Arthur Koestler facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Arthur Koestler

|

|

|---|---|

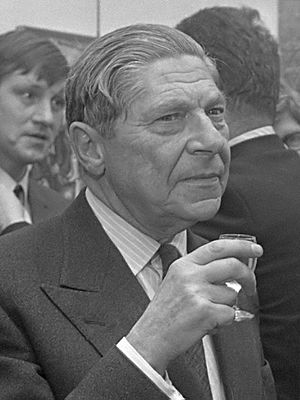

Koestler in 1969

|

|

| Born | Kösztler Artúr 5 September 1905 Budapest, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 1 March 1983 (aged 77) London, United Kingdom |

| Occupation | Novelist, essayist, journalist |

| Education | University of Vienna |

| Period | 1934–1983 |

| Subject | Fiction, non-fiction, history, autobiography, politics, philosophy, psychology, parapsychology, science |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse |

|

Arthur Koestler (born Kösztler Artúr; 5 September 1905 – 1 March 1983) was a famous author and journalist. He was born in Budapest, Hungary, and grew up mostly in Austria. In 1931, Koestler joined the Communist Party of Germany. However, he left in 1938 because he disagreed with Stalinism, a strict form of communism.

In 1940, he moved to Britain and published his novel Darkness at Noon. This book was against totalitarian governments, which control every part of people's lives. The novel made him famous around the world. For the next 43 years, Koestler supported many different ideas and wrote many books. These included novels, memoirs (life stories), biographies (stories of other people's lives), and essays (short writings on a topic).

In 1968, he won the Sonning Prize for his "outstanding contribution to European culture." In 1972, he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE). This is a special award from the British Queen or King.

In 1976, he was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, which affects movement. In 1979, he was diagnosed with terminal leukaemia, a serious blood cancer. Arthur Koestler and his wife Cynthia died at their London home on 1 March 1983.

Contents

- Arthur Koestler's Early Life

- Adventures as a Young Journalist

- Koestler's Life in the 1930s

- World War II and Beyond

- Post-War Years and Later Life

- Koestler's Impact and Ideas

- Working with the Information Research Department

- Languages Koestler Spoke

- Famous Quotes

- Published Works

- Images for kids

- See also

Arthur Koestler's Early Life

Family Background and Childhood

Arthur Koestler was born in Budapest to Jewish parents, Henrik and Adele Koestler. His father, Henrik, learned English, German, and French by himself. He became a successful businessman, importing textiles.

Arthur's mother, Adele, came from a well-known Jewish family in Prague. Her ancestors included famous doctors and poets. Adele's family moved to Vienna, but faced financial problems. Her father left for the United States, and Adele and her mother moved to Budapest.

Henrik and Adele married in 1900, and Arthur, their only child, was born in 1905. The Koestlers lived in nice apartments in Budapest and had a cook and a governess. Arthur started school at a special private kindergarten.

War and Moving to Vienna

When World War I began in 1914, his father's business failed. The family moved to Vienna for a short time. After the war, they returned to Budapest.

In 1919, Koestler and his family supported the Hungarian Soviet Republic, a short-lived communist government. Even though his father's factory was taken over by the government, his father was made its director and paid well. Koestler later wrote about his teenage hopes for a better future during this time.

After the communist government fell, the Koestlers saw the Romanian Army occupy Budapest. Then came the White Terror, a period of violence by a right-wing government. In 1920, the family moved back to Vienna, where Henrik started a new successful business.

University and Leaving for Palestine

In September 1922, Arthur started studying engineering at the University of Vienna. He joined a Zionist student group. When his father's business failed again, Koestler stopped attending lectures and was expelled.

In March 1926, he told his parents he was going to Mandate Palestine for a year. He wanted to work as an engineer to gain experience. On 1 April 1926, he left Vienna for Palestine.

Adventures as a Young Journalist

Life in Palestine and Berlin

For a few weeks, Koestler lived in a kibbutz, a community farm, but he was not accepted as a full member. For the next year, he worked odd jobs in Haifa, Tel Aviv, and Jerusalem. He was often poor and hungry, relying on friends. He sometimes wrote for local newspapers in German.

In early 1927, he went to Berlin and worked for Ze'ev Jabotinsky's Revisionist Party. Later that year, Koestler became a Middle East reporter for the important Berlin-based Ullstein-Verlag newspaper group. He returned to Jerusalem and wrote detailed political articles. He traveled widely, interviewing leaders like kings and presidents. This helped him become a well-known journalist. He realized he would not fit into Palestine's Jewish community or have a career writing in Hebrew.

Reporting from Paris and a Polar Flight

In June 1929, Koestler moved to Paris to work for the Ullstein News Service. In 1931, he was called to Berlin and became the science editor for the Vossische Zeitung newspaper. He also became a science advisor for the Ullstein newspaper empire.

In July 1931, Ullstein chose him to report from the Graf Zeppelin airship's week-long polar flight. Koestler was the only journalist on board. His live radio broadcasts and articles made him even more famous. Soon after, he became a foreign editor for the Berliner Zeitung am Mittag.

In 1931, Koestler became a supporter of Marxism-Leninism, a type of communism. He was impressed by the Soviet Union's achievements. On 31 December 1931, he joined the Communist Party of Germany. He felt that liberals were not strong enough against the rising Nazi movement, and that communists were the only real opposition.

Koestler's Life in the 1930s

Travels and Anti-Fascist Work

Koestler wrote a book about the Soviet Five-Year Plan, but it was never fully published in Russian. Only a censored German version was released for German-speaking Soviet citizens.

In 1932, Koestler traveled in Turkmenistan and Central Asia, meeting writer Langston Hughes. In September 1933, he returned to Paris. For the next two years, he worked against Fascist movements. He wrote propaganda for Willi Münzenberg, a key communist propaganda leader.

In 1935, Koestler married Dorothy Ascher, who was also a communist activist. They separated in 1937.

Spanish Civil War and Imprisonment

In 1936, during the Spanish Civil War, Koestler visited General Francisco Franco's headquarters in Seville. He pretended to support Franco and used credentials from a London newspaper. He gathered proof that Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany were helping Franco. He had to escape after being recognized as a communist. Back in France, he wrote L'Espagne Ensanglantée, which became part of his book Spanish Testament.

In 1937, he returned to Loyalist Spain as a war reporter. He was in Málaga when it was taken by Italian troops helping Franco. Koestler was arrested and imprisoned in Seville under a death sentence. He was eventually exchanged for a high-ranking Nationalist prisoner. Koestler wrote about this experience in Dialogue with Death. His estranged wife, Dorothy, worked hard to save his life by lobbying in Britain.

Leaving the Communist Party

In July 1938, Koestler finished his novel The Gladiators. Later that year, he left the Communist Party. He then started a new novel, Darkness at Noon, published in London in 1941. He also became editor of Die Zukunft (The Future), a German weekly in Paris.

In 1939, Koestler met sculptor Daphne Hardy. They lived together in Paris. She translated Darkness at Noon from German to English. She managed to get the manuscript out of France before the German occupation and arranged for its publication in London.

World War II and Beyond

Imprisonment and Army Service

After World War II started, Koestler returned to Paris. He was arrested on 2 October 1939 and held at Stade Roland Garros. He was then moved to Le Vernet Internment Camp with other "undesirable aliens." He was released in early 1940 due to strong British pressure. Koestler wrote about this time in his memoir Scum of the Earth.

Before the German invasion of France, Koestler joined the French Foreign Legion to leave the country. He left the Legion in North Africa and tried to return to England. He heard a false report that Daphne Hardy's ship had sunk, and that she and his manuscript were lost.

When he arrived in the UK without permission, Koestler was imprisoned. While he was in prison, Daphne Hardy's English translation of Darkness at Noon was published in early 1941.

After his release, Koestler volunteered for the Army. While waiting to be called up, he wrote Scum of the Earth. For the next year, he served in the Pioneer Corps.

Propaganda Work and New Writings

In March 1942, Koestler worked for the Ministry of Information. He wrote scripts for propaganda broadcasts and films. In his free time, he wrote Arrival and Departure, another novel. He also wrote essays, collected in The Yogi and the Commissar. One essay, "On Disbelieving Atrocities," was about the Nazi crimes against Jews.

Daphne Hardy joined Koestler in London in 1943, but they separated a few months later. They remained good friends.

In December 1944, Koestler traveled to Palestine as a reporter. He secretly met Menachem Begin, the leader of the Irgun group. Koestler tried to convince him to stop militant attacks and accept a two-state solution for Palestine, but he failed.

Koestler stayed in Palestine until August 1945, gathering material for his novel Thieves in the Night. When he returned to England, Mamaine Paget was waiting for him. They moved to a cottage in Wales. Over the next three years, Koestler became good friends with writer George Orwell.

Post-War Years and Later Life

Moving to France and New Books

In 1948, when war broke out between the new State of Israel and Arab states, Koestler went to Israel as a reporter. Mamaine Paget went with him. They stayed from June to October. Later that year, they decided to move to France.

Koestler's application for British nationality was approved in December. In early 1949, he returned to London to become a British citizen.

In January 1949, Koestler and Paget moved to a house he bought in France. There, he wrote for The God That Failed and finished Promise and Fulfilment: Palestine 1917-1949. This book did not get good reviews. He also published Insight and Outlook, which also received mixed reviews. In July, Koestler started his autobiography, Arrow in the Blue. He hired Cynthia Jefferies as his secretary, who he later married.

Koestler's first wife, Dorothy, agreed to a divorce, which was finalized in December 1949. He married Mamaine Paget on 15 April 1950 in Paris.

Anti-Communist Work and Moving to the US

In June, Koestler gave a big anti-Communist speech in Berlin. He did not know that the organization sponsoring the event was secretly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the United States. In the autumn, he went to the United States for a lecture tour. He wanted to become a permanent resident there. He bought a small island with a house on the Delaware River in Pennsylvania.

In January 1951, a play based on Darkness at Noon opened in New York and won an award. Koestler gave all his earnings from the play to a fund he created to help struggling authors. In June, a bill was introduced to grant Koestler permanent residence in the U.S., and it became law in August 1951.

In 1951, Koestler's last political work, The Age of Longing, was published. It looked at Europe after the war.

In August 1952, his marriage to Mamaine ended. They separated but remained close until her sudden death in June 1954.

Settling in Britain

Koestler decided to live permanently in Britain. In May 1953, he bought a house in London and sold his houses in France and the United States.

The first two parts of his autobiography, Arrow in the Blue (covering his life until he joined the Communist Party in 1931) and The Invisible Writing (covering 1932 to 1940), were published in 1952 and 1954. A collection of essays, The Trail of the Dinosaur and Other Essays, about the dangers facing Western civilization, came out in 1955.

On 13 April 1955, Janine Graetz, with whom Koestler had a relationship, gave birth to his daughter Cristina. Koestler also campaigned to end capital punishment (hanging) in the UK.

Later Life and Awards

Koestler started working on a biography of Johannes Kepler in 1955, which was published in 1959 as The Sleepwalkers. This book became a history of how people's understanding of the universe changed, including Copernicus and Galileo.

In 1956, after the Hungarian Uprising, Koestler organized anti-Soviet meetings. In June 1957, he fell in love with a village in Austria called Alpbach. He bought land there, built a house, and used it for summer vacations and organizing meetings for twelve years.

In November 1960, he was elected to a Fellowship of The Royal Society of Literature.

In 1962, Koestler helped set up a program called Koestler Arts. This program encourages prison inmates to create art and rewards their efforts. It supports thousands of people in UK prisons each year and holds an exhibition in London.

Koestler's book The Act of Creation was published in May 1964. In November, he gave lectures at universities in California. In 1965, he married Cynthia in New York. They moved to California, where he attended seminars at Stanford University.

Koestler spent most of 1966 and early 1967 working on The Ghost in the Machine.

In April 1968, Koestler received the Sonning Prize for his "outstanding contribution to European culture." The Ghost in the Machine was published in August. He also received an honorary doctorate from a Canadian university.

In the early 1970s, Koestler published four more books: The Case of the Midwife Toad (1971), The Roots of Coincidence and The Call-Girls (both 1972), and The Heel of Achilles: Essays 1968–1973 (1974). In 1972, he was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE).

Final Years and Legacy

In 1976, Koestler was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, which made writing very difficult. He spent summers at a farmhouse in Denston, Suffolk. That same year, he published The Thirteenth Tribe, which presented his theory about the origins of Ashkenazi Jews.

In 1978, Koestler published Janus: A Summing Up. In 1980, he was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. His book Bricks to Babel was published that year. His last book, Kaleidoscope, came out in 1981.

In his final years, Koestler helped establish the KIB Society to support research "outside the scientific orthodoxies." After his death, it was renamed The Koestler Foundation.

Koestler and Cynthia died on the evening of 1 March 1983 at their London home.

His funeral was held at the Mortlake Crematorium in South London on 11 March 1983.

Koestler left most of his money, about £1 million, to support research into the paranormal. This led to the creation of a special research unit at the University of Edinburgh.

Koestler's Impact and Ideas

Writing and Influence

Koestler wrote many important novels, autobiographies, and essays. He also wrote about science, Eastern ideas, psychology, and the paranormal.

Darkness at Noon was one of the most important books ever written against the Soviet Union. It greatly influenced people in Europe, especially communists and their supporters.

Political and Social Causes

Koestler supported many different causes. These included Zionism (the movement for a Jewish homeland), communism, and later, anti-communism. He also campaigned to end capital punishment, especially hanging, and to stop the quarantine of dogs returning to the UK.

Views on Science

In his book The Case of the Midwife Toad (1971), Koestler defended biologist Paul Kammerer. Kammerer claimed to have found evidence for Lamarckian inheritance, which suggests that traits gained during an animal's life can be passed to its offspring. Koestler thought Kammerer's experiments might have been sabotaged.

Koestler criticized neo-Darwinism, a modern version of Darwin's theory of evolution. However, he was not against evolution in general. He was seen as someone who made science popular, even if his ideas were not accepted by mainstream scientists. He also believed in psychic phenomena.

Koestler was against what he called "scientific reductionism," which tries to explain everything by breaking it down into tiny parts. He gathered scientists who shared his views for meetings. While he never became a highly respected scientist, he wrote many books that explored the connection between science and philosophy.

Interest in the Paranormal

Koestler became very interested in Mysticism and the paranormal later in his life. He wrote about things like extrasensory perception (ESP), psychokinesis (moving objects with the mind), and telepathy (mind reading).

In his book The Roots of Coincidence (1972), he suggested that these phenomena cannot be explained by regular physics. He also discussed different types of coincidences, like finding information by chance. He explored the ideas of Paul Kammerer on coincidence and Carl Jung's related concepts. Koestler also studied and experimented with levitation and telepathy.

Views on Judaism

Koestler was born Jewish but did not practice the religion. In a 1950 interview, he said that Jews should either move to Israel or fully blend into the cultures where they lived.

In The Thirteenth Tribe (1976), Koestler proposed a theory that Ashkenazi Jews (most European Jews) are not descended from ancient Israelites. Instead, he suggested they came from the Khazars, a Turkic people in the Caucasus who converted to Judaism in the 8th century. Koestler believed that proving Ashkenazi Jews had no biological link to biblical Jews would help reduce anti-Semitism.

He famously said about the Balfour Declaration (which supported a Jewish homeland in Palestine): "one nation solemnly promised to a second nation the country of a third."

Working with the Information Research Department

Much of Arthur Koestler's work was secretly funded and shared by the Information Research Department (IRD). This was a hidden propaganda group of the UK Foreign Office. Koestler had strong relationships with IRD agents from 1949 and supported their goals against communism. He even advised British propagandists to create popular anti-communist books.

Languages Koestler Spoke

Koestler first learned Hungarian, but his family mostly spoke German at home. He became fluent in both languages early on. He likely also learned some Yiddish from his grandfather. By his teenage years, he was fluent in Hungarian, German, French, and English.

During his years in Palestine, Koestler became good enough at Hebrew to write stories and create the world's first Hebrew crossword puzzle. While in the Soviet Union (1932–33), he learned enough everyday Russian to speak it.

Koestler wrote his books in German until 1940. After that, he wrote only in English.

Famous Quotes

"Liking a writer and then meeting the writer is like liking goose liver and then meeting the goose."

In August 1945, Koestler was in Palestine when he read about the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. He told a friend, "That's the end of the world war, and it is also the beginning of the end of the world."

Published Works

Novels

- 1934 (2013). Die Erlebnisse des Genossen Piepvogel in der Emigration

- 1939. The Gladiators (about the revolt of Spartacus)

- 1940. Darkness at Noon

- 1943. Arrival and Departure

- 1946. Thieves in the Night

- 1951. The Age of Longing

- 1972. The Call-Girls: A Tragicomedy with a Prologue and Epilogue. A novel about scholars making a living on the international seminar-conference circuit.

Drama

- 1945. Twilight Bar.

Autobiographical Writings

- 1937. Spanish Testament.

- 1941. Scum of the Earth.

- 1942. Dialogue with Death.

- 1952. Arrow in the Blue: The First Volume of an Autobiography, 1905–31

- 1954. The Invisible Writing: The Second Volume of an Autobiography, 1932–40

- 1984. Stranger on the Square co-written with Cynthia Koestler, published after his death.

Other Non-Fiction

- 1934. Von weissen Nächten und roten Tagen. About Koestler's travels in the USSR.

- 1937. L'Espagne ensanglantée.

- 1945. The Yogi and the Commissar and Other Essays.

- 1949. Promise and Fulfilment: Palestine 1917–1949.

- 1955. The Trail of the Dinosaur and Other Essays.

- 1956. Reflections on Hanging.

- 1959. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe. An account of changing scientific ideas.

- 1960. The Watershed: A Biography of Johannes Kepler. (part of The Sleepwalkers.)

- 1960. The Lotus and the Robot. Koestler's journey to India and Japan.

- 1964. The Act of Creation.

- 1967. The Ghost in the Machine.

- 1968. Drinkers of Infinity: Essays 1955–1967.

- 1971. The Case of the Midwife Toad. About Paul Kammerer's research on Lamarckian evolution.

- 1972. The Roots of Coincidence.

- 1974. The Heel of Achilles: Essays 1968–1973.

- 1976. The Thirteenth Tribe: The Khazar Empire and Its Heritage.

- 1978. Janus: A Summing Up.

- 1980. Bricks to Babel. A collection of passages from his many books.

- 1981. Kaleidoscope. Essays and stories.

Writings as a Contributor

- Foreign Correspondent (1940) uncredited contributor to Alfred Hitchcock film

- The God That Failed (1950) (collection of stories by ex-Communists)

- Beyond Reductionism: The Alpbach Symposium. New Perspectives in the Life Sciences (co-editor with J. R. Smythies, 1969)

- The Challenge of Chance: A Mass Experiment in Telepathy and Its Unexpected Outcome (1973)

- The Concept of Creativity in Science and Art (1976)

- Life After Death, (co-editor, 1976)

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Arthur Koestler para niños

In Spanish: Arthur Koestler para niños

- Herbert A. Simon

- Holarchy

- Holism

- Holon (philosophy)

- Janus

- Politics in fiction

- Information Research Department

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |