Wolfgang Pauli facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli

|

|

|---|---|

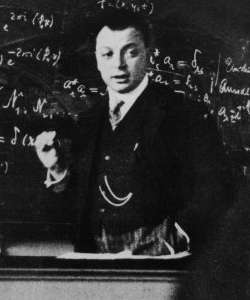

Pauli in 1945

|

|

| Born |

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli

25 April 1900 |

| Died | 15 December 1958 (aged 58) Zurich, Switzerland

|

| Citizenship | Austria United States Switzerland |

| Alma mater | Ludwig-Maximilians University |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theoretical physics |

| Institutions | University of Göttingen University of Copenhagen University of Hamburg ETH Zurich Institute for Advanced Study |

| Thesis | About the Hydrogen Molecular Ion Model (1921) |

| Doctoral advisor | Arnold Sommerfeld |

| Other academic advisors | Max Born |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Other notable students |

|

| Influences |

|

| Influenced |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

| Notes | |

|

His godfather was Ernst Mach. He is not to be confused with Wolfgang Paul, who called Pauli his "imaginary part", a pun with the imaginary unit i.

|

|

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli (born April 25, 1900 – died December 15, 1958) was an Austrian theoretical physicist. He was one of the first scientists to explore quantum physics. This field studies how tiny particles like atoms and electrons behave.

In 1945, Pauli won the Nobel Prize in Physics. He received it for discovering a key rule of nature: the Pauli exclusion principle. This principle helps us understand how matter is built. It explains how electrons behave in atoms.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Pauli was born in Vienna, Austria. His father was a chemist, and his mother was Bertha Camilla Schütz. His middle name honored his godfather, physicist Ernst Mach. Pauli's family background included Jewish and Roman Catholic roots. He was raised Catholic but later left the Church.

He was a brilliant student from a young age. He finished high school in Vienna with top honors in 1918. Just two months later, he published his first scientific paper. It was about Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity.

Pauli then studied at the Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich. He worked with Arnold Sommerfeld, a famous physicist. In 1921, Pauli earned his PhD. His work focused on the quantum theory of ionized hydrogen.

Pauli's Career in Physics

After his PhD, Pauli was asked to write a review of relativity for a major encyclopedia. He completed this 237-page article in just two months. Even Albert Einstein praised it. This article became a standard reference for the topic.

Pauli worked at the University of Göttingen and then at the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Copenhagen. From 1923 to 1928, he was a professor at the University of Hamburg. During these years, he played a big part in developing modern quantum mechanics.

He created the Pauli exclusion principle, which is one of his most important discoveries. He also developed the theory of nonrelativistic spin. Spin describes a basic property of particles, like a tiny internal rotation.

In 1928, Pauli became a professor at ETH Zurich in Switzerland. He also taught as a visiting professor in the United States. He visited the University of Michigan in 1931 and the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in 1935.

Pauli and Carl Jung

In 1930, Pauli went through a difficult time. He had a personal crisis after his divorce and his mother's death. He decided to see Carl Jung, a famous psychiatrist and psychotherapist in Zurich. Jung helped Pauli by interpreting his dreams.

Pauli and Jung became close collaborators. Pauli even helped Jung refine some of his ideas, especially about synchronicity. Synchronicity is the idea of meaningful coincidences. Their discussions are recorded in their letters, published as Atom and Archetype.

Moving to the United States

In 1938, Austria was taken over by Germany. This made Pauli a German citizen, which caused problems for him during World War II. In 1940, he moved to the United States. He became a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study.

After the war, in 1946, Pauli became a U.S. citizen. He then returned to Zurich, Switzerland. He lived there for the rest of his life and became a Swiss citizen in 1949.

The Number 137

In 1958, Pauli became ill with pancreatic cancer. When his assistant visited him in the hospital, Pauli asked about his room number. It was 137. Pauli had always been fascinated by the number 137. This number is close to the value of the fine-structure constant. This constant is a fundamental number in physics that describes the strength of the electromagnetic force. Pauli died in that room on December 15, 1958.

Key Scientific Discoveries

Pauli made many important contributions to physics, especially in quantum mechanics. He often shared his ideas through letters with other scientists. These letters were copied and shared widely.

In 1921, Pauli worked with Niels Bohr to create the Aufbau Principle. This principle explains how electrons fill up energy shells around an atom's nucleus.

The Exclusion Principle

In 1924, Pauli proposed a new idea about electrons. He suggested that electrons have a special property with two possible values. This helped explain why atoms behave the way they do. He then developed the Pauli exclusion principle. This principle states that no two electrons in an atom can be in the exact same quantum state. This means they can't have the same four quantum numbers, including Pauli's new property.

A year later, other scientists identified this new property as electron spin. Spin is like a tiny internal rotation of an electron.

Quantum Mechanics and Neutrinos

In 1926, Pauli used a new theory called matrix theory to explain the spectrum of the hydrogen atom. This helped prove that the new quantum mechanics theory was correct.

He also introduced Pauli matrices. These are mathematical tools that help describe electron spin. This work influenced Paul Dirac in developing his famous equation for the relativistic electron.

In 1930, Pauli suggested the existence of a new, tiny, neutral particle. He called it the neutrino. He proposed it to explain how energy seemed to disappear during a process called beta decay. In 1934, Enrico Fermi included the neutrino in his theory of beta decay. The neutrino was finally confirmed by experiments in 1956, just two years before Pauli's death.

In 1940, Pauli worked on the spin-statistics theorem. This important rule in quantum field theory explains that particles with half-integer spin (like electrons) are called fermions. Particles with integer spin (like photons) are called bosons. They behave differently.

Pauli also developed a method called Pauli–Villars regularization. This technique helps physicists handle infinite values that appear in calculations in quantum field theory. It makes these calculations manageable.

Personality and Friendships

Pauli was known for something called the Pauli effect. This was a funny anecdote that experimental equipment would often break when he was nearby. Pauli found this amusing.

He was also famous for being a perfectionist. He expected high standards from his own work and from others. He was known as the "conscience of physics" because he would strongly criticize theories he found weak. He often called them ganz falsch, meaning "utterly wrong."

But his most severe criticism was for ideas that were so unclear they couldn't be tested. He famously said of one such paper: "It is not even wrong!" This meant the idea was so vague it wasn't even wrong, it was just meaningless in science.

Pauli had a strong personality, but he also formed close friendships with other physicists like Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg.

Pauli's Philosophy

In his discussions with Carl Jung, Pauli developed a unique idea. They believed there is a "psychophysically neutral reality." This means there's a deeper reality from which both our minds and the physical world come. Pauli thought that quantum physics hinted at this deeper order. He believed that both our thoughts and physical events are part of this cosmic order.

Pauli and Jung thought that common principles, called "archetypes," govern this reality. These principles can show up as psychological experiences or as physical events. They also believed that synchronicities (meaningful coincidences) might reveal how this underlying reality works.

Personal Life

In 1929, Pauli married Käthe Margarethe Deppner. Their marriage was short and ended in divorce. In 1934, he married Franziska Bertram. They did not have any children.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Wolfgang Pauli para niños

In Spanish: Wolfgang Pauli para niños