Niels Bohr facts for kids

Niels Henrik David Bohr (born October 7, 1885 – died November 18, 1962) was a Danish physicist who made huge contributions to our understanding of how atoms are built and how quantum theory works. For his amazing work, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. Bohr was also a deep thinker (a philosopher) and loved to encourage scientific research.

Bohr created the famous Bohr model of the atom. In this model, he suggested that electrons orbit the atom's center (the nucleus) in specific energy levels, like planets around the sun. He also said that electrons could jump from one energy level to another. Even though newer models have replaced Bohr's, his basic ideas are still very important. He also came up with the idea of complementarity. This means that some things, like light, can act in two opposite ways at the same time, for example, as a wave or as tiny particles. This idea of complementarity was very important in Bohr's scientific and philosophical thinking.

Bohr started the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of Copenhagen, which is now called the Niels Bohr Institute. It opened in 1920 and became a famous place where many top physicists came to work and learn. Bohr helped and worked with many scientists, including Werner Heisenberg. He even predicted a new element similar to zirconium, which was later named hafnium after Copenhagen. Later, another element, bohrium, was named after him!

In the 1930s, Bohr helped many scientists who were escaping from Nazism in Germany. When Germany took over Denmark in 1940, Bohr had a famous meeting with Heisenberg, who was leading Germany's nuclear weapon project. In 1943, Bohr had to escape to Sweden because he was in danger of being arrested by the Germans. From Sweden, he flew to Britain and then joined the British and American efforts to build nuclear weapons, known as the Manhattan Project. After the war, Bohr strongly believed that countries should work together on nuclear energy. He also helped create CERN, a big science research center in Europe.

Quick facts for kids

Niels Bohr

|

|

|---|---|

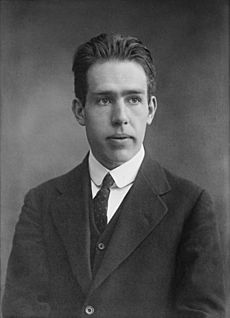

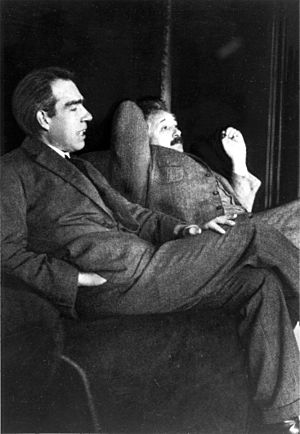

Bohr in 1922

|

|

| Born |

Niels Henrik David Bohr

7 October 1885 Copenhagen, Denmark

|

| Died | 18 November 1962 (aged 77) Copenhagen, Denmark

|

| Resting place | Assistens Cemetery |

| Alma mater | University of Copenhagen |

| Known for |

Bohr magneton

Bohr model Bohr radius Bohr–Einstein debates Bohr–Kramers–Slater theory Bohr–Van Leeuwen theorem Bohr–Sommerfeld theory Complementarity Copenhagen interpretation |

| Spouse(s) |

Margrethe Nørlund

(m. 1912) |

| Children | 6; including Aage and Ernest |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physics (1922)

Hughes Medal (1921)

Matteucci Medal (1923) Franklin Medal (1926) Foreign Member of the Royal Society (1926) Max Planck Medal (1930) Faraday Lectureship Prize (1930) Copley Medal (1938) Order of the Elephant (1947) Atoms for Peace Award (1957) Sonning Prize (1957) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theoretical physics |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Studies on the Electron Theory of Metals (1911) |

| Doctoral advisor | Christian Christiansen |

| Other academic advisors | |

| Doctoral students | Hendrik Kramers I. H. Usmani |

| Other notable students | Lev Landau |

| Influences |

|

| Influenced | |

| Signature | |

Contents

Early Life and Education

Niels Henrik David Bohr was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, on October 7, 1885. He was the second of three children. His father, Christian Bohr, was a professor of physiology at the University of Copenhagen. His mother, Ellen Adler, came from a wealthy Jewish family. Niels had an older sister, Jenny, and a younger brother, Harald. Jenny became a teacher, and Harald became a famous mathematician and footballer. Harald even played for the Danish national team in the 1908 Summer Olympics. Niels also loved football and played as a goalkeeper for a Copenhagen team.

Bohr started school at Gammelholm Latin School when he was seven. In 1903, he began studying at the University of Copenhagen. He focused on physics, learning from Professor Christian Christiansen. He also studied astronomy, mathematics, and philosophy.

In 1905, a competition was held by the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters. It asked scientists to study a way to measure the surface tension of liquids. Bohr did many experiments in his father's lab, as the university didn't have its own physics lab. He even had to make his own glass tools for the experiments! He improved the original method and won the gold medal for his work.

Bohr's brother Harald earned his master's degree in mathematics in 1909. Niels took a bit longer, earning his master's in 1911. His master's paper was about the theory of electrons in metals. He then expanded this into his much larger PhD thesis. His thesis was very important, but not many people outside of Denmark knew about it because it was written in Danish.

In 1910, Bohr met Margrethe Nørlund. They got married in 1912 and had six sons. Sadly, their oldest son, Christian, died in a boating accident in 1934. Another son, Harald, had severe mental disabilities and died young. However, their son Aage Bohr also became a successful physicist and won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1975, just like his father! Another son, Ernest, became an Olympic athlete in field hockey, like his uncle Harald.

Discoveries in Physics

The Bohr Model of the Atom

In 1911, Bohr traveled to England, where many important ideas about atoms were being developed. He met famous scientists like J. J. Thomson and Ernest Rutherford. Rutherford had recently proposed that atoms have a small, dense center called a nucleus. Bohr was very interested in this idea.

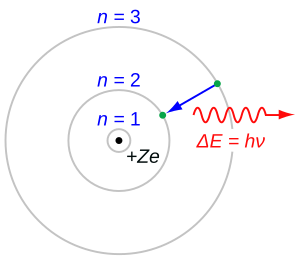

Bohr returned to Denmark in 1912. In 1913, he published three important papers, often called "the trilogy." In these papers, he combined Rutherford's idea of the atomic nucleus with Max Planck's quantum theory. This led to his famous Bohr model of the atom.

Bohr's model suggested that electrons orbit the nucleus in specific, stable paths called "stationary states." He also introduced the idea that an electron could jump from a higher-energy orbit to a lower one. When it did this, it would release a specific amount of energy as light. This idea helped explain why atoms give off light in specific colors, which scientists had observed but couldn't explain.

Many older physicists didn't like Bohr's new ideas at first. But younger scientists, including Rutherford and Albert Einstein, saw it as a major breakthrough. The Bohr model was successful because it could explain things that other models couldn't and predict new results that experiments later proved true. Today, the Bohr model is still the most well-known model of the atom and is often taught in high school science classes.

The Niels Bohr Institute

In 1917, Bohr began working to create an Institute of Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen. He got support from the Danish government and private donors. The institute, now known as the Niels Bohr Institute, opened on March 3, 1921, with Bohr as its director. His family even lived in an apartment on the first floor!

The Niels Bohr Institute became a very important place for scientists studying quantum mechanics in the 1920s and 1930s. Many of the world's best theoretical physicists came to work with Bohr. He was known as a kind host and a brilliant colleague.

The Bohr model worked well for simple atoms like hydrogen, but it struggled with more complex elements. In 1924, Wolfgang Pauli discovered the Pauli exclusion principle, which helped explain how electrons fill orbits in atoms. Using this, Bohr was able to predict that element 72, which hadn't been found yet, would be similar to zirconium, not a rare-earth element. Two scientists at the Institute, Dirk Coster and George de Hevesy, proved Bohr right. They found the element, which they named hafnium (Hafnia is the Latin name for Copenhagen).

In 1922, Bohr received the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on the structure of atoms and the light they give off. His Nobel lecture explained his ideas, including the correspondence principle. This principle says that quantum theory matches classical physics when dealing with very large systems.

Understanding Quantum Mechanics

In 1927, Bohr became convinced that light could act as both waves and particles. Experiments also showed that matter, like electrons, could behave like waves too. This led him to develop the idea of complementarity. This principle states that things can have two seemingly opposite properties at the same time, depending on how you observe them. For example, an electron can act as a wave or a particle, but you can't observe both properties at once.

In 1927, Werner Heisenberg developed the uncertainty principle. This principle says that you can't know both the exact position and the exact speed of a particle at the same time. The more accurately you know one, the less accurately you can know the other. Bohr and Albert Einstein had many friendly arguments about these new ideas in quantum physics throughout their lives. Einstein preferred the older, more predictable classical physics, while Bohr embraced the new, more probabilistic quantum physics.

In 1932, Bohr and his family moved into the Carlsberg Honorary Residence, a mansion given to famous Danes for their contributions to science or arts.

In 1936, Bohr developed a new theory called the compound nucleus model. This model explained how neutrons could be captured by an atom's nucleus. He imagined the nucleus like a drop of liquid that could change shape.

When Otto Hahn discovered nuclear fission in 1938 (the splitting of an atom's nucleus), it created a lot of excitement. Bohr brought this news to the United States in 1939. Based on his liquid drop model, Bohr quickly realized that it was the uranium-235 isotope, not the more common uranium-238, that was responsible for fission with slow neutrons. This was a very important discovery for understanding nuclear energy.

Philosophy and World War II

Helping Refugees

When Nazism grew strong in Germany, many scientists, especially Jewish ones, had to leave their homes. In 1933, Bohr helped these refugee academics by offering them temporary jobs at his institute, giving them money, and finding them places at universities around the world. He helped many famous scientists escape danger.

When Nazi Germany invaded and occupied Denmark in April 1940, Bohr took action to protect the gold Nobel medals of two German scientists, Max von Laue and James Franck. He had a colleague dissolve them in a special acid called aqua regia. This way, the Germans wouldn't find the gold. After the war, the gold was recovered, and the medals were remade.

Meeting with Heisenberg

Bohr knew that uranium-235 could be used to make an atomic bomb, but he didn't think it was possible to get enough of it. In September 1941, Werner Heisenberg, who was leading Germany's nuclear energy project, visited Bohr in Copenhagen. They had a private conversation that has been much debated. Heisenberg later said he wanted to talk about the moral responsibilities of scientists regarding nuclear weapons. Bohr, however, later wrote that he was shocked by Heisenberg's belief that Germany would win the war and that atomic weapons could be decisive.

This meeting has been explored in plays and films, showing how important and mysterious it was.

Escape and the Manhattan Project

In September 1943, Bohr and his family learned that the Nazis considered them Jewish and they were in danger of being arrested. The Danish resistance helped Bohr and his wife escape by sea to Sweden. The next day, Bohr convinced the King of Sweden to publicly offer safety to Jewish refugees. This led to the amazing rescue of the Danish Jews by their countrymen, where over 7,000 Danish Jews escaped to Sweden.

When the British heard about Bohr's escape, they flew him to Britain in a special high-speed bomber plane. Bohr had to lie in the plane's bomb bay and almost passed out from lack of oxygen during the flight! His son Aage joined him a week later as his assistant.

Bohr was kept secret in Britain and then traveled to the United States in December 1943 to join the Manhattan Project, the secret American project to build nuclear weapons. For safety, he used the name "Nicholas Baker." He visited scientists at different labs, including Los Alamos, where the bombs were being designed.

Bohr didn't stay at Los Alamos all the time, but he made many visits. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the head of Los Alamos, said Bohr was like a "scientific father figure" to the younger scientists. Bohr quickly realized that nuclear weapons would completely change how countries interacted. He believed that the project should be shared with the Soviet Union to prevent a nuclear arms race. He met with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt to discuss this, but they disagreed with his idea of sharing the information.

In June 1950, Bohr wrote an "Open Letter" to the United Nations, asking for international cooperation on nuclear energy. His ideas later helped create the International Atomic Energy Agency. In 1957, he received the first ever Atoms for Peace Award.

Later Years and Legacy

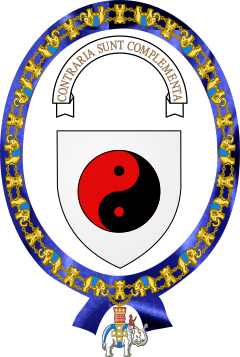

After the war, Bohr returned to Copenhagen in 1945. In 1947, the new King of Denmark, Frederick IX, gave Bohr the Order of the Elephant, a very high honor usually given only to royalty. Bohr designed his own coat of arms for this honor, which included the taijitu (yin and yang symbol) and the Latin motto Contraria sunt complementa, meaning "opposites are complementary." This motto reflected his scientific idea of complementarity.

The Second World War showed that science, especially physics, needed a lot of money and resources. To keep talented scientists in Europe, twelve European countries created CERN, a research organization for big science projects. Bohr supported CERN, and it became a major center for physics research.

In 1957, Scandinavian countries formed the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics, with Bohr as its chairman. He also helped found the Research Establishment Risø of the Danish Atomic Energy Commission.

Niels Bohr died of heart failure at his home in Copenhagen on November 18, 1962. He was cremated, and his ashes were buried in the family plot in the Assistens Cemetery. On what would have been his 80th birthday, October 7, 1965, the Institute for Theoretical Physics at the University of Copenhagen was officially renamed the Niels Bohr Institute.

Accolades

Bohr received many awards and honors throughout his life. Besides the Nobel Prize, he also received the Hughes Medal in 1921, the Matteucci Medal in 1923, the Franklin Medal in 1926, the Copley Medal in 1938, the Order of the Elephant in 1947, the Atoms for Peace Award in 1957, and the Sonning Prize in 1961. He became a member of many important scientific societies around the world.

Denmark honored Bohr on a postage stamp in 1963, showing him, the hydrogen atom, and a physics formula. In 1997, his portrait appeared on the Danish 500-krone banknote. On his 127th birthday in 2012, Google featured the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom as a Google Doodle. An asteroid, 3948 Bohr, a lunar crater, Bohr, and the chemical element bohrium (atomic number 107) are all named after him.

See also

In Spanish: Niels Bohr para niños

In Spanish: Niels Bohr para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |