Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific War | |

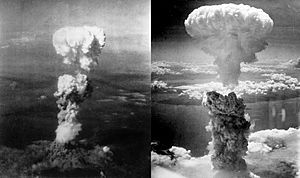

Atomic bomb mushroom clouds over Hiroshima (left) and Nagasaki (right)

|

|

| Type | Nuclear bombing |

| Location | Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan 34°23′41″N 132°27′17″E / 34.39472°N 132.45472°E 32°46′25″N 129°51′48″E / 32.77361°N 129.86333°E |

| Date | 6 and 9 August 1945 |

| Executed by |

United States

|

| Casualties |

Hiroshima:

Nagasaki:

Total killed (by end of 1945):

|

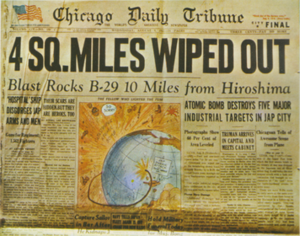

During World War II, on August 6 and 9, 1945, the United States dropped two special bombs called atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These bombings caused the deaths of about 150,000 to 246,000 people, mostly civilians. These were the only times nuclear weapons have been used in a war. Japan announced it would surrender to the Allies on August 15, just six days after the Nagasaki bombing. The war officially ended when Japan signed a surrender document on September 2, 1945.

Before these bombings, the Allies were preparing for a difficult invasion of Japan. Many Japanese cities had already been heavily bombed. American scientists in the Manhattan Project had created the atomic bombs. The Allies had asked Japan to surrender without conditions, warning of "prompt and utter destruction," but Japan did not accept. The decision to use the bombs was made to try and end the war quickly. The bombings led to much discussion about their impact and whether they were necessary.

Contents

- The Pacific War and Invasion Plans

- Preparing for the Atomic Attacks

- Hiroshima

- Events After Hiroshima

- Nagasaki

- Plans for More Attacks

- Japan Surrenders

- Reporting the Bombings

- Long-Term Health Effects

- Hibakusha (Survivors)

- Memorials and Remembrance

- Debating the Bombings

- The Legacy of Nuclear Weapons

- Related pages

- Images for kids

- See also

The Pacific War and Invasion Plans

The War in the Pacific

By 1945, the Pacific War between Japan and the Allies had been going on for four years. Japanese soldiers fought very fiercely. This meant that winning the war would be very costly for the Allies. Many American soldiers were killed or wounded, especially in the last year of the war.

As the Allies moved closer to Japan, life became very hard for the Japanese people. Their ships were destroyed, making it difficult to get raw materials. This caused Japan's economy to suffer greatly. Food became scarce, and many people faced hunger. By February 1945, some Japanese leaders knew that defeat was unavoidable.

Planning to Invade Japan

Even before Germany surrendered in May 1945, the Allies were planning a huge invasion of Japan. This plan was called Operation Downfall. It involved two main parts: first, capturing the southern part of Japan's island of Kyushu in October 1945. Then, capturing the area near Tokyo on the island of Honshu in March 1946.

Japan's leaders knew where the Allies would likely attack. They prepared a strong defense, planning for almost all their forces to fight on Kyushu. They had 2.3 million soldiers ready to defend Japan. They also had a civilian militia of 28 million people. Everyone expected many deaths on both sides if an invasion happened.

Air Attacks on Japan

The United States began bombing Japan in mid-1944 using Boeing B-29 Superfortress planes. At first, they tried to bomb specific factories from high altitudes. However, this was difficult due to long distances, plane problems, and bad weather.

Later, in January 1945, Major General Curtis LeMay changed tactics. He decided to use low-flying planes to drop incendiary bombs on Japanese cities. These bombs were designed to start huge fires. The goal was to destroy Japan's ability to make war supplies and lower the morale of its people.

Over the next six months, American planes firebombed 64 Japanese cities. The firebombing of Tokyo on March 9–10, 1945, was especially destructive. It killed about 100,000 people and destroyed a large part of the city. By mid-June, Japan's six biggest cities were devastated. Japanese defenses struggled to stop these attacks.

Developing the Atomic Bomb

Scientists discovered nuclear fission in 1938, which made the idea of an atomic bomb possible. Fearing that Germany might build such a weapon first, the United States started its own research. This effort grew into the Manhattan Project, a top-secret project led by Major General Leslie R. Groves, Jr..

The Manhattan Project involved many sites across the U.S. and cost billions of dollars. J. Robert Oppenheimer led the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico, where the bombs were designed. Two types of bombs were created: "Little Boy" (using uranium-235) and "Fat Man" (using plutonium-239). Japan also had a nuclear weapon program, but it did not make much progress.

Preparing for the Atomic Attacks

Training and Organization

The 509th Composite Group was formed in December 1944, led by Colonel Paul Tibbets. Their job was to learn how to deliver an atomic weapon. They trained at Wendover Army Air Field in Utah, practicing bomb drops. Some missions over Japan were flown by single bombers to get the Japanese used to this pattern.

The 509th Group used 15 special B-29 planes called Silverplate B-29s. These planes were changed to carry the atomic bombs and had many improvements. The group's ground crew and equipment were sent to Tinian, an island in the Pacific.

Choosing the Targets

In April 1945, a special committee chose targets for the atomic bombs. The main targets were Kokura, Hiroshima, Yokohama, Niigata, and Kyoto. These cities were chosen because they were large urban areas with military importance. They had also been mostly untouched by previous air raids, which would allow for a clear assessment of the atomic bomb's damage.

Hiroshima was described as an important military and industrial center. It was also noted that nearby hills might increase the bomb's blast damage. The committee also considered the psychological impact of the bombing. They wanted the first use to be spectacular enough for the world to understand the weapon's importance.

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson asked to remove Kyoto from the list because of its historical and cultural importance. President Harry S. Truman agreed. Nagasaki was then added to the target list instead of Kyoto. Nagasaki was a major military port and a center for shipbuilding.

Discussing a Demonstration

A group called the Interim Committee decided that the atomic bomb should be used against Japan as soon as possible. They also decided it should be used without a special warning and on a target that included both military facilities and other buildings.

Some scientists suggested showing the Japanese a non-combat demonstration of the bomb. However, others worried that a demonstration might not convince Japan to surrender. They also feared that if the demonstration failed, it would make the Allies look weak. They believed that the shock of a surprise attack would be more effective in ending the war.

Warnings to Civilians

For several months, the U.S. had dropped millions of leaflets over Japan. These leaflets warned civilians about potential air raids. Many Japanese cities had already been severely damaged by conventional bombings. The leaflets encouraged people to leave major cities.

However, no special warning was given to Hiroshima that a new, much more powerful bomb would be dropped. The decision was made to maximize the shock effect on Japan's leaders.

The Potsdam Declaration

After a successful test of the atomic bomb on July 16, 1945, Allied leaders issued the Potsdam Declaration on July 26. This document told Japan the terms for its surrender. It warned that if Japan did not surrender, it would face "prompt and utter destruction." The atomic bomb was not directly mentioned.

On July 28, Japan's Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki announced that the government would ignore the ultimatum. Emperor Hirohito did not try to change this decision. Japan was only willing to surrender if certain conditions were met, such as keeping the Emperor in power.

The Bombs Arrive

The "Little Boy" bomb, without its uranium, was ready by early May 1945. Its parts were completed in June and July. The main parts of the bomb were shipped to Tinian island on July 16 aboard the cruiser USS Indianapolis. Other parts arrived by air on July 30. The bomb was designed so it could be armed while the plane was flying, to make takeoff safer.

The first plutonium core for the "Fat Man" bomb arrived at Tinian on July 28. Three "Fat Man" bomb parts were also flown to Tinian, arriving on August 2.

Hiroshima

Hiroshima During the War

Hiroshima was an important city for Japan's military and industry. It was home to the headquarters of the Second General Army, which defended southern Japan. About 40,000 Japanese military personnel were stationed there.

The city was a key center for supplies, shipping, and troop assembly. It also had many factories that made parts for planes, boats, bombs, and guns. Most buildings were made of wood, making the city very vulnerable to fire. Hiroshima had been largely spared from earlier air raids. Its population was about 340,000–350,000 at the time of the attack.

The Bombing of Hiroshima

Hiroshima was the main target for the first atomic bombing mission on August 6. The B-29 plane Enola Gay, piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets, took off from Tinian island early that morning. Two other B-29s, The Great Artiste and Necessary Evil, flew with it for instrumentation and photography.

The planes flew towards Japan. To reduce risks during takeoff, the bomb was armed while the Enola Gay was in flight. About an hour before the bombing, an air raid alert sounded in Hiroshima, but it was cleared shortly after.

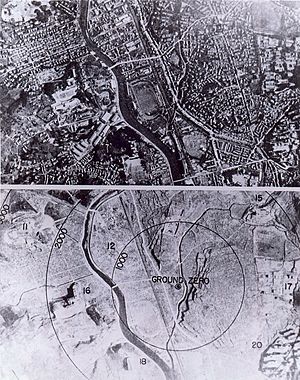

At 8:15 AM (Hiroshima time), the "Little Boy" bomb was released. It fell for 44 seconds before exploding about 1,900 feet above the city. The bomb missed its exact target but detonated over the Shima Surgical Clinic. It released energy equal to about 16,000 tons of TNT. The explosion destroyed everything within about one mile, and fires spread across 4.4 square miles.

The crew of the Enola Gay saw a tremendous and awe-inspiring sight. Only Tibbets and two others knew the true nature of the weapon. The crew received a hero's welcome when they landed back on Tinian.

What Happened on the Ground

People on the ground saw a brilliant flash of light, followed by a loud boom. Survivors often described feeling like a huge conventional bomb had exploded right next to them. They soon realized that the entire city had been hit at once. Many people were trapped in collapsed buildings or suffered horrific burns. As small fires grew, they merged into a huge firestorm that swept through the city.

Estimating the exact number of deaths has been difficult. Reports from the 1970s suggest about 140,000 people died in Hiroshima by the end of 1945. Modern estimates suggest between 90,000 and 166,000 people died by the end of that year. About 90% of those who died were civilians.

U.S. surveys estimated that 4.7 square miles of the city were destroyed. Japanese officials said 69% of buildings were destroyed. Some strong concrete buildings survived, like the Prefectural Industrial Promotional Hall, now known as the Genbaku (A-bomb) dome. It was only about 150 meters from where the bomb exploded. This ruin became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996.

Over 90% of doctors and nurses in Hiroshima were killed or injured. Hospitals were destroyed. Field Marshal Shunroku Hata, who was only slightly wounded, helped organize relief efforts. Soldiers used boats to rescue the wounded from the rivers.

Twelve American airmen were imprisoned in Hiroshima. Most died instantly in the blast. Some were reported to have been executed later. After the explosion, a "black rain" fell, which was a mix of ash, radioactive fallout, and water. This caused severe radiation burns in some cases.

Japan Learns of the Bombing

The Tokyo control center for Japan's broadcasting company noticed that the Hiroshima station went off the air. Railroad telegraph lines near Hiroshima also stopped working. Unofficial reports of a terrible explosion came from small railway stops. These reports reached the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff.

Military leaders were puzzled because no large enemy raid was expected. A young officer was sent to fly to Hiroshima to see the damage. He and his pilot saw a huge cloud of smoke from about 160 kilometers away. After circling the city, they landed and reported to Tokyo that the city had been destroyed by a new type of bomb. Tokyo officially learned of the attack from President Truman's announcement sixteen hours later.

Events After Hiroshima

After the Hiroshima bombing, President Truman announced the use of the new weapon. He warned Japan that if they did not surrender, they could expect "a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth." This message was broadcast widely to Japan.

On August 9, at two minutes past midnight, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria. This added more pressure on Japan to surrender.

On August 7, Japanese atomic physicists examined Hiroshima and confirmed it was destroyed by a nuclear weapon. Despite this, some military leaders decided to continue fighting. American codebreakers intercepted messages showing the Japanese cabinet's discussions.

American military leaders met on Guam and decided to drop another bomb since Japan had not surrendered. They aimed to have it ready by August 9, earlier than planned, due to bad weather forecasts.

Nagasaki

Nagasaki During the War

Nagasaki was a large seaport in southern Japan and very important for wartime industry. It had major companies like Mitsubishi that produced ships, military equipment, and other war materials. Even though it was an important industrial city, Nagasaki had not been heavily firebombed because its hilly geography made it hard to target at night.

Most buildings in Nagasaki were old-fashioned Japanese style, made of wood. Many factories and homes were built very close together. On the day of the bombing, about 263,000 people were in Nagasaki, including Japanese residents, Korean workers, and soldiers.

The Bombing of Nagasaki

The second bombing mission, scheduled for August 11, was moved up to August 9 to avoid bad weather. The B-29 plane Bockscar, flown by Major Charles Sweeney's crew, took off from Tinian with the "Fat Man" bomb. Kokura was the primary target, and Nagasaki was the secondary target.

During the flight, the crew faced several problems, including a faulty fuel pump. When they reached Kokura, the city was covered by clouds and smoke from earlier bombings in a nearby city. After three attempts to drop the bomb visually, the bombardier could not see the target. With fuel running low, Bockscar headed for Nagasaki.

At 11:01 AM (Japanese time), a break in the clouds over Nagasaki allowed the bombardier to see the target. The "Fat Man" bomb, containing plutonium, was dropped over the city's industrial valley. It exploded 47 seconds later at 11:02 AM, about 1,650 feet above a tennis court. The blast was mostly contained by the surrounding hills, protecting a large part of the city. The explosion released energy equal to about 21,000 tons of TNT.

Bockscar then flew to Okinawa, landing with very little fuel left. Unlike the welcome for the Enola Gay, no one was there to greet them, as no one knew they were coming.

What Happened on the Ground in Nagasaki

Even though the Nagasaki bomb was more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb, its effects were limited by the hills to the narrow Urakami Valley. Many workers in the Mitsubishi Munitions plant were killed. Estimates suggest about 70,000 people died in Nagasaki by the end of 1945. A modern estimate suggests between 60,000 and 80,000 people died by the end of that year.

Only about 150 Japanese soldiers were killed instantly. At least eight Allied prisoners of war also died. The Nagasaki Arsenal was destroyed. Many fires burned after the bombing, but a large firestorm like in Hiroshima did not develop.

The bombing severely damaged Nagasaki's medical facilities. A temporary hospital was set up in a primary school. Medical teams from nearby towns helped treat victims. About 20 minutes after the bombing, a black rain fell, carrying radioactive material.

Plans for More Attacks

The U.S. had plans for more atomic attacks on Japan. Another "Fat Man" bomb was expected to be ready by August 19, with more in September and October. However, President Truman decided to stop the atomic bombings. He said that the thought of killing another 100,000 people was too terrible. He ordered that no more atomic bombs would be used without his direct permission.

Japan Surrenders

Until August 9, Japan's war council still insisted on four conditions for surrender. The full cabinet debated surrender for most of that day but could not agree. Prime Minister Kantarō Suzuki then met with Emperor Hirohito, who agreed to hold an imperial conference. The Emperor indicated he would accept surrender if his position as ruler could be preserved.

On August 10, the Emperor made his "sacred decision," agreeing to surrender on the condition that his role as sovereign ruler was not harmed. On August 14, Emperor Hirohito recorded his surrender announcement, which was broadcast to the Japanese nation the next day. This happened despite an attempted military coup by those who opposed surrender.

In his announcement, Emperor Hirohito mentioned the "new and most cruel bomb" that caused "incalculable" damage and took "many innocent lives." He stated that continuing to fight would lead to the "total extinction of human civilization."

Three weeks after the bombings, Colonel Tibbets visited Nagasaki and was amazed by the destruction caused by just one bomb. He described it as "eerie" and "scares the hell out of you."

Reporting the Bombings

On August 10, 1945, a military photographer named Yōsuke Yamahata arrived in Nagasaki to document the destruction. His photos were later published in a Japanese newspaper. After Japan surrendered, American forces censored many of these images.

Early reports from journalists like Leslie Nakashima and Wilfred Burchett informed the public about the terrible effects of radiation and nuclear fallout. They described people dying from radiation sickness, with symptoms like bleeding and rotting flesh. These reports shocked many.

However, some U.S. officials tried to downplay the effects of radiation sickness, calling them Japanese propaganda. General MacArthur, who led the occupation of Japan, even threatened to punish journalists who reported on the gruesome scenes.

A U.S. film crew documented the effects of the bombings in early 1946, creating a three-hour documentary. This film was kept secret for 22 years. Japanese film crews also recorded the aftermath, but their footage was confiscated by American authorities before being declassified later.

The book Hiroshima by John Hersey, published in 1946, told the stories of six survivors. It helped people understand the human impact of the bombings. Later, a collection of drawings by survivors, called The Unforgettable Fire, was also created.

Long-Term Health Effects

Many people who survived the initial blasts and fires later died from health problems caused by radiation exposure. Doctors at the time did not understand what was happening and could not effectively treat the condition, which became known as "atomic bomb disease."

In 1948, the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) was set up to study the long-term effects of radiation on survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This organization later became the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF) in 1975 and continues its work today.

Cancer Risks

Cancers caused by radiation usually take several years to appear. For example, leukemia often appears two years or more after exposure. Studies have shown an increased risk of certain cancers, like leukemia and solid cancers, among survivors who were exposed to significant amounts of radiation. However, the average lifespan of survivors was reduced by only a few months compared to those not exposed to radiation.

Birth Defects

Early studies by the ABCC looked at the health of babies born to pregnant women who were exposed to the bombings. Overall, the number of birth defects was not significantly higher among these children. However, in a small group of babies whose mothers were very close to the explosion and were in the early stages of pregnancy, there was an increase in certain brain conditions like microencephaly (small head size).

Later research confirmed that there was no statistically significant increase in birth defects among the children of survivors. Even decades later, studies found no evidence that birth defects were common or inherited in the children of survivors.

Hibakusha (Survivors)

The survivors of the atomic bombings are called hibakusha (被爆者, or), which means "explosion-affected people." The Japanese government has recognized about 650,000 people as hibakusha. As of March 31, 2025, about 99,130 were still alive, mostly in Japan.

Sadly, hibakusha and their children often faced discrimination in marriage or work. Many people wrongly believed that they carried a contagious disease or had inherited health problems. This was despite studies showing no significant increase in birth defects in the children of survivors.

Double Survivors

Some people who survived the Hiroshima bombing later went to Nagasaki and survived that bombing too. These individuals are called nijū hibakusha (double explosion-affected people). In 2009, Tsutomu Yamaguchi was officially recognized as the first double hibakusha. He was about 3 kilometers from the blast in Hiroshima and then exposed to radiation in Nagasaki the next day. He died in 2010 from stomach cancer.

Korean Survivors

During the war, many Koreans were brought to Japan for forced labor. About 5,000–8,000 Koreans were killed in Hiroshima and 1,500–2,000 in Nagasaki. Many Korean survivors faced difficulties getting the same recognition and health benefits as Japanese survivors. These issues were largely addressed through lawsuits by 2008.

Memorials and Remembrance

Hiroshima Memorials

After the war, Hiroshima was rebuilt with help from the Japanese government. In 1949, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park was designed. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial, also known as the Genbaku Dome, is the closest surviving building to where the bomb exploded. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum opened in 1955 in the Peace Park.

Many commemorative plaques have been placed at historical sites related to the bombing, including the Shima Hospital (hypocenter) and the Motoyasu Bridge.

Nagasaki Memorials

Nagasaki was also rebuilt and changed significantly after the war. The city focused on foreign trade, shipbuilding, and fishing. The Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum opened in the mid-1990s.

Some rubble was kept as memorials, such as a torii gate at Sannō Shrine and an arch near ground zero. In 2016, several sites, including the former Nagasaki City Shiroyama Elementary School and the former Urakami Cathedral Belfry, were designated as National Historic Sites.

Debating the Bombings

There is still much debate about whether the atomic bombings were necessary and right.

Some argue that the bombings forced Japan to surrender, which prevented a costly invasion. They believe this saved many lives, both Allied and Japanese, that would have been lost in an invasion.

Others argue that the bombings were not needed to end the war. They believe Japan might have surrendered anyway, perhaps due to the Soviet Union joining the war. Some also argue that using atomic weapons was a terrible act. Another view is that the U.S. used the bombs to show its power to the Soviet Union at the start of the Cold War.

The Legacy of Nuclear Weapons

After Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the United States continued to develop more atomic bombs. In 1949, the Soviet Union also developed its own atomic bomb, starting a nuclear arms race. The U.S. then developed the hydrogen bomb, which was much more powerful.

By 2020, nine nations had nuclear weapons. Japan, which does not have nuclear weapons, is protected by the United States under a "nuclear umbrella." This means the U.S. would use its nuclear weapons to defend Japan if needed.

On July 7, 2017, over 120 countries voted to adopt the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. This treaty aims to ban nuclear weapons worldwide. As of 2024, Japan has not signed this treaty.

Related pages

Images for kids

-

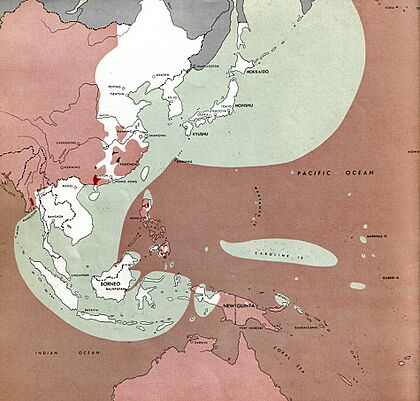

Leslie Groves, Manhattan Project director, with a map of Japan

-

Aircraft of the 509th Composite Group that took part in the Hiroshima bombing. Left to right: Big Stink, The Great Artiste, Enola Gay

-

The Enola Gay dropped the "Little Boy" atomic bomb on Hiroshima. Paul Tibbets (center in photograph) can be seen with six of the aircraft's crew.

-

For decades this "Hiroshima strike" photo was misidentified as the mushroom cloud of the bomb that formed at c. 08:16. However, due to its much greater height, the scene was identified by a researcher in March 2016 as the firestorm-cloud that engulfed the city, a fire that reached its peak intensity some three hours after the bomb.

-

The Bockscar and its crew, who dropped a Fat Man atomic bomb on Nagasaki

-

A telegram sent by Fritz Bilfinger, delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), on 30 August 1945 from Hiroshima

-

Torii, Nagasaki, Japan. One-legged torii in the background

-

Memorial at Andersonville NHS for the American airmen who died in the blast.

See also

In Spanish: Bombardeos atómicos de Hiroshima y Nagasaki para niños

In Spanish: Bombardeos atómicos de Hiroshima y Nagasaki para niños