Manhattan Project facts for kids

The Manhattan Project was a top-secret program in the United States. Its goal was to build the world's first nuclear weapons. This huge project took place during World War II. The U.S. Army was in charge of it.

General Leslie R. Groves led the project. He had also overseen the building of the Pentagon. The main scientist was Robert Oppenheimer, a very smart physicist. The project cost about $2 billion. It created many secret cities and factories. These included a lab in Los Alamos, New Mexico, a nuclear reactor in Hanford, Washington, and a uranium processing plant in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The Manhattan Project faced two big challenges. The first was how to make special materials. These materials are called isotopes, like uranium-235 or plutonium. They are needed to create a nuclear explosion. This process, called separation, was very slow. The United States built huge buildings with different machines to do this. They made enough of these special materials for a few nuclear weapons.

The second challenge was designing a bomb that would explode with a huge nuclear blast every time. A poorly designed weapon might only make a small explosion, called a "fizzle." In July 1945, the project solved both problems. They successfully tested the first nuclear explosion. This test was named "Trinity."

The Manhattan Project created two nuclear bombs. The United States used these bombs against Japan in 1945.

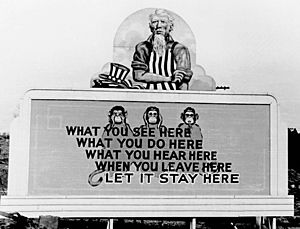

Keeping the Project a Secret

The Manhattan Project was kept very secret. This was to stop the Axis countries, especially Nazi Germany, from speeding up their own nuclear plans. It also prevented them from trying to harm the project. There was always a worry about sabotage. Sometimes, when equipment broke down, people thought it might be sabotage.

While some problems were due to careless workers, there were no confirmed cases of enemy sabotage. However, on March 10, 1945, a Japanese fire balloon hit a power line. This caused a power surge that temporarily shut down three reactors at Hanford.

Keeping the project secret was hard because so many people worked on it. A special group from the Counter Intelligence Corps handled security. By 1943, it was clear that the Soviet Union was trying to get information about the project. Lieutenant Colonel Boris T. Pash investigated suspected Soviet spying. Oppenheimer himself told Pash that another professor had asked him to pass information to the Soviet Union.

The most successful Soviet spy was Klaus Fuchs. He was a British scientist who worked at Los Alamos. When Fuchs' spying was discovered in 1950, it hurt the nuclear cooperation between the United States, Britain, and Canada. Later, other spies were found, leading to arrests like Harry Gold and Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. Some spies, like George Koval, remained unknown for many years.

It's hard to know exactly how much the spying helped the Soviets. One reason is that the Soviet atomic bomb project had trouble getting enough uranium. Most experts agree that the spying saved the Soviets one or two years of work.

Images for kids

-

Enrico Fermi, John R. Dunning, and Dana P. Mitchell in front of the cyclotron in the basement of Pupin Hall at Columbia University

-

March 1940 meeting at Berkeley, California: Ernest O. Lawrence, Arthur H. Compton, Vannevar Bush, James B. Conant, Karl T. Compton, and Alfred L. Loomis

-

Oppenheimer and Groves at the remains of the Trinity test in September 1945, two months after the test blast and just after the end of World War II. The white overshoes prevented fallout from sticking to the soles of their shoes.

-

Groves confers with James Chadwick, the head of the British Mission.

-

Shift change at the Y-12 uranium enrichment facility at the Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, on 11 August 1945. By May 1945, 82,000 people were employed at the Clinton Engineer Works. Photograph by the Manhattan District photographer Ed Westcott.

-

Physicists at a Manhattan District-sponsored colloquium at the Los Alamos Laboratory on the Super in April 1946. In the front row are Norris Bradbury, John Manley, Enrico Fermi and J. (Jerome) M. B. Kellogg. Robert Oppenheimer, in dark coat, is behind Manley; to Oppenheimer's left is Richard Feynman. The Army officer on the left is Colonel Oliver Haywood.

-

The majority of the uranium used in the Manhattan Project came from the Shinkolobwe mine in Belgian Congo.

-

Aerial view of Hanford B-Reactor site, June 1944

-

The Trinity test of the Manhattan Project was the first detonation of a nuclear weapon.

-

Allied soldiers dismantle the German experimental nuclear reactor at Haigerloch.

-

Presentation of the Army–Navy "E" Award at Los Alamos on 16 October 1945. Standing, left to right: J. Robert Oppenheimer, unidentified, unidentified, Kenneth Nichols, Leslie Groves, Robert Gordon Sproul, William Sterling Parsons.

-

President Harry S. Truman signs the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, establishing the United States Atomic Energy Commission.

-

The Lake Ontario Ordnance Works (LOOW) near Niagara Falls became a principal repository for Manhattan Project waste for the Eastern United States. All of the radioactive materials stored at the LOOW site—including thorium, uranium, and the world's largest concentration of radium-226—were buried in an "Interim Waste Containment Structure" (in the foreground) in 1991.

-

After the reaction, the interior of a bomb coated with remnant slag

-

A uranium metal "biscuit" from the reduction reaction

See also

In Spanish: Proyecto Manhattan para niños

In Spanish: Proyecto Manhattan para niños