Max Delbrück facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Max Delbrück

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Max Ludwig Henning Delbrück

September 4, 1906 |

| Died | March 9, 1981 (aged 74) |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | University of Göttingen |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse(s) | Mary Bruce |

| Children | Four |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Emmi Bonhoeffer (sister) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biophysics |

| Institutions | Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry Vanderbilt University Caltech |

| Doctoral advisor | Lise Meitner |

| Doctoral students | Lily Jan, Yuh Nung Jan, Ernst Peter Fischer, Charles M. Steinberg |

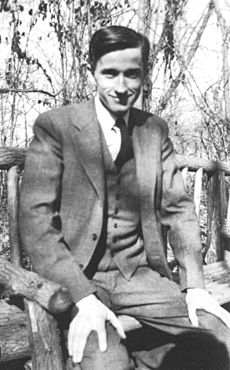

Max Ludwig Henning Delbrück (September 4, 1906 – March 9, 1981) was a German–American biophysicist. He helped start the field of molecular biology in the late 1930s. This field studies living things at a very small, molecular level.

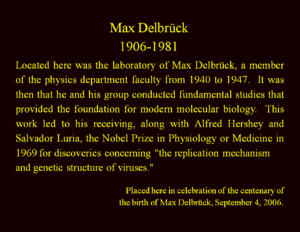

Max Delbrück encouraged physicists to become interested in biology. He especially wanted them to understand genes, which were a mystery at the time. In 1945, he formed the Phage Group with Salvador Luria and Alfred Hershey. This group made big discoveries about genetics. The three scientists shared the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. They won for their work on how viruses copy themselves and how their genes are structured.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Max Delbrück was born in Berlin, German Empire. His mother was the granddaughter of Justus Liebig, a famous chemist. His father, Hans Delbrück, was a history professor at the University of Berlin.

In 1937, Delbrück left Nazi Germany and moved to America. He first lived in California, then in Tennessee. He became a US citizen in 1945. In 1941, he married Mary Bruce, and they had four children.

Max's brother, Justus, and his sister, Emmi Bonhoeffer, were part of the resistance movement against the Nazis. His brothers-in-law, Klaus Bonhoeffer and Dietrich Bonhoeffer, were also involved.

Education and Early Career

Delbrück first studied astrophysics at the University of Göttingen. He then switched to theoretical physics. After earning his Ph.D. in 1930, he traveled to England, Denmark, and Switzerland. During his travels, he met famous scientists like Wolfgang Pauli and Niels Bohr. They helped him become interested in biology.

In 1932, Delbrück returned to Berlin. He worked as an assistant to Lise Meitner, who was studying uranium with neutrons. In 1933, Delbrück wrote a paper about gamma rays scattering. This phenomenon was later confirmed and named "Delbrück scattering" by Hans Bethe.

In 1935, Delbrück worked with Nikolay Timofeev-Ressovsky and Karl Zimmer. They published an important paper called Über die Natur der Genmutation und der Genstruktur. This work greatly improved the understanding of how genes change and are structured. It was a key step in forming the field of molecular genetics. This paper also inspired Erwin Schrödinger to write his famous book What Is Life?

Research on Viruses and Genes

In 1937, Delbrück received a special grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. This foundation was helping to start the molecular biology research program. Delbrück used the grant to study the genetics of fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster) at Caltech. There, he combined his interests in biochemistry and genetics.

While at Caltech, Delbrück began studying bacteria and their viruses, called phages. In 1939, he and Emory Ellis published a paper called "The growth of bacteriophage." They reported that viruses reproduce in "one step," not by growing slowly like other living cells.

After his grant ended in 1939, Delbrück moved to Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. From 1940 to 1947, he taught physics but had his lab in the biology department. In 1941, he met Salvador Luria from Indiana University. Luria often visited Delbrück at Vanderbilt.

In 1942, Delbrück and Luria published their famous Luria–Delbrück experiment. This experiment showed that bacteria become resistant to virus infection because of random mutations. This means that changes in their genes happen by chance, not because the bacteria try to adapt. Alfred Hershey also joined them in 1943.

The Luria–Delbrück experiment was very important. It showed that Darwin's idea of natural selection acting on random mutations applies to bacteria, just like it does to more complex organisms. This experiment helped prove that evolution is not planned. Instead, organisms have natural differences, and those differences that help them survive are passed on. This work was a big part of why Delbrück and Luria won the 1969 Nobel Prize.

The Phage Group and Nobel Prize

In 1945, Delbrück, Luria, and Hershey started a course on bacteriophage genetics at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Long Island, New York. This group, known as the Phage Group, played a huge role in the early development of molecular biology.

Max Delbrück, Salvador Luria, and Alfred Hershey shared the 1969 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. They were honored "for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses." The Nobel committee especially praised Delbrück for turning bacteriophage research into an exact science. He set up the rules for precise measurements and statistical analysis.

In late 1947, Delbrück returned to Caltech as a biology professor. He stayed there for the rest of his career. He also helped set up an institute for molecular genetics at the University of Cologne in Germany.

Awards and Recognition

Besides the Nobel Prize, Delbrück received many other honors.

- He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1967.

- He became an EMBO Member in 1970.

- The American Physical Society awards the Max Delbruck Prize (formerly the biological physics prize) in his honor.

- The Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association in Berlin, Germany, is also named after him.

Later Life and Legacy

Max Delbrück greatly encouraged physicists to study biology. His ideas about how genes can mutate influenced physicist Erwin Schrödinger. Schrödinger wrote in his 1944 book What Is Life? that genes might be like a special "aperiodic crystal" that stores codes. This idea later influenced scientists like Rosalind Franklin, Francis Crick, and James Watson when they discovered the double helix structure of DNA in 1953.

In 1977, Delbrück retired from Caltech. He became interested in how living things behave and studied mold behavior for a while.

Max Delbrück passed away on March 9, 1981, at the age of 74, in Pasadena, California. In 2006, on what would have been his 100th birthday, his family and friends gathered at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory to remember his life and work.

See also

In Spanish: Max Delbrück para niños

In Spanish: Max Delbrück para niños