Nuremberg trials facts for kids

The Nuremberg Trials were a series of important trials held by the Allied countries after World War II. These trials were against leaders of Nazi Germany. They were accused of planning and carrying out invasions of other countries. They also committed terrible crimes against many people, especially Jewish people, during the war.

Between 1933 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded many countries in Europe. Millions of people died, including 27 million in the Soviet Union alone. The Allies (France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States) decided to hold a special court. This court was called the International Military Tribunal (IMT). It took place in Nuremberg, Germany.

The trials happened from November 20, 1945, to October 1, 1946. The IMT tried 22 of the most important surviving Nazi leaders. Six German organizations were also put on trial. The goal was not just to punish them. It was also to show clear proof of their crimes. It was also meant to teach Germans about their history and show that the old Nazi leaders were wrong.

The IMT decided that planning and starting an aggressive war was "the supreme international crime." This meant it was the worst crime because it led to all other terrible acts. Most defendants were also charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity. The systematic murder of millions of Jewish people in the Holocaust was a very important part of the trials. Later, the United States held 12 more trials for other Nazi officials. These trials focused more on the Holocaust. The Nuremberg Trials were new because they held individuals responsible for breaking international laws. This is seen as the start of international criminal law.

Quick facts for kids International Military Tribunal |

|

|---|---|

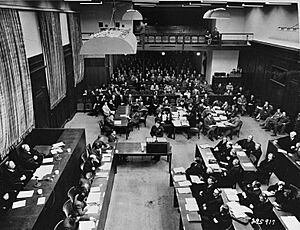

Judges' bench during the tribunal at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Allied-occupied Germany

|

|

| Indictment | Conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes, crimes against humanity |

| Started | 20 November 1945 |

| Decided | 1 October 1946 |

| Defendant | 24 (see list) |

| Case history | |

| Related action(s) | Subsequent Nuremberg trials International Military Tribunal for the Far East |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting |

|

Contents

Why the Trials Were Needed

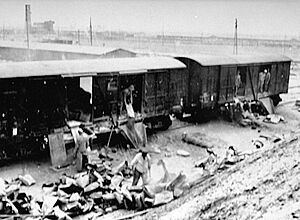

Between 1939 and 1945, Nazi Germany invaded many European countries. These included Poland, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and the Soviet Union. German attacks were very brutal. In the Soviet Union alone, 27 million people died. Most of them were civilians. The trials were held because the Nazi crimes were so extreme. This included the planned murder of millions of Jewish people, known as The Holocaust.

In 1942, leaders from German-occupied countries wanted an international court. They wanted to try Germans for crimes committed in their lands. The United States and United Kingdom were unsure at first. They remembered that trials after World War I had not worked well.

The Soviet Union, UK, and US warned Nazi leaders in 1943. They said they would be hunted down and brought to justice. They agreed that high-ranking Nazis who committed crimes in many countries would be tried together. Others would be tried where their crimes happened.

A Soviet lawyer, Aron Trainin, developed the idea of "crimes against peace." This meant starting an aggressive war. This idea became very important at Nuremberg. The Soviet Union pushed hard to try German leaders for aggression and war crimes. They wanted a trial to show the Nazis' guilt. The United States wanted a fair trial to help Germany change. They also wanted to show that their justice system was better. The British government still thought it might be better to just execute Nazi leaders. They worried about making new laws after the crimes happened.

At a meeting in February 1945, they still hadn't decided how to punish the Nazis. On May 2, US President Harry S. Truman announced an international military court. On May 8, Germany surrendered, ending the war in Europe.

Setting Up the Court

The Nuremberg Charter

From June to August 1945, representatives from France, the Soviet Union, the UK, and the US met in London. They discussed how the trial would work. It wasn't even clear if a trial would happen at all.

They decided the crimes to be tried would be: crimes against peace, crimes against humanity, and war crimes. Starting an aggressive war was not a crime in international law before this. But US negotiator Robert H. Jackson insisted it must be included. He said the US would leave if it wasn't.

War crimes were already against international law. But these laws didn't cover a government's crimes against its own people. Lawyers wanted a way to try crimes against German citizens, like Jewish people. The idea of "crimes against humanity" was created. This included "murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population." The court could only try crimes against humanity if they were part of an aggressive war.

The charter changed international law. It said individuals, not just countries, could be held responsible for breaking these laws. It also said defendants could not claim they were just following orders. The trial followed a modified English legal system. The trial was held at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg. This city was chosen because it was where the Nazis held their big rallies. The Palace of Justice was mostly undamaged and had a prison attached. On August 8, the Nuremberg Charter was signed.

Judges and Lawyers

By early 1946, about a thousand people from the four countries worked in Nuremberg. They were lawyers, researchers, psychologists, and translators. Each country chose a team of prosecutors and two judges.

Robert H. Jackson was the chief US prosecutor. He was a good speaker. The US team believed Nazism was a bad path for Germany. They wanted the trial to help Germany change. The British chief prosecutor was Hartley Shawcross. The main British judge, Sir Geoffrey Lawrence, was the tribunal's president. But the US judge, Francis Biddle, had more power.

The French prosecutor was François de Menthon, later replaced by Auguste Champetier de Ribes. The French judges were Henri Donnedieu de Vabres and Robert Falco. The Soviet chief prosecutor was Roman Rudenko. He was chosen for his speaking skills. Soviet judges and prosecutors had to get approval from Moscow for big decisions. This sometimes caused delays.

Requests from Jewish and Polish groups to have a bigger role were denied. But Poland did send evidence and an indictment. This helped bring attention to crimes against Polish people.

The Charges

Each country's team helped write the charges. The British worked on aggressive war. France covered crimes on the Western Front. The Soviet Union covered crimes on the Eastern Front. The US team outlined the overall Nazi plan and crimes of Nazi groups.

The charge of "conspiracy" (a secret plan to do something illegal) was important. It linked many different crimes and defendants. It allowed them to charge top Nazi leaders and even bureaucrats who didn't directly kill anyone. This charge also helped include crimes committed before World War II began. It was used against propagandists and business leaders. The US pushed for this charge, but France was less keen.

Translating all the charges and evidence into English, French, Russian, and German was a huge task. The Soviet Union wanted changes to the charges about crimes against peace. This was because of their pact with Germany at the start of the war. The charges were prepared quickly. This led to some repetition and unclear language.

The Defendants

Some of the most famous Nazis, like Adolf Hitler, had died by suicide. So, they couldn't be tried. The prosecutors wanted to try leaders from German politics, business, and military. Most defendants had surrendered to the US or UK.

The defendants were mostly unrepentant. They included former government ministers like Joachim von Ribbentrop (foreign minister) and Wilhelm Frick (interior minister). Business leaders like Hjalmar Schacht and Albert Speer were also on trial. Military leaders included Hermann Göring, Wilhelm Keitel, and Karl Dönitz. Others were propagandists like Julius Streicher, and leaders of Nazi groups like Baldur von Schirach (Hitler Youth). Many observers found the defendants unimpressive.

Of the 24 men charged, Martin Bormann was tried without being present, as the Allies didn't know he was dead. Gustav Krupp was too sick for trial. Robert Ley died by suicide before the trial started. Former Nazis were allowed to be lawyers for the defendants. The defense lawyers argued the court had no right to try their clients. But the court rejected this.

Six Nazi organizations were also put on trial. These included the Nazi Party Leadership, the Gestapo, and the SS. The goal was to declare these groups criminal. This would make it easier to try their members later.

The Evidence

All the countries worked hard to gather evidence. The American and British lawyers mostly used documents and written statements. They used less testimony from survivors. This made their case more believable. The US used reports from its intelligence agency. The French used documents they got from Jewish organizations.

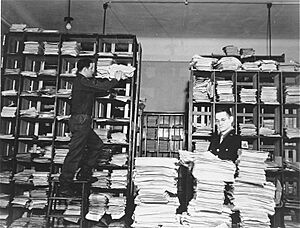

The prosecution called 37 witnesses, and the defense called 83. The prosecution looked at 110,000 captured German documents. They used 4,600 of them as evidence. They also used 30 kilometers of film and 25,000 photos.

The court allowed any evidence that seemed useful. Photos, charts, maps, and films were very important. They helped make the terrible crimes seem real. At first, the US presented many documents. The judges then said all evidence had to be read aloud. This made the trial very slow.

The Trial in Action

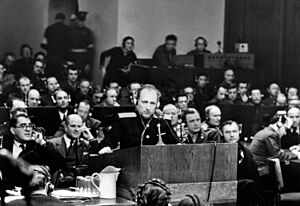

The International Military Tribunal began on November 20, 1945. All defendants said they were not guilty. Prosecutor Jackson said the trial was not just about convicting the defendants. It was also to show clear proof of Nazi crimes. It aimed to establish that individuals could be held responsible for international crimes. It also aimed to teach Germans about their history.

Jackson said the US did not want to blame all Germans. But the defense lawyers often argued that the prosecution was trying to make all Germans feel guilty. The evidence about the Holocaust convinced some people that Germans must have known what was happening.

American and British Cases

On November 21, Jackson gave his opening speech. He said it was amazing that the defeated Nazis got a trial. He focused on aggressive war, calling it the cause of all other crimes. His speech was well-received.

The American case focused on the Nazi plan before the war. On November 29, the prosecution showed a film called Nazi Concentration and Prison Camps. It showed footage from the liberation of Nazi concentration camps. This film shocked everyone, including the defendants and judges. The judges stopped the trial for a break. The American prosecutors also called Otto Ohlendorf, an SS commander. He testified about killing 80,000 people.

The British case also covered crimes against peace. Shawcross gave his opening speech on December 4. He argued that the charges of aggression were not new. He said they were based on older international agreements. The British showed how Germany broke many treaties. In January, both the British and Americans presented evidence against individual defendants.

French Case

From January 17 to February 7, 1946, France presented its charges. The French lawyers focused on Germany's history. They argued that Nazi ideas were the reason for the crimes. They emphasized that many Germans were involved. They focused on forced labor, stealing property, and massacres.

French prosecutor Edgar Faure talked about "Germanization." This was Germany's plan to make other areas German. He said this was a crime against humanity. The French used police reports and victim testimonies. Eleven witnesses were called, including a survivor of Auschwitz. The court accepted most of France's war crimes charges.

Soviet Case

On February 8, the Soviet prosecution began. Rudenko's speech covered all four charges. He highlighted the many crimes committed by German occupiers. The Soviets brought Friedrich Paulus, a German field marshal captured after the Battle of Stalingrad, as a witness. Paulus blamed Keitel, Jodl, and Göring for the war.

Soviet prosecutors showed gruesome details of German crimes. This included the deaths of 3 million Soviet prisoners of war. They also showed the deaths of hundreds of thousands in Leningrad. They talked about the systematic murder of Jewish people in Eastern Europe. They also presented evidence of the Lidice massacre in Czechoslovakia. They showed how Germans destroyed villages and murdered people. They emphasized the racist policies, like forced labor and stealing cultural items.

The Soviet Union also made three films for the trial. These films showed German destruction and atrocities in the USSR. One film showed the liberation of Majdanek concentration camp and Auschwitz. It was very disturbing. Soviet witnesses included survivors of German crimes. These included people who lived through the siege of Leningrad and Holocaust survivors. The Soviet case was well-received. It showed strong evidence of the suffering of the Soviet people.

The Defense

From March to July 1946, the defense presented its arguments. It was clear that the prosecution had proven its general case. The defense's job was to show the individual guilt of each defendant. None of the defendants denied that the Nazi crimes happened. Some denied being involved or claimed they didn't know about them. A few lawyers said Germans were just following orders from a totalitarian state. They argued this meant Germans weren't personally guilty.

The defendants tried to blame their crimes on Hitler. He was mentioned 1,200 times. They also blamed other dead or absent men like Himmler. Most defendants tried to say they were not important in the Nazi system. But Göring took the opposite approach. He expected to be executed but wanted to be seen as a hero by Germans.

The court did not allow the defense to say the Allies committed the same crimes. The judges rejected arguments that Nazi laws were like laws in other countries. They also rejected comparisons between Nazi camps and Allied detention centers. The judges mostly stopped evidence about Allied wrongdoings from being heard.

Many defense lawyers complained about the trial process. They tried to make the whole trial seem unfair. To calm them, the defendants were allowed to call many witnesses. Some witnesses helped the defendants. But others, like Rudolf Höss (former commandant of Auschwitz), helped the prosecution's case. As the Cold War began, the trial also became a way to criticize the Soviet Union.

Closing Arguments

On August 31, closing arguments were given. During the trial, crimes against humanity, especially against Jewish people, became more important than the aggressive war charge. All closing statements highlighted the Holocaust. French and British prosecutors made this their main charge. All prosecutors except the Americans mentioned "genocide." This word was recently created by a Polish-Jewish lawyer, Raphael Lemkin.

Most defendants disappointed the judges with their lies and denials. Speer seemed to apologize without taking personal blame. On September 2, the court took a break. The judges went to decide the verdict and sentences.

The Verdict

The International Military Tribunal agreed that aggression was the most serious charge. They said starting an aggressive war was "the supreme international crime." This was because it led to all other terrible acts. The judges did not try to define aggression. They also didn't mention that the charges were new laws made after the crimes. The judges knew that both the Allies and Axis had planned aggressive acts. They wrote the verdict carefully to avoid discrediting anyone.

The judges ruled that there was a planned conspiracy to commit crimes against peace. Its goal was to disrupt Europe and create a "Greater Germany." The verdict said the planning of aggression started in 1937. Only eight defendants were found guilty of this conspiracy. All 22 defendants were charged with crimes against peace, and 12 were convicted. The charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity were mostly upheld. Only two defendants charged with these were found not guilty. The judges said crimes against German Jews before 1939 were not under the court's power. This was because no link to aggressive war was proven.

Four organizations were declared criminal: the Nazi Party Leadership, the SS, the Gestapo, and the SD. But some lower ranks and subgroups were excluded. This meant that only individuals who willingly joined and knew the criminal purpose could be held responsible. The SA, the Reich Cabinet, and the German military's General Staff were not declared criminal organizations.

The judges debated the sentences for a long time. Twelve defendants were sentenced to death. These included Göring, Ribbentrop, and Keitel. On October 16, ten were executed. Göring died by suicide the day before. Seven defendants were sent to prison. Three defendants were found not guilty. This surprised observers. For example, Sauckel was sentenced to death, but Speer got a prison sentence. The judges thought Speer could change. The Soviet judge disagreed with all the acquittals. He wanted Hess to be sentenced to death.

Later Trials

At first, another international trial for German business leaders was planned. But it never happened due to disagreements among the Allies. The United States then held 12 more military trials. These took place in the same courtroom in Nuremberg. US forces arrested almost 100,000 Germans as war criminals. Of these, 177 were tried. Many of the worst offenders were not prosecuted due to practical reasons.

Some trials focused on German professionals. The Doctors' trial was about human experiments. The Judges' trial was about the role of judges in Nazi crimes. The Ministries Trial was about government officials. Business leaders were also tried for using forced labor and stealing property. Members of the SS were tried for overseeing concentration camps. The Einsatzgruppen trial was for mobile killing squads. These squads murdered over a million people.

These later trials focused on the crimes of the Holocaust. They heard 1,300 witnesses and used over 30,000 documents. Of 177 defendants, 142 were convicted. Twenty-five were sentenced to death. These trials greatly helped develop international criminal law.

How People Reacted

Many journalists covered the IMT. Over 60,000 visitor tickets were issued. In France, people were angry about some sentences. They thought they were too light. In the UK, it was hard to keep public interest in such a long trial.

Many Germans at the time were focused on finding food and shelter. But most still read news about the trial. In 1946, 78% of Germans thought the trial was fair. But four years later, only 38% thought so. Many Germans later saw the trials as unfair "victor's justice." They felt they were being blamed as a whole.

As the Cold War began, the trials' impact changed. The goal of educating Germans about war crimes failed. This was partly because Germans resisted the idea. Also, the US Army didn't publish the trial records in German. They feared it would hurt the fight against communism.

German churches and politicians wanted war criminals to be pardoned. The Americans agreed to this to make West Germany an ally against communism. Early releases of prisoners began in 1949. By 1951, most sentences were overturned. The last three prisoners were released in 1958. The German public saw these early releases as proof that the trials were not fair. But the IMT defendants needed Soviet permission for release. Speer was not released early. Hess stayed in prison until his death in 1987. By the late 1950s, Germans started to change their minds about the releases. New information about Nazi crimes came out. West German courts also began their own trials.

Lasting Impact

The International Military Tribunal and its charter truly started international criminal law. The trial has received mixed reactions. At first, it was mostly negative, but it has become more positive over time.

One common criticism is that only the defeated Axis powers were tried. Critics point out that the Allies also did things that would be illegal under the Nuremberg rules. These include the German-Soviet pact and the forced movement of millions of Germans. Another debate is about trying people for acts that were not crimes at the time. This is especially true for crimes against peace. But crimes against humanity and holding individuals responsible were less controversial.

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (Tokyo Trial) used many ideas from the IMT. In 1946, the United Nations General Assembly agreed to the principles of the Nuremberg Tribunal. In 1950, the International Law Commission wrote the Nuremberg principles. These were meant to codify international criminal law. But the Cold War stopped them from being adopted until the 1990s. The 1948 Genocide Convention was also limited by Cold War politics.

In the 1990s, international criminal law saw a revival. New international courts were set up for Yugoslavia and Rwanda. These were seen as part of the Nuremberg legacy. A permanent International Criminal Court (ICC) was proposed in 1953 and finally established in 2002.

The trials were the first to use simultaneous interpretation. This led to new ways of translating. The Palace of Justice now has a museum about the trial. The courtroom is a tourist attraction. The IMT is one of the most studied trials in history. Many books, studies, and films have been made about it.

See also

In Spanish: Juicios de Núremberg para niños

In Spanish: Juicios de Núremberg para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |