Enrico Fermi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Enrico Fermi

|

|

|---|---|

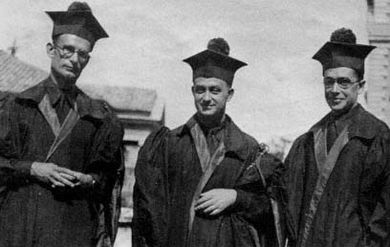

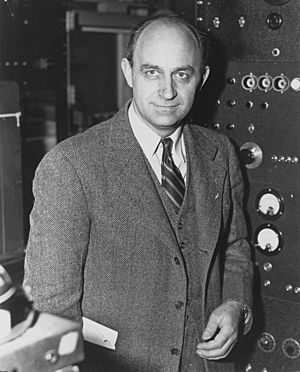

Fermi in 1943

|

|

| Born | 29 September 1901 Rome, Italy

|

| Died | 28 November 1954 (aged 53) Chicago, Illinois, US

|

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, Italy (laurea) |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) | Laura Capon Fermi |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions |

|

| Academic advisors |

|

| Doctoral students |

|

| Other notable students | |

| Signature | |

|

|

Enrico Fermi (born September 29, 1901 – died November 28, 1954) was a brilliant Italian physicist. He later became an American citizen. He is famous for creating the world's first nuclear reactor, called the Chicago Pile-1. People often call him the "architect of the nuclear age" and the "architect of the atomic bomb."

Fermi was one of the few scientists who was excellent at both theoretical physics (thinking about how things work) and experimental physics (doing hands-on tests). In 1938, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics. This was for his work on making materials radioactive by shooting tiny particles called neutrons at them. He also thought he had found new, heavier elements, though this was later corrected.

Fermi and his team created many inventions related to nuclear power. The US government later took over these inventions. He made big discoveries in how tiny particles behave, how energy works in atoms, and how particles interact.

Fermi's first major work was in understanding how many particles behave together. After another scientist, Wolfgang Pauli, described his "exclusion principle" in 1925, Fermi used it to explain how particles in a gas behave. This idea is now called Fermi–Dirac statistics. Particles that follow this rule are called "fermions."

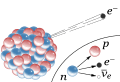

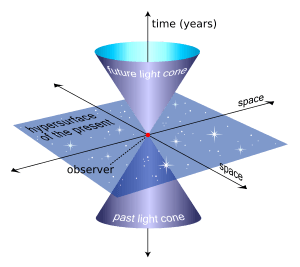

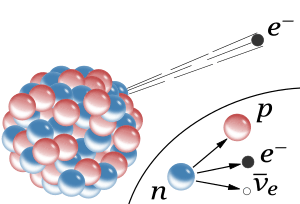

Later, Pauli suggested there was a tiny, invisible particle released during a process called beta decay. This particle had no charge and very little mass. Fermi took this idea and developed a model for it, naming the particle the "neutrino." His theory, now called the weak interaction, describes one of the four basic forces in nature.

Through experiments, Fermi found that slow-moving neutrons were much better at being captured by atomic nuclei than fast ones. He developed an equation to explain this. He thought he had created new elements by hitting thorium and uranium with slow neutrons. Even though he won the Nobel Prize for this, it was later discovered that these were actually pieces from the atom splitting apart.

In 1938, Fermi left Italy because of new Italian racial laws that affected his Jewish wife, Laura Capon. He moved to the United States. There, he worked on the Manhattan Project during World War II.

Fermi led the team at the University of Chicago that built Chicago Pile-1. This reactor started working on December 2, 1942. It was the first time humans had created a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction. He also helped with other important reactors. At Los Alamos, he led a division that worked on the thermonuclear "Super" bomb. He was at the Trinity test in 1945. There, he used his quick estimation method, the Fermi method, to guess the bomb's power.

After the war, Fermi advised the United States Atomic Energy Commission on nuclear matters. He was against developing the hydrogen bomb because of moral and technical reasons. He also supported J. Robert Oppenheimer during a hearing in 1954. Fermi did important work on tiny particles like pions and muons. He also thought that cosmic rays came from material sped up by magnetic fields in space.

Many awards, ideas, and places are named after Fermi. These include the Enrico Fermi Award, the Enrico Fermi Institute, the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, and the element fermium. He is one of only 16 scientists to have an element named after them. Fermi taught or influenced at least eight young scientists who later won Nobel Prizes.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Enrico Fermi was born in Rome, Italy, on September 29, 1901. He was the third child of Alberto Fermi, who worked for the railways, and Ida de Gattis, a school teacher. He had an older sister, Maria, and an older brother, Giulio. Enrico loved building electric motors and playing with mechanical toys with Giulio. Sadly, Giulio died during an operation in 1915.

When he was young, Fermi found an old physics book written in Latin. He and his friend, Enrico Persico, used it to build things like gyroscopes. They also measured the pull of Earth's gravity.

In 1914, Fermi met Adolfo Amidei, a colleague of his father. Adolfo was impressed by young Fermi's interest in math and physics. He gave Fermi books on these subjects. Fermi would read them quickly and remember everything. Adolfo realized Fermi was a "prodigy" in geometry.

Studying in Pisa

Fermi finished high school early in July 1918. Amidei encouraged him to learn German to read scientific papers. Fermi then applied to the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa in Pisa. He got the top score on the entrance exam. For the essay, he used advanced math to solve a problem about sound. The examiner knew right away that Fermi would be an amazing physicist.

At the school, Fermi became close friends with Franco Rasetti. They often played pranks together. Fermi's professor, Luigi Puccianti, said he had little to teach Fermi. Instead, he often asked Fermi to teach him! Fermi knew so much about quantum physics that he led seminars on it. He also learned tensor calculus, which is important for general relativity.

Fermi first chose math as his main subject but soon switched to physics. He mostly taught himself by reading about general relativity, quantum mechanics, and atomic physics. In 1920, he was accepted into the Physics department. Since there were only three students, Fermi, Rasetti, and Nello Carrara, they could use the lab freely. They decided to study X-ray crystallography.

Fermi published his first scientific papers in 1921. One paper showed how mass changes with speed in relativity. Another used general relativity to show that energy has weight. In 1922, he wrote about world lines and introduced "Fermi coordinates." He showed that space acts like a flat, normal space near a timeline.

Fermi finished his degree in July 1922, at the young age of 20. His thesis was about X-ray diffraction. At that time, theoretical physics was not a separate field in Italy. So, Fermi had to do experimental work for his thesis.

In 1923, Fermi was the first to point out that Einstein's famous equation (E=mc²) contained a huge amount of nuclear energy. He wrote that it seemed impossible to release this energy soon. He joked that if someone did, the first effect would be to blow up the physicist!

Fermi studied with famous physicists like Max Born in Germany and Paul Ehrenfest in the Netherlands. He met Werner Heisenberg, Albert Einstein, and Hendrik Lorentz. From 1925 to 1926, Fermi taught physics at the University of Florence. He worked with Rasetti on experiments with mercury vapor. He also gave talks on quantum mechanics.

In 1925, after Wolfgang Pauli announced his exclusion principle, Fermi applied it to a gas. This led to his statistical method, now called Fermi–Dirac statistics. Particles that follow this rule are called "fermions."

Professor in Rome

In 1926, at age 24, Fermi became a professor at the Sapienza University of Rome. This was a new position for theoretical physics in Italy. Professor Orso Mario Corbino helped Fermi build his team. This group included talented students like Edoardo Amaldi, Bruno Pontecorvo, Ettore Majorana, and Emilio Segrè. Franco Rasetti also joined as his assistant. They became known as the "Via Panisperna boys" after the street where their lab was.

Fermi married Laura Capon in 1928. They had two children, Nella and Giulio. In 1929, Fermi became a member of the Royal Academy of Italy. He later opposed Fascism when new racial laws were introduced in 1938. These laws affected his Jewish wife and many of his assistants.

In Rome, Fermi and his team made big discoveries. In 1928, he published a book called Introduction to Atomic Physics. It helped Italian students learn about new physics ideas. Fermi also gave public talks and wrote articles to share this knowledge. He often gathered his students to solve problems from his own research.

Discovering the Neutrino

At this time, scientists were confused by beta decay, where an electron is shot out of an atomic nucleus. To make sure energy was conserved, Pauli suggested there was an invisible particle with no charge. Fermi developed this idea in 1933 and called the particle a "neutrino." His theory, known as the weak interaction, describes one of the four basic forces of nature.

When Fermi sent his paper to a British science journal, the editor rejected it. They thought his ideas were "too remote from physical reality." So, Fermi's theory was first published in Italian and German. The neutrino was finally detected after his death.

Neutron Experiments

In 1934, scientists Irène Joliot-Curie and Frédéric Joliot found they could make elements radioactive by hitting them with alpha particles. Fermi decided to try using neutrons, which James Chadwick had discovered in 1932. Neutrons have no electric charge, so they could easily enter an atom's nucleus. This meant Fermi didn't need a powerful particle accelerator.

Fermi used a strong neutron source made from radon and beryllium. He started by hitting platinum with neutrons, but nothing happened. Then he tried aluminium, which became radioactive and changed into sodium. He made 22 different elements radioactive. Fermi quickly reported his discovery in an Italian journal in March 1934.

It was hard to study thorium and uranium because they were already naturally radioactive. But Fermi thought he had created new elements, which he called hesperium and ausonium. He even won the Nobel Prize for this discovery. However, a chemist named Ida Noddack suggested that the uranium might have split into lighter elements. At the time, scientists thought splitting an atom was impossible.

The Via Panisperna boys also noticed something strange. Their experiments worked better on a wooden table than a marble one. Fermi remembered that paraffin wax could slow down neutrons. He tried it, and it made silver a hundred times more radioactive! He realized that hydrogen atoms in the paraffin (and wood) slowed the neutrons. Slower neutrons were much easier for atoms to capture. He developed an equation to explain this, called the Fermi age equation.

In 1938, Fermi received the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work. After getting the prize in Sweden, he did not return to Italy. Instead, he and his family moved to New York City in December 1938. They wanted to become US citizens because of the racial laws in Italy.

The Manhattan Project

Fermi arrived in New York City on January 2, 1939. He was offered jobs at five universities and chose Columbia University. Soon after, he heard big news: German chemists had found barium after hitting uranium with neutrons. Other scientists, Lise Meitner and Otto Frisch, realized this meant the uranium atom had split in half. This process was called nuclear fission.

This news was a big surprise for Fermi. He had dismissed the idea of fission based on his calculations. It meant that the "new elements" he had won the Nobel Prize for were actually just pieces of split uranium atoms. He added a note about this to his Nobel Prize speech.

Scientists at Columbia decided to try to detect the energy released by fission. On January 25, 1939, Fermi and his team did the first nuclear fission experiment in the United States. French scientists then showed that uranium, when hit by neutrons, released even more neutrons. This suggested a chain reaction was possible. Fermi and another scientist, Leó Szilárd, worked together to design a device for a self-sustaining nuclear reaction – a nuclear reactor.

Fermi suggested using uranium oxide blocks and graphite instead of water to slow down neutrons. This would make a chain reaction possible. Szilárd designed a working model: a pile of uranium oxide blocks mixed with graphite bricks.

Fermi was one of the first to warn military leaders about the power of nuclear energy. In 1939, Szilárd, Eugene Wigner, and Edward Teller sent a letter signed by Albert Einstein to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It warned that Nazi Germany might build an atomic bomb. Roosevelt then formed a committee to investigate.

The committee gave Fermi money to buy graphite. He built bigger and bigger piles of graphite and uranium oxide at Columbia University. In 1941, the US entered World War II, making this work very urgent. The committee decided to focus on making plutonium at the University of Chicago. Fermi moved there, and his team became part of the new Metallurgical Laboratory.

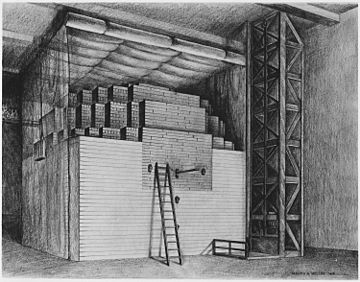

Building the first nuclear reactor in the middle of Chicago seemed risky. So, a location in the Argonne Woods Forest Preserve was chosen. But construction stopped due to a worker dispute. Fermi then convinced everyone that he could build the reactor safely in a squash court under the stands of the University of Chicago's Stagg Field. Construction of the "pile" began on November 6, 1942. On December 2, Chicago Pile-1 started working, creating the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction.

This experiment was a huge step in the search for energy. Fermi planned every step and calculation very carefully. After the chain reaction was achieved, a coded phone call was made to announce the success.

To continue research safely, the reactor was taken apart and moved to the Argonne Woods site. Fermi led experiments there, using the reactor's many free neutrons. The lab soon expanded into biological and medical research. Fermi became an American citizen in July 1944.

In September 1944, Fermi helped start the B Reactor at the Hanford Site. This was a much larger reactor designed to produce large amounts of plutonium. It went critical, meaning it started a chain reaction. But then, the power level dropped, and the reactor shut down. Fermi and John Wheeler figured out the problem. A fission product called xenon-135 was absorbing the neutrons, stopping the reaction. Fermi realized that if all the reactor's tubes were loaded with fuel, it could reach the needed power level.

In mid-1944, J. Robert Oppenheimer convinced Fermi to join Project Y at Los Alamos, New Mexico. Fermi became an associate director, in charge of nuclear and theoretical physics. He observed the Trinity test on July 16, 1945. He used his "Fermi method" to quickly estimate the bomb's power by dropping paper strips into the blast wave. His estimate was very close to the actual power.

Fermi, Oppenheimer, and other scientists advised on where to drop the atomic bombs. They agreed the bombs should be used without warning on an industrial target. Fermi learned about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from a public announcement. He didn't believe atomic bombs would stop wars, nor did he think a world government was ready.

Postwar Work and Legacy

Fermi became a professor at the University of Chicago in July 1945. He was elected to the US National Academy of Sciences. The Metallurgical Laboratory became the Argonne National Laboratory in 1946. Fermi worked at both places. At Argonne, he continued experiments on neutron scattering. He also helped Maria Goeppert Mayer with her work, which later won her a Nobel Prize.

Fermi served on the United States Atomic Energy Commission's General Advisory Committee. He also spent time at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. There, he worked with Nicholas Metropolis and John von Neumann on how fluids mix.

After the Soviet Union tested its first fission bomb in 1949, Fermi and Isidor Rabi wrote a strong report against developing a hydrogen bomb. They had moral and technical reasons. However, Fermi continued to advise on the hydrogen bomb project. He also supported Oppenheimer during a hearing in 1954.

In his later years, Fermi continued teaching at the University of Chicago. He helped start what is now the Enrico Fermi Institute. His students included future Nobel winners like Owen Chamberlain and Tsung-Dao Lee. Fermi did important research on pions and muons, which are tiny particles. He also thought that cosmic rays came from material sped up by magnetic fields in space.

Fermi also thought about what is now called the "Fermi paradox." This is the puzzle of why, if there are so many planets, we haven't found any signs of alien life.

Fermi died of stomach cancer in his Chicago home on November 28, 1954, at age 53. He had suspected that working near the nuclear pile was risky. Two of his student assistants who worked near the pile also died of cancer.

A memorial service was held at the University of Chicago. Colleagues spoke about losing one of the world's "most brilliant and productive physicists." He was buried at Oak Woods Cemetery.

Fermi's Impact

Fermi received many awards, including the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1938. He was also given the Medal for Merit in 1946 for his work on the Manhattan Project. In 1999, Time magazine named Fermi one of the top 100 people of the twentieth century.

Fermi was known as a great teacher. He was very detailed and prepared his lectures carefully. His lecture notes were even turned into books. His papers and notebooks are now kept at the University of Chicago. Another physicist, Victor Weisskopf, said Fermi "always managed to find the simplest and most direct approach." Fermi disliked complicated theories. He was famous for getting quick and accurate answers to difficult problems. His method of making quick estimates is now called the "Fermi method" and is widely taught.

Fermi often said that when Alessandro Volta was working with electricity, he had no idea where his studies would lead. Fermi is mostly remembered for his work on nuclear power and weapons, especially building the first nuclear reactor. His scientific work, like his theory of beta decay and his work with slow neutrons, is still important today. His ideas about particles helped lead to the discovery of quarks.

Things Named After Fermi

Many things are named after Enrico Fermi. These include the Fermilab particle accelerator in Illinois, renamed in his honor in 1974. The Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope was named after him in 2008 because of his work on cosmic rays.

Three nuclear power plants are named after him: Fermi 1 and Fermi 2 in Michigan, and the Enrico Fermi Nuclear Power Plant in Italy. A synthetic element, fermium, was named after him. This makes him one of 16 scientists who have elements named after them.

Since 1956, the United States Atomic Energy Commission has given out the Fermi Award. This is its highest honor. Famous winners include Otto Hahn and Robert Oppenheimer.

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Enrico Fermi para niños

In Spanish: Enrico Fermi para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |