James Franck facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Franck

|

|

|---|---|

Franck in 1925

|

|

| Born | 26 August 1882 |

| Died | 21 May 1964 (aged 81) |

| Nationality | German |

| Citizenship | Germany United States |

| Alma mater | University of Heidelberg University of Berlin |

| Known for | Franck–Condon principle Franck–Hertz experiment Franck Report |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | University of Berlin University of Göttingen Johns Hopkins University University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory |

| Thesis | Über die Beweglichkeit der Ladungsträger der Spitzenentladung (1906) |

| Doctoral advisor | Emil Gabriel Warburg Paul Drude |

| Doctoral students | Wilhelm Hanle Arthur R. von Hippel Theodore Puck |

James Franck (born August 26, 1882 – died May 21, 1964) was a German physicist. He won the 1925 Nobel Prize for Physics with Gustav Hertz. They won for finding out how electrons hit atoms.

Franck finished his advanced studies in 1906 and became a university lecturer in 1911. He taught at the Frederick William University in Berlin until 1918. During World War I, he volunteered for the German Army. He was badly hurt in 1917 from a gas attack and received the Iron Cross.

After the war, Franck became a leader in physics research. In 1920, he became a full professor at the University of Göttingen. There, he worked on quantum physics with Max Born. Their work included the Franck–Hertz experiment, which helped prove the Bohr model of the atom. James Franck also helped many women become successful physicists, like Lise Meitner and Hertha Sponer.

When the Nazi Party took power in Germany in 1933, Franck quit his job. He did this to protest against unfair rules that fired Jewish scientists. He helped many scientists find new jobs outside Germany. In November 1933, he left Germany himself. After a year in Denmark, he moved to the United States. He worked at Johns Hopkins University and then the University of Chicago. During this time, he became very interested in photosynthesis.

During World War II, Franck worked on the Manhattan Project. This project developed the atomic bomb. He led the Chemistry Division at the Metallurgical Laboratory. He also led a group that wrote the Franck Report. This report suggested that the atomic bombs should not be used on Japanese cities without a warning.

Contents

Early Life and Education

James Franck was born in Hamburg, Germany, on August 26, 1882. He grew up in a Jewish family. His father, Jacob Franck, was a banker. His mother, Rebecca, came from a family of rabbis. James was the second child and first son.

In 1901, James started studying law and economics at the University of Heidelberg. He soon found he liked science much more. With help from his friend Max Born, he convinced his parents to let him study physics and chemistry. Since Heidelberg wasn't strong in science, he moved to the Frederick William University in Berlin.

In Berlin, Franck learned from famous scientists like Max Planck. For his PhD, he studied how electric charges move. He finished his studies in 1906. After his military service, he became an assistant at Frederick William University. In 1907, he married Ingrid Josephson, a Swedish pianist. They had two daughters, Dagmar and Elisabeth.

To become a university professor in Germany, scientists needed to do more research after their PhD. Franck published 34 scientific papers by 1914. He often worked with other scientists, especially Gustav Hertz. They wrote 19 papers together. In 1911, he officially qualified to teach at the university.

The Franck–Hertz Experiment

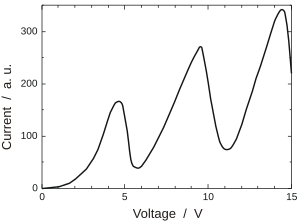

In 1914, Franck and Hertz did an important experiment. They wanted to understand how light is produced. They used a special glass tube with mercury vapor and energetic electrons. They found that when an electron hit a mercury atom, it always lost a specific amount of energy (4.9 electron volts).

Even if an electron was faster, it would still lose only that exact amount of energy. Slower electrons would just bounce off without losing much speed. These results were very important. They supported Albert Einstein's idea about the photoelectric effect. They also supported Niels Bohr's model of the atom.

Bohr's model said that electrons inside an atom can only exist at certain "energy levels." When an electron hits a mercury atom, it makes the atom's own electron jump to a higher energy level. This jump always needs exactly 4.9 electron volts. There were no energy levels in between.

In a later paper, Franck and Hertz showed that the mercury atoms then gave off ultraviolet light. The energy of this light matched the 4.9 electron volts that the flying electron had lost. This also matched Bohr's predictions. In 1926, Franck and Hertz received the 1925 Nobel Prize in Physics for their discovery.

World War I Service

James Franck joined the German Army when World War I started in August 1914. He served on the Western Front. In 1915, he became a lieutenant. He was part of a new unit that used chlorine gas as a weapon. He helped find places for these gas attacks.

He received the Iron Cross, Second Class, in 1915. The city of Hamburg also gave him the Hanseatic Cross in 1916. While recovering from an illness, he was appointed an assistant professor. He later worked on developing gas masks with other scientists. He received the Iron Cross, First Class, in 1918. He left the army after the war ended in November 1918.

After the war, Franck took a job at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. This allowed him to continue his research. He worked with younger scientists to study how electrons in atoms behave when excited. They even came up with the word "metastable" for atoms that stay in a higher energy state for a long time.

Leading Physics in Göttingen

In 1920, the University of Göttingen offered Max Born a top physics job. Born agreed to come if Franck could also lead experimental physics there. So, on November 15, 1920, Franck became a full professor and director of the Second Institute for Experimental Physics. He brought Hertha Sponer with him as an assistant. Franck used his own money to buy the newest lab equipment.

Between 1920 and 1933, Göttingen became one of the world's most important places for physics. Even though Born and Franck didn't publish many papers together, they discussed all their ideas. It was very hard to get into Franck's lab. Many students wanted to work with him.

Franck guided many students for their PhDs. He made sure their research topics were clear and taught them how to do original science. He also made sure they stayed within the lab's budget. Under his guidance, they studied the structure of atoms and molecules.

In his own research, Franck developed what is now called the Franck–Condon principle. This rule helps explain how molecules change energy levels when they absorb or release light. It says that changes are more likely if the molecule's energy waves overlap well. This principle is now used in many areas of science.

Life in Exile

This successful time ended when the Nazi Party came to power in Germany in March 1933. The new government made a law that forced Jewish government workers to retire or be fired. Even though Franck was a war veteran and exempt, he resigned on April 17, 1933. He said that science was like his God. He was proud of his Jewish background. He was the first professor to quit in protest. Newspapers worldwide reported his action, but no other governments or universities protested.

Franck helped other Jewish scientists who had been fired find jobs in other countries. He then left Germany in November 1933. After a short visit to the United States, he took a job at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark. He started working with Hilde Levi and became interested in photosynthesis. This is the process plants use to turn light, carbon dioxide, and water into food. He found biological processes much more complex than simple atomic reactions.

Franck wanted to make sure his daughters had financial security. He divided his Nobel Prize money between them. He gave his gold Nobel medal to Niels Bohr for safekeeping. When Germany invaded Denmark in 1940, another chemist, George de Hevesy, dissolved the gold medals (including Franck's) in acid. This was to stop the Germans from taking them. After the war, the gold was recovered, and the Nobel Society made new medals.

In 1935, Franck moved to the United States. He became a professor at Johns Hopkins University. The lab there was not as good as his old one in Göttingen. He also worried about his family still in Germany. He needed money to help them move. So, in 1938, he accepted a job at the University of Chicago. His work on photosynthesis was very interesting there.

At Chicago, he worked with Edward Teller and Hans Gaffron. His daughters and their families also moved to the United States. He even managed to bring his elderly mother and aunt. He became a naturalized U.S. citizen in July 1941. This meant he was not considered an "enemy alien" when the U.S. declared war on Germany.

In 1942, Arthur H. Compton started the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago. This was part of the Manhattan Project to build nuclear reactors and atomic bombs. Franck was asked to lead the Chemistry Division.

Franck also led a committee that looked at the social problems of the atomic bomb. This group included scientists like Leó Szilárd. In 1945, Franck warned that "mankind has learned to unleash atomic power without being ethically and politically prepared to use it wisely." The committee wrote the Franck Report. It suggested that the atomic bombs should not be used on Japanese cities without a warning. However, the government decided to use them anyway.

Later Life and Legacy

Franck married Hertha Sponer in 1946. His first wife, Ingrid, had passed away in 1942. In his later research, he continued to study how photosynthesis works.

Besides the Nobel Prize, Franck received other honors. He won the Max Planck medal in 1951 and the Rumford Medal in 1955 for his work on photosynthesis. He became an honorary citizen of Göttingen in 1953. In 1964, he was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society.

James Franck died suddenly from a heart attack on May 21, 1964, while visiting Göttingen. He was buried in Chicago next to his first wife.

In 1967, the University of Chicago named the James Franck Institute after him. A crater on the Moon has also been named in his honor. His important papers are kept at the University of Chicago Library.

See also

In Spanish: James Franck para niños

In Spanish: James Franck para niños

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |