Isidor Isaac Rabi facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Isidor Isaac Rabi

|

|

|---|---|

Rabi in 1944

|

|

| Chairman of the President's Science Advisory Committee | |

| In office 1956–1957 |

|

| President | Dwight D. Eisenhower |

| Preceded by | Lee DuBridge |

| Succeeded by | James Killian |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Israel Isaac Rabi

July 29, 1898 Rymanów, Galicia, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | January 11, 1988 (aged 89) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Riverside Cemetery (Saddle Brook, New Jersey) |

| Education |

|

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | On the principal magnetic susceptibilities of crystals (1927) |

| Doctoral advisor | Albert Potter Wills |

| Doctoral students | |

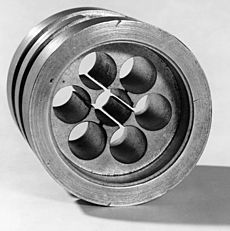

Isidor Isaac Rabi (born Israel Isaac Rabi, July 29, 1898 – January 11, 1988) was an American physicist. He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1944. He received this award for his discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance. This technology is now used in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Rabi was also one of the first scientists in the United States to work on the cavity magnetron. This device is important for microwave radar and microwave ovens.

Rabi was born into a Polish-Jewish family in Rymanów, Galicia. This area is now part of Poland. He moved to the United States as a baby and grew up in New York City. He first studied electrical engineering at Cornell University in 1916. He later switched to chemistry and then became very interested in physics. He continued his studies at Columbia University, where he earned his doctorate degree. After finishing his studies in 1927, he traveled to Europe. There, he met and worked with many of the best physicists of his time.

In 1929, Rabi returned to the United States. Columbia University offered him a teaching job. Working with Gregory Breit, he helped create the Breit–Rabi equation. He also predicted how the Stern–Gerlach experiment could be changed to learn more about the atomic nucleus. His methods for using nuclear magnetic resonance helped scientists find the magnetic moment and nuclear spin of atoms. These discoveries earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1944. Nuclear magnetic resonance became a key tool in physics and chemistry. Later, it led to the development of MRI, which is very important in medicine today.

During World War II, Rabi worked on radar at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He also helped with the Manhattan Project, which developed the first atomic bombs. After the war, he advised the United States Atomic Energy Commission. He was also a science advisor to President Dwight D. Eisenhower. Rabi helped create the Brookhaven National Laboratory in 1946. Later, as a US delegate to UNESCO, he helped create CERN in 1952. When Columbia University created a special teaching position called University Professor in 1964, Rabi was the first to receive it. He stopped teaching in 1967 but remained active in science until his death.

Contents

Early Life and His Path to Science

Isidor Isaac Rabi was born Israel Isaac Rabi on July 29, 1898. His family was from Rymanów, a town in Galicia. This region was then part of Austria-Hungary. When he was a baby, his father moved to the United States. Rabi and his mother joined him a few months later. They lived in a small apartment in New York City. At home, his family spoke Yiddish.

When Rabi started school, his mother told the school his name was Izzy. The school official thought it was short for Isidor and wrote that down. From then on, Isidor became his official name. Later, he started writing his name as Isidor Isaac Rabi. Most of his friends and family called him "Rabi." In 1907, his family moved to Brooklyn and opened a grocery store.

As a boy, Rabi loved science. He borrowed science books from the library and built his own radio. He even published a small paper about radio parts when he was in elementary school. He went to high school in Brooklyn and graduated in 1916. He then went to Cornell University to study electrical engineering. He soon changed his major to chemistry and later became very interested in physics. He earned his Bachelor of Science degree in 1919.

Rabi's University Studies and Discoveries

In 1922, Rabi went back to Cornell as a graduate student in chemistry. He started studying physics more seriously. In 1923, he met Helen Newmark, who would later become his wife. To be closer to her, he moved his studies to Columbia University. There, his professor suggested he study how certain crystals react to magnets.

Rabi found a new, easier way to measure how crystals respond to magnetic fields. This new method was also more accurate. He sent his research paper to a science magazine in July 1926. The next day, he married Helen. His work caught the attention of other scientists.

Like many young physicists, Rabi was excited by new discoveries happening in Europe. He was especially amazed by the Stern–Gerlach experiment. This experiment showed him that quantum mechanics was real. He worked with other scientists to understand how molecules behave. They used advanced math to solve complex physics problems.

Adventures in European Physics

In May 1927, Rabi received a special fellowship that allowed him to study in Europe. He wanted to work with famous physicists like Erwin Schrödinger and Arnold Sommerfeld. In Munich, he met other American physicists. He also worked with German physicists Rudolf Peierls and Hans Bethe.

Rabi then went to Copenhagen to work with Niels Bohr, another famous physicist. After that, he moved to Hamburg to work with Wolfgang Pauli. In Hamburg, he also met Otto Stern, who was doing experiments with molecular beams. Stern would later win a Nobel Prize for this work.

Molecular beam experiments used magnets to study atoms. Rabi came up with a new, simpler way to use magnets in these experiments. This new method made the results more accurate. Stern encouraged Rabi to share his findings. Rabi published his new method in science journals in 1929.

After his fellowship ended, Rabi and Helen moved to Leipzig. He hoped to work with Werner Heisenberg. There, he also met J. Robert Oppenheimer, who became a long-time friend. Rabi's time in Europe helped him learn a lot from the top minds in physics.

Developing the Molecular Beam Laboratory

On March 26, 1929, Columbia University offered Rabi a teaching job. He would earn $3,000 a year. Columbia needed someone to teach advanced physics, and Heisenberg had recommended Rabi. Helen was expecting their first child, so Rabi needed a steady job. He accepted the offer and returned to the United States. He was the only Jewish faculty member in Columbia's physics department at that time.

Rabi was not known as a great lecturer. Some students found his classes hard to follow. However, he inspired many students to become physicists. Several of his students went on to become famous scientists themselves.

Rabi's first daughter, Helen Elizabeth, was born in September 1929. His second daughter, Margaret Joella, was born in 1934. Even with his teaching duties and family, Rabi found time for research. He was promoted to assistant professor and then to full professor in 1937.

In 1931, Rabi started working on particle beam experiments again. With Gregory Breit, he developed the Breit-Rabi equation. This equation helped predict how to study the properties of the atomic nucleus. Rabi and his team built a special machine at Columbia to do these experiments. They used a weak magnetic field to study the nuclear spin of sodium.

Rabi's Molecular Beam Laboratory became a popular place for young scientists. Many talented students came to work there. One of them was Jerrold Zacharias, who suggested studying hydrogen, the simplest element. Harold Urey, who had just discovered deuterium (a type of hydrogen), provided them with special water for their experiments. Urey even shared half of his Nobel Prize money to help fund Rabi's lab.

In 1937, Rabi's team used a new method called nuclear magnetic resonance. They used it to measure the magnetic moment of different substances. They found that the magnetic moment of a proton was not what theory predicted. They also found that a deuteron (a nucleus made of a proton and a neutron) had an unusual shape. This discovery gave important clues about the strong force that holds atomic nuclei together. For creating this molecular-beam magnetic-resonance method, Rabi won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1944.

Rabi's Role in World War II Efforts

In September 1940, Rabi joined a science advisory group for the U.S. Army. Around this time, British scientists brought a new invention to the United States: the cavity magnetron. This device could create powerful microwaves, which were perfect for improving radar. American scientists realized this invention would change radar forever. A new lab was set up at MIT, called the Radiation Laboratory, to develop this technology.

Rabi volunteered to work at the Radiation Laboratory. His job was to study the magnetron, which was so secret it had to be kept in a safe. The scientists at the lab worked quickly to build a new microwave radar system. They faced many challenges but eventually succeeded. The magnetron was improved to make radar even more powerful. The lab developed many important radar systems, including air-to-surface radar and a long-range navigation system called LORAN. Rabi also helped set up a branch of the Radiation Laboratory at Columbia University.

In 1942, J. Robert Oppenheimer asked Rabi to join a secret project. This project was to build an atomic bomb at the Los Alamos Laboratory. Rabi and another scientist convinced Oppenheimer that the lab should be run by civilians, not the military. Rabi decided not to move to Los Alamos, but he became a consultant for the Manhattan Project. In July 1945, Rabi was present at the Trinity test, the first explosion of an atomic bomb. Scientists had a betting pool on how powerful the blast would be. Rabi bought the last remaining prediction, 18 kilotons. The actual blast was 18.6 kilotons, and Rabi won the pool!

Later Life and Contributions to Science Policy

After World War II, Rabi suggested that the magnetic properties of atoms could be used to build a very accurate clock. This idea led to the creation of atomic clocks, which are now used worldwide for precise timekeeping. Rabi continued his research on magnetic resonance until about 1960.

Rabi led Columbia's physics department from 1945 to 1949. During this time, the department was home to many brilliant scientists, including Nobel Prize winners and future Nobel laureates. In 1964, Columbia created a special position called University Professor, and Rabi was the first to receive it. This allowed him to research and teach whatever he wanted. He retired from teaching in 1967 but remained active in the department until his death. A special professorship was named after him in 1985.

After the war, there were many national laboratories, but none on the East Coast. Rabi and other scientists worked together to create a new national lab in New York. After much effort, nine universities joined forces. On January 31, 1947, the Brookhaven National Laboratory was officially established.

Rabi believed that science could help unite Europe after the war. In 1950, he became the US Delegate to UNESCO. At a meeting in Italy, he called for the creation of regional science labs in Europe. His efforts paid off. In 1952, representatives from eleven countries came together to create CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research. Rabi received letters from famous scientists thanking him for his work.

Advising the Government

The Atomic Energy Act of 1946 created a committee to advise the Atomic Energy Commission. Rabi was appointed to this committee in 1946. In 1950, the committee was against developing the hydrogen bomb. Rabi and Enrico Fermi even argued against it for moral reasons. However, President Harry S. Truman decided to go ahead with the bomb's development.

Rabi became the chairman of this committee in 1952 and served until 1956. He also advised President Dwight D. Eisenhower on science matters. In 1957, after the Soviet Union launched the Sputnik satellite, President Eisenhower asked Rabi for advice. Rabi suggested strengthening the science advisory committee to help the President quickly. This led to the creation of the President's Science Advisory Committee. Rabi also served on the NATO Science Committee.

Awards and Recognition

Rabi received many honors throughout his life. Besides the Nobel Prize, he received the Elliott Cresson Medal in 1942 and the Medal for Merit in 1948. He was also made an officer in the French Legion of Honour in 1956. Other awards included the Barnard Medal for Meritorious Service to Science in 1960, the Atoms for Peace Award in 1967, and the Oersted Medal in 1982. In 1985, he received the Public Welfare Medal. He was a member of many important scientific groups, including the American Physical Society, where he served as president in 1950. He was also a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

His Final Years

Isidor Isaac Rabi passed away at his home in New York City on January 11, 1988, from cancer. His wife, Helen, lived until 2005. In his last days, he was examined using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This technology was developed from his own groundbreaking research on magnetic resonance. He looked at the machine and said, "I saw myself in that machine... I never thought my work would come to this."

Books by Isidor Isaac Rabi

- Rabi, Isidor Isaac (1960). My Life and Times as a Physicist. Claremont, California: Claremont College. OCLC 1071412.

- Rabi, Isidor Isaac (1970). Science: The Center of Culture. New York: World Publishing Co.. OCLC 74630.

- Rabi, Isidor Isaac; Serber, Robert; Weisskopf, Victor F.; Pais, Abraham; Seaborg, Glenn T. (1969). Oppenheimer: The Story of One of the Most Remarkable Personalities of the 20th Century. Scribner's. OCLC 223176672.

See also

In Spanish: Isidor Isaac Rabi para niños

In Spanish: Isidor Isaac Rabi para niños

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |