John Archibald Wheeler facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Archibald Wheeler

|

|

|---|---|

Wheeler before the Hermann Weyl-Conference 1985 in Kiel, Germany

|

|

| Born | July 9, 1911 Jacksonville, Florida, United States

|

| Died | April 13, 2008 (aged 96) Hightstown, New Jersey, United States

|

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | Johns Hopkins University (PhD) |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) | Janette Hegner |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Theory of the dispersion and absorption of helium (1933) |

| Doctoral advisor | Karl Herzfeld |

| Doctoral students |

|

John Archibald Wheeler (July 9, 1911 – April 13, 2008) was a famous American theoretical physicist. He helped bring back interest in general relativity in the United States after World War II. Wheeler also worked with Niels Bohr to explain nuclear fission. This is how atoms split apart.

He is well-known for making terms like "black hole" popular. He also came up with "quantum foam", "neutron moderator", "wormhole", and "it from bit". He even suggested the idea of a "one-electron universe". The famous physicist Stephen Hawking called him the "hero of the black hole story".

Wheeler earned his PhD from Johns Hopkins University. He then studied with other top scientists like Gregory Breit and Niels Bohr. During World War II, he joined the Manhattan Project. This project built the first nuclear weapons. He helped design and build nuclear reactors. After the war, he helped design the hydrogen bomb.

For most of his career, Wheeler was a professor of physics at Princeton University. He taught there from 1938 until 1976. He guided 46 PhD students, more than any other physics professor at Princeton. After leaving Princeton, he directed the Center for Theoretical Physics at the University of Texas at Austin. He retired in 1986.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Wheeler was born in Jacksonville, Florida, on July 9, 1911. His parents, Joseph Lewis Wheeler and Mabel Archibald Wheeler, were librarians. He was the oldest of four children. His two younger brothers, Joseph and Robert, and his younger sister, Mary, also became successful.

The family lived in Youngstown, Ohio. For one year, from 1921 to 1922, they lived on a farm in Benson, Vermont. John went to a one-room school there. After returning to Youngstown, he attended Rayen High School.

After high school, Wheeler received a scholarship to Johns Hopkins University in 1926. He published his first science paper in 1930. He earned his doctorate degree in 1933. His research was about how Helium atoms absorb and spread light.

He then received a fellowship to study with Gregory Breit and Niels Bohr. In 1934, Breit and Wheeler introduced the Breit–Wheeler process. This idea suggested that photons (light particles) could turn into matter. Specifically, they could become electron-positron pairs.

Starting His Career in Physics

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill hired Wheeler as a professor in 1937. But he wanted to work more closely with experts in particle physics. In 1938, he chose to become an assistant professor at Princeton University. Even though it was a lower position, he felt Princeton was a better choice for his career. He stayed at Princeton until 1976.

In 1937, Wheeler introduced the idea of the S-matrix. This was a mathematical tool to describe how particles scatter. Later, Werner Heisenberg developed this idea further. The S-matrix became very important in particle physics.

Wheeler also worked with Edward Teller to study Niels Bohr's liquid drop model of the atomic nucleus. This model helps explain how atoms behave. In 1939, Bohr brought news of nuclear fission to America. This was the discovery that atoms could be split.

Bohr and Wheeler quickly worked together to use the liquid drop model to explain nuclear fission. They wrote several papers on the topic. Their first paper was published on September 1, 1939. This was the same day Germany invaded Poland, starting World War II.

Wheeler also had a fascinating idea in 1940. He thought that positrons were just electrons traveling backward in time. This led him to propose the "one-electron universe". His student, Richard Feynman, found this hard to believe. But Feynman used the idea of time's reversibility in his famous Feynman diagrams.

Working on Nuclear Weapons

The Manhattan Project

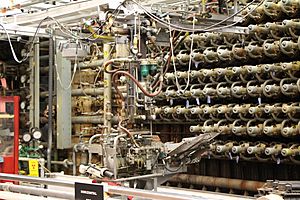

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, the United States entered World War II. Wheeler joined the Manhattan Project. This was a secret project to build nuclear weapons. He moved to the University of Chicago in January 1942. There, he helped design nuclear reactors. He also gave the name "neutron moderator" to a part of the reactor. Before that, it was called a "slower downer".

The United States Army Corps of Engineers then put DuPont in charge of building the reactors. Wheeler worked closely with DuPont engineers. He moved his family to Wilmington, Delaware, and then to Richland, Washington. In Washington, he worked at the Hanford Site. This site was built to produce plutonium.

Wheeler was worried that some byproducts of nuclear fission could stop the reactor. These "poisons" would absorb the neutrons needed for the chain reaction. On September 15, 1944, the first reactor, the B Reactor, unexpectedly shut down. Wheeler quickly figured out that xenon-135 was the problem. This element was a strong "poison" that absorbed neutrons. They fixed the problem by adding more fuel.

Wheeler had a personal reason for working on the project. His brother Joe was fighting in Italy. Joe sent him a postcard saying, "Hurry up". Sadly, Joe was killed in October 1944. Wheeler later wrote that he couldn't stop thinking that the war could have ended sooner.

Developing the Hydrogen Bomb

In August 1945, Wheeler returned to Princeton. He continued his academic work. He explored physics ideas with his student, Richard Feynman. He also studied muons, which are particles similar to electrons.

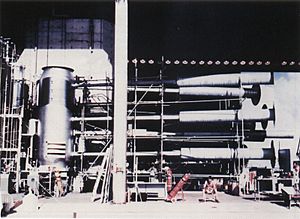

In 1949, the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb. This made the United States start a big effort to build a more powerful hydrogen bomb. Henry D. Smyth, Wheeler's boss at Princeton, asked him to join. Many physicists were hesitant. But Wheeler agreed after talking with Niels Bohr. Two of his students, Ken Ford and John Toll, joined him at Los Alamos Laboratory.

At Los Alamos, Wheeler and his family lived in a house once used by Robert Oppenheimer. In 1950, there was no good design for a hydrogen bomb. But in January 1951, Stanisław Ulam came up with a workable design.

In 1951, Wheeler started a branch of the Los Alamos lab at Princeton. It was called Project Matterhorn. One part, Matterhorn S, studied nuclear fusion for power. The other part, Matterhorn B, worked on nuclear weapons. Wheeler staffed it with young students. Their work led to the successful Ivy Mike nuclear test in the Pacific on November 1, 1952. Wheeler witnessed this huge explosion.

In 1953, Wheeler accidentally lost a secret paper about the hydrogen bomb design. He received an official warning for this. Project Matterhorn B was stopped, but Matterhorn S became the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory.

Later Career in Science

After Project Matterhorn, Wheeler went back to his academic work. In 1955, he studied the idea of a "geon". This was a theoretical idea of light or gravity waves held together by their own energy. He called it a "gravitational electromagnetic entity".

Geometrodynamics and Quantum Foam

In the 1950s, Wheeler developed "geometrodynamics". This was a way to explain all physical events, like gravity and electromagnetism, using the shapes of space-time. He imagined the universe's fabric as a chaotic, tiny realm of quantum fluctuations. He called this "quantum foam".

Understanding Black Holes and Wormholes

General relativity was not a very popular field of physics for a while. But Wheeler helped bring it back to life. He led a group at Princeton University. Wheeler and his students made big contributions to this field.

In 1957, Wheeler introduced the word "wormhole". He used it to describe hypothetical "tunnels" in space-time. These tunnels could connect different parts of the universe. He also worked on the theory of gravitational collapse. This is how massive stars can collapse. In 1967, he used the term "black hole" during a talk. He said someone in the audience suggested it because they were tired of hearing him say "gravitationally completely collapsed object".

Wheeler also helped develop the Wheeler–DeWitt equation in 1967. This equation is important in quantum gravity. Stephen Hawking later said it describes the "wave function of the Universe".

Quantum Information and Delayed Choice

Wheeler left Princeton University in 1976. He then became the director of the Center for Theoretical Physics at the University of Texas at Austin. He retired in 1986.

He proposed several "thought experiments" in quantum physics. One famous one is Wheeler's delayed choice experiment. These experiments try to figure out if light "knows" how it will be measured. Does it decide to act like a wave or a particle before we even observe it? Or does it only decide when we ask it a "question" through our experiment?

Teaching and Mentoring

Wheeler was a dedicated teacher. He taught many students who became famous physicists. Some of them include Richard Feynman, Kip Thorne, and Hugh Everett. Wheeler believed teaching young minds was very important. He supervised 46 PhD students at Princeton.

He also wrote important textbooks. With Kip Thorne and others, he wrote Gravitation (1973). This book was very influential for a whole generation of physicists. He also teamed up with Edwin F. Taylor to write Spacetime Physics (1966) and Scouting Black Holes (1996).

The Participatory Anthropic Principle

Wheeler had a unique idea about reality. He thought that reality is created by observers in the universe. He wondered, "How does something arise from nothing?" He also came up with the term "Participatory Anthropic Principle" (PAP).

In 1990, Wheeler suggested that information is a basic part of the universe's physics. To explain his PAP idea, Wheeler used a game similar to Twenty Questions. In his version, called Negative Twenty Questions, the person answering doesn't pick an object beforehand. They just give "Yes" or "No" answers that are consistent. This shows how the questions we ask might shape the answers we get. Wheeler's theory was that our consciousness might play a role in bringing the universe into existence.

Against Pseudoscience

In 1979, Wheeler spoke to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). He asked them to remove parapsychology (the study of psychic phenomena). He called it a pseudoscience. He believed that scientific organizations should only support research that can be proven with clear tests.

Personal Life

Wheeler was married to Janette Hegner for 72 years. She was a teacher and social worker. They got engaged quickly but waited to marry until he returned from Europe. They married on June 10, 1935. They had three children: Letitia, James English, and Alison.

They were founding members of the Unitarian Church of Princeton. Janette also started the Friends of the Princeton Public Library. In their later years, Janette traveled with him for his work. She passed away in October 2007 at age 96.

Death and Legacy

Wheeler received many awards and honors for his work. These included the Enrico Fermi Award in 1968, the National Medal of Science in 1971, and the Wolf Prize in Physics in 1997. He was a member of several important scientific groups. He also received honorary degrees from 18 different universities. In 2001, Princeton University created a special professorship in his honor. The University of Texas also named a lecture hall after him.

John Archibald Wheeler died on April 13, 2008, from pneumonia. He was 96 years old.

See also

In Spanish: John Archibald Wheeler para niños

In Spanish: John Archibald Wheeler para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |