J. Robert Oppenheimer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

J. Robert Oppenheimer

|

|

|---|---|

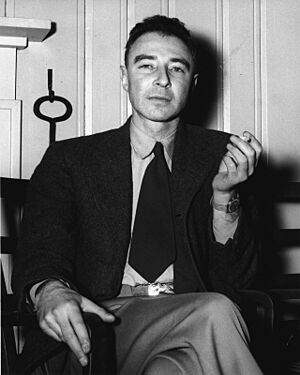

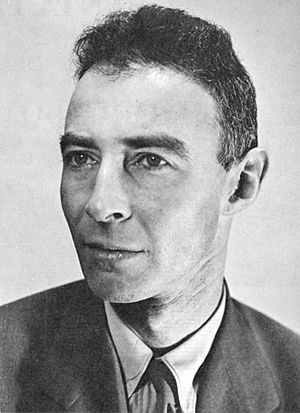

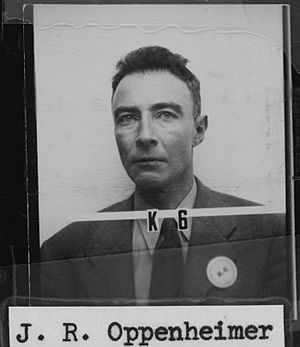

J. Robert Oppenheimer, c. 1944

|

|

| Born | April 22, 1904 |

| Died | February 18, 1967 (aged 62) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Harvard College Christ's College, Cambridge University of Göttingen |

| Known for | Nuclear weapons development Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit Oppenheimer–Phillips process Born–Oppenheimer approximation |

| Spouse(s) | Katherine "Kitty" Puening Harrison (1940–1967; his death; 2 children) |

| Awards | Enrico Fermi Award (1963) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theoretical physics |

| Institutions | University of California, Berkeley California Institute of Technology Los Alamos Laboratory Institute for Advanced Study |

| Thesis | Zur Quantentheorie kontinuierlicher Spektren (1927) |

| Doctoral advisor | Max Born |

| Doctoral students | Samuel W. Alderson David Bohm Robert Christy Sidney Dancoff Stan Frankel Willis Eugene Lamb Harold Lewis Philip Morrison Arnold Nordsieck Melba Phillips Hartland Snyder George Volkoff |

| Signature | |

| Notes | |

|

Brother of physicist Frank Oppenheimer

|

|

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (born April 22, 1904 – died February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist. This means he studied the ideas and math behind how the universe works. He was also a physics professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

Oppenheimer led the Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. This lab was part of the Manhattan Project, a secret effort to build the first nuclear weapons. Because of his key role, many call him the "father of the atomic bomb." These bombs were later used in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The very first atomic bomb was tested on July 16, 1945. This was called the Trinity test in New Mexico. Oppenheimer later shared his thoughts about that moment: "We knew the world would not be the same." He also remembered a line from a Hindu holy book, the Bhagavad-Gita: "I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

After the war, Oppenheimer became a top advisor for the United States Atomic Energy Commission. He pushed for countries to control nuclear power together. He wanted to stop a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union. However, his strong opinions upset some politicians. In 1954, he lost his security clearance, which limited his political power. Even so, he kept teaching and working in physics. Nine years later, President John F. Kennedy honored him with the Enrico Fermi Award. This award helped restore his public image.

Oppenheimer made many important discoveries in physics. He worked on how molecules move and how electrons and positrons behave. He also helped explain nuclear fusion and predicted quantum tunneling. With his students, he contributed to understanding neutron stars and black holes. He also worked on quantum mechanics and cosmic rays. He is remembered as a key figure in American theoretical physics. After the war, he became the director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Oppenheimer was born in New York City on April 22, 1904. His father, Julius Oppenheimer, was a rich textile importer from Germany. His mother, Ella Friedman, was a painter. His father came to America with nothing and built a successful business. The Oppenheimers were a Jewish family, but they did not strictly follow religious traditions.

In 1912, his family moved to a large apartment in Manhattan. They owned a valuable art collection, including paintings by famous artists like Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh. Robert had a younger brother, Frank Oppenheimer, who also became a physicist.

Education and Early Career

Oppenheimer was a very smart student with many interests. He loved English and French literature, and especially mineralogy, the study of minerals. He skipped several grades in school. In his last year, he became very interested in chemistry.

He started Harvard College at age 18. This was a year later than planned because he got sick during a family trip to Europe. To help him get better, his English teacher took him to New Mexico. There, Oppenheimer discovered a love for horseback riding and the American Southwest.

At Harvard, he studied chemistry. However, Harvard also required science students to learn history, literature, and philosophy or math. He took many courses each term and joined the Phi Beta Kappa honor society. He was so good at physics that he was allowed to take advanced classes right away. He finished his degree in just three years.

In 1926, Oppenheimer went to the University of Göttingen in Germany. This was a top place for theoretical physics. He was very eager to discuss ideas, sometimes talking too much in class. Other students even signed a paper asking his professor, Max Born, to make him quieter. This worked without anyone saying a word.

He earned his Doctor of Philosophy degree in March 1927, when he was 23. He published many important papers on quantum mechanics while at Göttingen.

When he returned to the United States, Oppenheimer became a professor at the University of California, Berkeley. Before starting there, he spent some time recovering from an illness at a ranch in New Mexico. He loved this ranch so much he bought it and called it Perro Caliente, which means "hot dog" in Spanish. He often said that "physics and desert country" were his "two great loves."

At Berkeley, he became a popular teacher and mentor. He helped many young physicists. His students and colleagues found him fascinating. He was known for understanding all parts of physics and for his wide range of interests.

He worked closely with Nobel Prize winner Ernest O. Lawrence, who developed the cyclotron. Oppenheimer helped them understand the information their machines produced. In 1936, he became a full professor at Berkeley.

Important Scientific Work

Oppenheimer did important research in many areas of physics. This included theoretical astronomy (how stars and galaxies work), nuclear physics (the study of atomic nuclei), and quantum field theory (how particles interact). He also studied the math of special relativity and quantum mechanics.

His work helped predict many things discovered later, like the neutron and neutron stars. He also contributed to understanding cosmic rays and quantum tunneling. With his student, Melba Phillips, he developed the Oppenheimer–Phillips process. This theory explains how certain nuclear reactions happen and is still used today.

In the late 1930s, Oppenheimer became interested in astrophysics, the study of stars and space. He wrote papers about white dwarfs and neutron stars. He and his student, Hartland Snyder, also predicted the existence of what we now call black holes in 1939. These papers are among his most famous and helped restart astrophysics research in the U.S. in the 1950s.

Oppenheimer's scientific papers were known for being complex. He liked to use advanced math to explain physics ideas. Sometimes, he made small math errors because he worked so quickly. His student Snyder said, "His physics was good, but his arithmetic awful."

Oppenheimer had many interests outside of science. In 1933, he learned Sanskrit, an ancient Indian language. He read the Bhagavad Gita, a Hindu holy book, in its original language. He later said it was one of the books that most shaped his life philosophy.

Some physicists believe that if Oppenheimer had lived long enough to see his predictions about gravitational collapse, neutron stars, and black holes proven by experiments, he might have won a Nobel Prize. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in physics three times but never won.

Private Life and Political Views

In the 1920s, Oppenheimer was not very aware of world events. He said he didn't read newspapers or listen to the radio. He only learned about the Wall Street Crash of 1929 six months after it happened. He also said he didn't vote until the 1936 United States presidential election.

However, from 1934 on, he became more interested in politics. He started donating money to help German physicists escape Nazi Germany. When his father died in 1937, Oppenheimer left his inheritance to the University of California for student scholarships. Like many smart young people in the 1930s, he supported social changes that some later called communist ideas.

The Manhattan Project

Leading Los Alamos

On October 9, 1941, before the U.S. entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved a secret project to build an atomic bomb. In May 1942, Oppenheimer was asked to lead the work on calculations for fast neutrons, which are key to an atomic bomb. He was given the title "Coordinator of Rapid Rupture."

He organized a summer school at Berkeley to discuss bomb theory. Scientists from Europe and his own students worked hard to figure out what needed to be done to create the bomb.

In June 1942, the U.S. Army started the Manhattan Project. General Leslie Groves was chosen to lead it. Groves then picked Oppenheimer to head the secret weapons laboratory. Many were surprised by this choice because Oppenheimer had left-leaning political views and no experience leading huge projects.

Groves was impressed by Oppenheimer's deep understanding of how to design and build an atomic bomb. He also saw that Oppenheimer had a strong drive to succeed. Oppenheimer and Groves decided they needed a secret lab in a remote place for security.

Oppenheimer suggested a flat area near Santa Fe, New Mexico, close to his ranch. This site was home to a boys' school called the Los Alamos Ranch School. The Los Alamos Laboratory was built there, using some of the school's buildings. Oppenheimer gathered a group of the best physicists of the time, calling them the "luminaries."

Los Alamos quickly grew from a few hundred people in 1943 to over 6,000 in 1945. Oppenheimer learned how to manage such a large project. He was known for understanding all the scientific details and for helping scientists and military staff work together. He was a symbol of their efforts to his fellow scientists.

Physicist Victor Weisskopf said Oppenheimer was always present and involved. He didn't just direct from an office. He was there in the lab, discussing new ideas and measurements. This created a unique feeling of excitement and challenge.

In 1943, scientists worked on a plutonium bomb design called "Thin Man." But they found a problem: the plutonium from reactors wasn't right for this design. In July 1944, Oppenheimer decided to switch to a different design called an "implosion-type" weapon.

He focused efforts on the simpler uranium bomb, which became known as Little Boy. The more complex implosion device, called the "Christy gadget," was finalized in February 1945.

In May 1945, a committee was formed to advise on how to use nuclear energy. The scientists shared their thoughts on the bomb's effects and its military and political impact. They even discussed whether to tell the Soviet Union about the weapon before using it against Japan.

The Trinity Test

The hard work of the Los Alamos scientists led to the first artificial nuclear explosion. This happened near Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945. Oppenheimer named the test site "Trinity."

Oppenheimer later said that when he saw the explosion, he thought of a verse from the Bhagavad Gita: "If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one..." He also recalled the famous verse: "I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

His brother said Oppenheimer simply exclaimed, "It worked." General Thomas Farrell, who was with Oppenheimer, said Oppenheimer was very tense. When the explosion happened, his face relaxed with huge relief. Physicist Isidor Rabi remembered Oppenheimer's proud walk after the test, like a hero.

At Los Alamos on August 6 (the day of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima), Oppenheimer was cheered like a champion. He regretted the bomb wasn't ready to use against Nazi Germany. However, he and many scientists were upset about the bombing of Nagasaki, feeling it wasn't militarily needed.

He went to Washington on August 17 to tell Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson he was horrified and wanted nuclear weapons banned. In October 1945, he met President Harry S Truman. The meeting went poorly after Oppenheimer said he felt he had "blood on my hands." Truman was angry and ended the meeting. For his work at Los Alamos, Oppenheimer received the Medal for Merit in 1946.

Postwar Activities

After the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Manhattan Project became public. Oppenheimer became a national spokesperson for science. His face appeared on the covers of Life and Time. Nuclear physics became very important as governments realized the power of nuclear weapons.

Like many scientists, Oppenheimer believed that safety from atomic bombs would only come if a global group, like the United Nations, controlled nuclear weapons. He wanted a plan to stop a nuclear arms race.

Atomic Energy Commission

Oppenheimer helped shape a report that suggested creating an international Atomic Development Authority. This group would own all nuclear materials and production sites. It would also manage atomic power plants for peaceful energy.

Bernard Baruch turned this report into a proposal for the United Nations, called the Baruch Plan of 1946. This plan included inspecting the Soviet Union's uranium. The Soviets rejected it, seeing it as a way for the U.S. to keep its nuclear lead. Oppenheimer then realized that an arms race was likely.

In 1947, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was created to manage nuclear research and weapons. Oppenheimer became the Chairman of its General Advisory Committee (GAC). He advised on funding, lab building, and international policy.

As GAC Chairman, Oppenheimer strongly supported international arms control and funding for basic science. He tried to guide policy away from a fast arms race. When the government considered building a hydrogen bomb (a more powerful nuclear weapon), Oppenheimer at first advised against it. He worried it would cause millions of deaths.

However, President Truman decided to go ahead with the hydrogen bomb program after the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb in 1949. Oppenheimer and other GAC members who opposed the project felt ignored. They stayed on the committee, even though their views were well known.

In 1951, Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam developed a new design for the hydrogen bomb. This design seemed possible to build. Oppenheimer then changed his mind about developing the weapon. He said the new design was "technically so sweet" that the issues became about military, political, and human problems, not just technical ones.

Security Hearing

The FBI had been watching Oppenheimer since before the war because of his past political views. His home and office were bugged, and his phone was tapped. The FBI gave information about his past connections to his political opponents.

During a hearing, Oppenheimer spoke about the left-wing actions of many of his science friends. If he hadn't lost his clearance, some might have seen him as someone who "named names" to save himself. Instead, most scientists saw Oppenheimer as a victim of unfair attacks.

In 2009, based on KGB archives, it was confirmed that Oppenheimer never spied for the Soviet Union. The KGB tried to recruit him many times but never succeeded. Oppenheimer did not betray the United States.

Final Years and Legacy

Starting in 1954, Oppenheimer spent several months each year on the island of Saint John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. In 1957, he bought land there and built a simple home on the beach. He enjoyed sailing with his daughter Toni and wife Kitty.

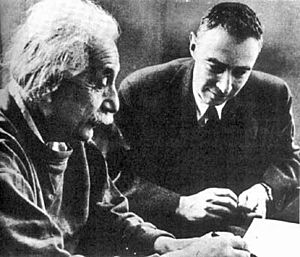

Oppenheimer became more and more worried about the dangers that scientific discoveries could pose to humanity. He joined Albert Einstein and other scientists to create the World Academy of Art and Science.

In his speeches and writings, Oppenheimer often talked about how hard it was to manage powerful knowledge. He worried that political concerns were limiting the freedom of science to share ideas. He published books like Science and the Common Understanding and The Open Mind, which were collections of his lectures on nuclear weapons and society.

Even without political power, Oppenheimer continued to teach, write, and work on physics. He traveled to Europe and Japan, giving talks about science history and its role in society. In 1957, France honored him with the Legion of Honor. In 1962, he became a Foreign Member of the Royal Society in Britain.

Many of Oppenheimer's friends gained power in government. President John F. Kennedy awarded Oppenheimer the Enrico Fermi Award in 1963. This was a way to restore his good name. After Kennedy's death, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented the award. Oppenheimer told Johnson, "I think it is just possible, Mr. President, that it has taken some charity and some courage for you to make this award today."

Oppenheimer was diagnosed with throat cancer in late 1965. He died at his home in Princeton, New Jersey, on February 18, 1967, at age 62. A memorial service was held at Princeton University. Oppenheimer was cremated, and his wife scattered his ashes into the sea near their beach house.

As a scientist, Oppenheimer is remembered as a brilliant researcher and inspiring teacher. He is seen as a founder of modern theoretical physics in the United States. Because his interests changed often, he didn't always finish his work on one topic enough to win a Nobel Prize. However, his work on black holes might have earned him the prize if he had lived longer. An asteroid, 67085 Oppenheimer, and a lunar crater, Oppenheimer, are named after him.

As an advisor, Oppenheimer played a key role in how science and the military worked together. During World War II, scientists became very involved in military research. They helped create important tools like radar and the proximity fuse.

Two days before the Trinity test, Oppenheimer shared his hopes and fears with a quote from the Bhagavad Gita:

In battle, in the forest, at the precipice in the mountains - On the dark great sea, in the midst of javelins and arrows - In sleep, in confusion, in the depths of shame - The good deeds a man has done before defend him

Images for kids

-

Oppenheimer's former colleague, physicist Edward Teller, testified at Oppenheimer's security hearing in 1954.

-

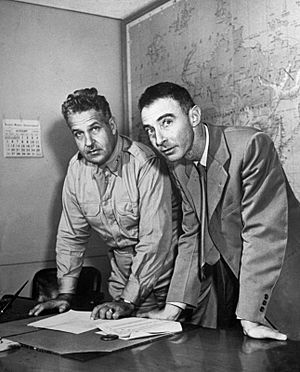

Oppenheimer and Leslie Groves in September 1945 at the remains of the Trinity test in New Mexico.

See also

In Spanish: Robert Oppenheimer para niños

In Spanish: Robert Oppenheimer para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |