Henry L. Stimson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry L. Stimson

|

|

|---|---|

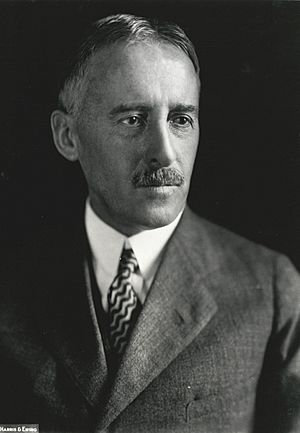

Stimson, c. 1944

|

|

| 45th & 54th United States Secretary of War | |

| In office July 10, 1940 – September 21, 1945 |

|

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt Harry S. Truman |

| Deputy | Robert P. Patterson John J. McCloy |

| Preceded by | Harry H. Woodring |

| Succeeded by | Robert P. Patterson |

| In office May 22, 1911 – March 4, 1913 |

|

| President | William Howard Taft |

| Deputy | Robert Shaw Oliver |

| Preceded by | Jacob M. Dickinson |

| Succeeded by | Lindley Miller Garrison |

| 46th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 28, 1929 – March 4, 1933 |

|

| President | Herbert Hoover |

| Deputy | Joseph P. Cotton William Castle |

| Preceded by | Frank B. Kellogg |

| Succeeded by | Cordell Hull |

| Governor-General of the Philippines | |

| In office December 27, 1927 – February 23, 1929 |

|

| President | Calvin Coolidge |

| Deputy | Eugene Allen Gilmore |

| Preceded by | Leonard Wood |

| Succeeded by | Eugene Allen Gilmore (Acting) |

| United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York | |

| In office January 1906 – April 8, 1909 |

|

| President | Theodore Roosevelt William Howard Taft |

| Preceded by | Henry Lawrence Burnett |

| Succeeded by | Henry Wise |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Henry Lewis Stimson

September 21, 1867 Manhattan, New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 20, 1950 (aged 83) West Hills, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Mabel Wellington White |

| Parent | Lewis Stimson |

| Education | Phillips Academy Andover Yale University (BA) Harvard University (LLB) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

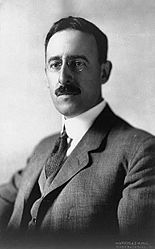

Henry Lewis Stimson (September 21, 1867 – October 20, 1950) was an important American statesman and lawyer. He was a member of the Republican Party. Throughout his long career, he became a key figure in U.S. foreign policy. He worked for both Republican and Democratic presidents.

He served as Secretary of War twice. First, from 1911 to 1913 under President William Howard Taft. Then again from 1940 to 1945 under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman. During his second term, he helped lead America's military efforts in World War II. He was also Secretary of State from 1929 to 1933 under President Herbert Hoover.

Stimson was the son of a surgeon. After studying law, he became a lawyer in Wall Street. President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him as a United States Attorney. In this role, he worked on cases against large companies that tried to unfairly control markets. He also served as Governor-General of the Philippines from 1927 to 1929.

As Secretary of State, Stimson worked to prevent a global naval arms race. He helped create the London Naval Treaty. He also spoke out against Japan's invasion of Manchuria. This led to the Stimson Doctrine, which meant the U.S. would not recognize land changes made by force. When World War II began in Europe, President Roosevelt asked Stimson to return as Secretary of War. He worked closely with Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall. Together, they managed to raise and train 13 million soldiers and airmen. He also oversaw the Manhattan Project, which developed the first atomic bombs. He supported using these bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

After the war, Stimson strongly opposed the Morgenthau Plan. This plan would have turned Germany into a farming country. He also insisted that Nazi war criminals should face trials. This led to the famous Nuremberg trials. Stimson retired in September 1945 and passed away in 1950.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Henry Lewis Stimson was born in Manhattan, New York City. His father, Lewis Atterbury Stimson, was a famous surgeon. When Henry was nine, his mother passed away. He was then sent to a boarding school.

He spent his summers with his grandmother, Candace Wheeler, in the Catskills. He loved being outdoors and became a keen sportsman.

He went to Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. This school sparked his interest in religion. He later gave his property in Washington, D.C. to the school. He was also a lifetime member of Theodore Roosevelt's Boone and Crockett Club. This was North America's first wildlife conservation group.

Stimson then attended Yale College. He joined a secret society called Skull and Bones. This group helped him make many important connections. He graduated in 1888 and then went to Harvard Law School, graduating in 1890. In 1891, he joined a well-known law firm. By 1893, he became a partner. Elihu Root, who would later be Secretary of War and Secretary of State, was a big influence on Stimson.

In July 1893, Stimson married Mabel Wellington White. She was related to Roger Sherman, one of the Founding Fathers. They did not have any children. The couple went on their honeymoon to Kyoto, Japan. This trip was important later when Stimson decided not to drop an atomic bomb on that city.

In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt made Stimson a U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York. He became known for successfully prosecuting antitrust cases. These cases were against businesses that tried to stop fair competition.

Stimson ran for Governor of New York in 1910 but lost. He also joined the Council on Foreign Relations when it started. This group focuses on international issues.

Secretary of War (1911–1913)

In 1911, President William Howard Taft chose Stimson to be Secretary of War. In this role, Stimson continued to improve the United States Army. These changes made the army more efficient. This was very helpful before its large growth in World War I. In 1913, Stimson left his position when President Woodrow Wilson took office.

World War I Service

When World War I started in 1914, Stimson strongly supported Britain and France. However, he also believed the U.S. should remain neutral at first. He pushed for the U.S. to build a strong army. He was active in a movement that trained potential officers.

After the U.S. entered the war in 1917, Stimson joined the regular U.S. Army. He served as an artillery officer in France. By August 1918, he reached the rank of colonel. He continued his military service after the war. He became a brigadier general in 1922.

Work in Nicaragua and the Philippines

In 1927, President Calvin Coolidge sent Stimson to Nicaragua. His job was to help end the civil war there. Stimson believed that Nicaraguans were not ready for full independence.

He held a similar view about the Philippines. He was appointed Governor-General of the Philippines from 1927 to 1929. In this role, he also opposed giving the Philippines full independence.

Secretary of State

Stimson returned to the President's cabinet in 1929. President Herbert Hoover appointed him as US Secretary of State. He served in this role until 1933.

Soon after becoming Secretary of State, Stimson closed the "Cipher Bureau" in 1929. This was a U.S. group that secretly read other countries' messages. Stimson believed that reading diplomatic messages was wrong. He famously said, "Gentlemen do not read each other's mail."

In 1930 and 1931, Stimson led the U.S. team at the London Naval Conference of 1930. This meeting aimed to limit the size of navies. The next year, he led the U.S. team at a global disarmament conference in Geneva.

In 1932, the United States announced the "Stimson Doctrine." This was in response to Japan's invasion of Manchuria. The doctrine stated that the U.S. would not recognize any changes made by force. After leaving government, Stimson continued to speak out against Japan's actions.

Secretary of War (1940–1945)

When World War II began, President Roosevelt asked Stimson to be Secretary of War again. This happened in July 1940. Roosevelt chose Stimson, a Republican, to show that both parties supported preparing for war.

For 17 months before the attack on Pearl Harbor, Stimson worked closely with Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall. They prepared America for war. They built up the Army and Air Force. They also organized housing and training for soldiers. They oversaw the creation and delivery of weapons and supplies.

Stimson was 73 when he became War Secretary. Many wondered if he was too old for such a big job. But he worked with great energy. He proved his critics wrong.

Japanese American Internment

Stimson first opposed moving Japanese Americans away from the West Coast. But he eventually agreed with military advisors who wanted them moved. He helped get President Roosevelt's approval for this program.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, some government officials argued against it. However, Army leaders pushed for immediate relocation. By February 1942, Stimson was convinced.

On February 11, Stimson spoke with Roosevelt. Roosevelt gave him permission to do what he thought was best. Two days later, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. This order allowed military zones where certain people could be excluded.

Stimson also wanted to exclude Japanese people from Hawaii. But Japanese Hawaiians were the largest ethnic group there. They were vital to the island's workforce. So, moving them all was not possible.

Stimson believed it was hard to know who was loyal among Japanese Americans. He supported the army's plan to hold them. But he was unsure if it was legal. He worried it would harm the U.S. Constitution.

Stimson allowed Japanese Americans to leave the camps in May 1944. But he delayed their return to the West Coast. This was to avoid problems during Roosevelt's election campaign in November.

General Patton Incident

On November 21, 1943, news spread about General George S. Patton. He had slapped a soldier suffering from stress in Sicily. Many in Congress wanted Patton removed from command.

However, General Dwight Eisenhower believed Patton was essential for the war effort. Stimson agreed. He told the Senate that Patton would stay. He said Patton's strong leadership was needed for the battles ahead.

Morgenthau Plan Opposition

Stimson strongly opposed the Morgenthau Plan. This plan wanted to remove industries from Germany. It also aimed to divide Germany into smaller states. Stimson argued that many European countries depended on German trade. He said it was wrong to turn Germany into a "ghost territory."

He feared that a poor Germany would turn against the Allies. This would make people forget the Nazis' crimes. Stimson made similar arguments to President Harry S. Truman in 1945.

Stimson, a lawyer, insisted on proper trials for war criminals. This was against the wishes of Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Stimson and the War Department created the first ideas for an International Tribunal. This led to the Nuremberg Trials of 1945–1946. These trials greatly influenced international law.

Atomic Bomb Decision

As Secretary of War, Stimson directly oversaw the atomic bomb project. This was known as the Manhattan Project. He worked closely with General Leslie Groves, who led the project. Both Roosevelt and Truman listened to Stimson's advice on the bomb. Stimson even overruled military officers when they disagreed with him.

For example, military planners wanted to target Kyoto for a nuclear attack. But Stimson remembered his honeymoon there. He overruled his generals, saying it was an important cultural center. So, Hiroshima was chosen instead.

Stimson made sure the project had enough money and approval from Congress. He also controlled all plans for using the bomb. He pushed for the "Little Boy" bomb to be dropped on Hiroshima as soon as possible. The goal was to force Japan to surrender.

Stimson later thought that if the U.S. had promised to keep Japan's emperor, Japan might have surrendered. This could have prevented the use of atomic bombs. Historians still debate if Japan would have surrendered without the bombs.

After a journalist wrote about the Hiroshima bombing, Stimson published his own article. It was called "The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb." He argued that the bombings saved Japanese lives. He also said that showing the bomb's power first was not practical. He claimed an invasion would cause over a million American casualties. This article became the first official explanation for the bombings.

Stimson's Vision for the Atomic Age

Stimson looked beyond the end of the war. He was one of the few leaders to think about the meaning of the Atomic Age. He saw it as a new era for humanity. He believed the atomic bomb's power went beyond military concerns. It would affect diplomacy, world affairs, and science.

Stimson stated that this "most terrible weapon" offered a chance for world peace. He thought the bomb's destructive power would show that wars could no longer be beneficial. He believed it might stop the use of destruction to solve conflicts.

To achieve this, Stimson wanted to work with the Soviet Union. He also supported international control of atomic technology. He even considered giving atomic weapons to the United Nations. He was opposed by others in the Truman administration.

In 1931, Stimson had created the Stimson Doctrine. It said the U.S. would not recognize land taken by force. He believed the atomic bomb could now punish Japan's actions. This would warn other countries not to invade their neighbors.

For Stimson, the question was not whether to use the weapon. It was about ending a terrible war. It was also about the chance for true peace among nations. Stimson's decision involved the future of humanity. He made it clear that atomic weapons should never be used to kill people again.

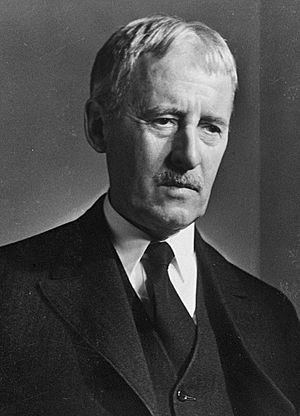

Later Life and Legacy

Stimson announced his retirement on September 21, 1945. After leaving office, he wrote his memoirs. The book, On Active Service in Peace and War, was published in 1948. Historians often use it and his detailed daily diaries.

In November 1945, Stimson had a heart attack. He recovered but had trouble speaking. In the summer of 1950, he broke his leg and used a wheelchair. On October 20, 1950, he passed away from complications from a second heart attack. He was 83 years old. Stimson is buried in Cold Spring Harbor. He was the last living member of President Taft's cabinet.

Anecdote

A writer named Theodore H. White noted that Stimson had known more presidents than any other American of his time. Before Stimson died, a friend asked him who was "the best" president he had known. Stimson thought about it. He said if "best" meant most efficient, it was William Howard Taft. If "greatest" meant the best, it was "Roosevelt." But Stimson couldn't decide between Theodore or Franklin. He said both understood and enjoyed using power.

Awards

- Distinguished Service Medal (U.S. Army)

- World War I Victory Medal

- American Legion Distinguished Service Medal

Legacy

Mount Stimson in Montana's Glacier National Park is named after him. Stimson hiked and helped survey the area in the 1890s. He later supported creating the park.

The Henry L. Stimson Center is a research group in Washington, DC. It promotes Stimson's "practical, non-partisan approach" to international relations.

A ballistic missile submarine, the USS Henry L. Stimson (SSBN-655), was named after him in 1966.

Stimson's name is also on the Henry L. Stimson Middle School in Huntington Station, Long Island. A building at Stony Brook University and a dorm at Phillips Academy are also named for him.

The New York City Bar Association awards the Henry L. Stimson Medal. This medal honors outstanding Assistant U.S. Attorneys in New York. Stimson was president of this association from 1937 to 1939.

See also

In Spanish: Henry L. Stimson para niños

In Spanish: Henry L. Stimson para niños

- List of U.S. political appointments that crossed party lines

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |