earth-centered models. These methods were very similar to some that Copernicus later used in his Sun-centered models.

Copernicus's Theory

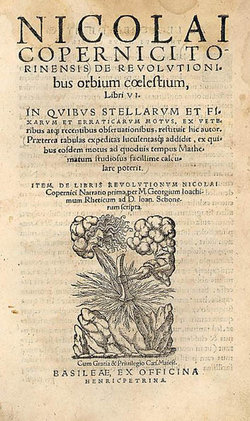

Copernicus's most important book was De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, which means On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres. It was published in 1543, the year he died. This book marked the start of a big change. It moved away from the idea of an Earth-centered universe.

Copernicus believed Earth was just another planet. He said it revolved around the Sun once a year and spun on its axis once a day. While he put the Sun near the center of the celestial spheres, he didn't put it at the exact center of the whole Universe. Copernicus's system used only steady circular motions. This fixed what many saw as a flaw in Ptolemy's system.

Copernicus's model actually used more epicycles than Ptolemy's. This was because he used 1,500 years of Ptolemy's data to make his own estimates more accurate.

Here are the main ideas of Copernicus's theory:

- Heavenly motions are smooth, never-ending, and circular, or made of several circles.

- The center of the Universe is close to the Sun.

- Around the Sun, in order, are Mercury, Venus, the Earth (with its Moon), Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and then the fixed stars.

- Earth has three movements: it spins daily, orbits the Sun yearly, and its axis tilts each year.

- The "backward" motion of planets is explained by Earth's own movement.

- The distance from Earth to the Sun is small compared to the distance to the stars.

Copernicus got his ideas not just from observing planets. He also read old authors like Cicero and Plutarch. These writers mentioned ancient Greek thinkers who believed Earth moved, though not necessarily around the Sun. Copernicus even mentioned Aristarchus and Philolaus in an early draft of his book. He noted that they believed in Earth's movement.

Copernicus used mathematical tools that were also found in earlier Arabic writings. For example, the way he replaced the equant with two epicycles was similar to a method used by al-Shatir. This has led some experts to think Copernicus might have seen some of these earlier works. However, no direct proof of this has been found. Still, Copernicus did mention some Islamic astronomers in his book, whose ideas and observations he used.

About De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

When Copernicus's book was published, it had an extra, unsigned introduction. This was added by a friend, Andreas Osiander. Osiander wrote that Copernicus's Sun-centered idea was just a mathematical guess, not necessarily the truth. This was likely done to avoid religious problems. At the time, some thought the idea went against the Old Testament (like the story in Joshua 10:12-13 about the Sun standing still). But there's no sign that Copernicus himself saw his model as just a guess.

Copernicus's actual book started with a letter from his friend, Nikolaus von Schönberg. He encouraged Copernicus to publish his theory. In a long introduction, Copernicus dedicated the book to Pope Paul III. He explained that he wrote it because earlier astronomers couldn't agree on a good theory of planets. He also noted that if his system made predictions more accurate, it would help the Church create a better calendar. At that time, improving the Julian Calendar was important to the Church.

The book itself is divided into six parts:

- The first part gives a general overview of the Sun-centered theory.

- The second part explains the basics of spherical astronomy and lists stars.

- The third part focuses on the Sun's apparent movements.

- The fourth part describes the Moon and how it moves.

- The fifth part explains the new system for planetary longitude.

- The sixth part further explains the new system for planetary latitude.

Early Reactions to Copernicus's Ideas

After De Revolutionibus was published, not many astronomers were convinced by Copernicus's system until about 1700. Even though many copies of the book were made, few people believed Earth actually moved. Even 45 years after the book came out, a famous astronomer named Tycho Brahe created a similar model. But he kept Earth fixed at the center instead of the Sun. It took another generation for astronomers to truly accept the Sun-centered view.

For people at the time, Copernicus's ideas didn't seem much easier to use than the Earth-centered theory. They also didn't make predictions of planet positions much more accurate. Copernicus knew this. He couldn't offer direct proof from observations. Instead, he argued that his system was more complete and elegant. The Copernican model also seemed to go against common sense and the Bible.

Tycho Brahe, one of the best astronomers of his time, understood the beauty of Copernicus's system. But he disagreed with the idea of a moving Earth for several reasons. The science of the time (called Aristotelian physics) couldn't explain how a huge body like Earth could move. It was thought that heavenly bodies were made of a special substance called aether that moved naturally. Tycho said that Copernicus's system "ascribes to the Earth, that hulking, lazy body, unfit for motion, a motion as quick as that of the aethereal torches, and a triple motion at that."

The Copernican Revolution

The Copernican Revolution was a huge shift in how people understood the heavens. It moved from the Ptolemaic system (Earth at the center) to the heliocentric model (Sun at the center of the Solar System). This change took over a century. It started with Copernicus's book and ended with the work of Isaac Newton.

While Copernicus's ideas weren't immediately popular, they greatly influenced later scientists. Galileo and Johannes Kepler adopted and improved them. Kepler, using detailed observations by Tycho Brahe, discovered that Mars's orbit was an ellipse (an oval shape), not a perfect circle. He also found that its speed changed depending on its distance from the Sun. He wrote about this in his 1609 book, Astronomia nova.

During the 1600s, more discoveries helped people accept the Sun-centered model:

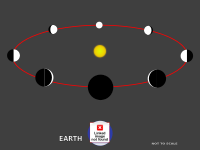

- In 1610, Galileo used the new telescope. He discovered the four large moons of Jupiter. This showed that some bodies in the Solar System did not orbit Earth. He also saw the phases of Venus, which were better explained by Venus orbiting the Sun.

- In 1639, Giovanni Zupi saw the phases of Mercury with a telescope.

- In 1687, Isaac Newton explained Kepler's elliptical orbits. He did this with his idea of universal gravity.

Modern Views

Why Copernicus Was Right

From today's perspective, Copernicus's model has many good points. He clearly explained why we have seasons: because Earth's axis is tilted, not straight up and down, compared to its orbit.

Also, Copernicus's theory gave a simple explanation for the planets' apparent "backward" motions. This happens because Earth is also moving around the Sun. In the Sun-centered model, these backward motions are a natural result of how planets orbit. In the Earth-centered model, they needed complicated epicycles that seemed mysteriously linked to the Sun's movement.

How Historians See It Now

Historians of science have debated if Copernicus's ideas were truly "revolutionary" or more "conservative." Some, like Arthur Koestler, suggested Copernicus was afraid to publish his work. Others, like Thomas Kuhn, argued that Copernicus only shifted some features from Earth to the Sun.

However, many historians now believe Kuhn underestimated how "revolutionary" Copernicus's work was. They point out how difficult it must have been for Copernicus to propose a new astronomical theory based mainly on simpler geometry, especially since he had no experimental proof at the time.

See also

- Copernican principle

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |