Raphael Lemkin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

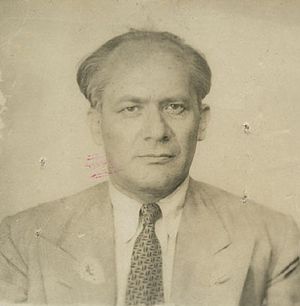

Raphael Lemkin

|

|

|---|---|

| Rafał Lemkin | |

|

|

| Born | 24 June 1900 Bezwodne, Volkovyssky Uyezd, Grodno Governorate, Russian Empire

(now Zelʹva District, Grodno Region, Belarus) |

| Died | 28 August 1959 (aged 59) New York City, U.S.

|

| Nationality | Polish |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Known for |

|

Raphael Lemkin (Polish: Rafał Lemkin; 24 June 1900 – 28 August 1959) was a Polish lawyer. He is famous for creating the word genocide. He also started the idea for the Genocide Convention. This is an international agreement to prevent and punish genocide.

Lemkin became interested in these ideas after learning about the Armenian genocide. He found that no international laws existed to punish the leaders who committed such terrible acts. He created the word genocide in 1943 or 1944. It comes from the Greek word genos (meaning 'family' or 'race') and the Latin word -cide (meaning 'killing').

Contents

Lemkin's Early Life and Education

Growing Up in Poland

Raphael Lemkin was born on 24 June 1900. His birthplace was Bezwodne, a village in what was then the Russian Empire. Today, this area is part of Belarus. He grew up on a large farm with his Polish Jewish family. He was one of three sons. His father was a farmer, and his mother was very smart. She was a painter, spoke many languages, and loved philosophy and books. Lemkin and his brothers were taught at home by their mother.

From a young age, Lemkin was very interested in terrible events in history. He would ask his mother about things like the destruction of Carthage and the persecution of Huguenots. When he was 12, he read a book called Quo Vadis. It described how Nero treated Christians in ancient Rome. These stories made him think about a pattern of violence throughout history. He believed that the suffering he saw in his own time was part of this larger pattern.

World War I and Its Impact

During World War I, fighting happened near Lemkin's family farm. His family had to hide their books and valuables. They took shelter in a nearby forest. Their home was destroyed by bombs. German soldiers took their crops and animals. Sadly, Lemkin's brother Samuel died from illness and lack of food while they were in the forest.

After the war, Lemkin went to a trade school in Białystok. Then he studied languages at Jan Kazimierz University in Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine). He was very good with languages. He could speak nine languages fluently and read fourteen!

A Spark for Justice

It was in Białystok that Lemkin first thought about laws against mass killings. He learned about the Armenian genocide in the Ottoman Empire. Later, he heard about the Simele massacre of Assyrians in Iraq in 1933. These events deeply affected him.

In 1921, a man named Soghomon Tehlirian killed Talaat Pasha in Berlin. Talaat Pasha was a main leader of the Armenian genocide. Lemkin asked his law professor why Talaat Pasha could not be tried in a German court for his crimes. The professor explained that "state sovereignty" meant governments could do what they wanted within their own borders. He used an example: "A farmer owns chickens. He kills them, and that's his business. If you interfere, you are trespassing." Lemkin famously replied, "But the Armenians are not chickens." He realized that a government's right to rule should not include the right to kill millions of innocent people. This idea became central to his life's work.

Lemkin's Career and the Idea of Genocide

Working as a Lawyer in Poland

After his studies, Lemkin worked as a prosecutor and then a private lawyer in Warsaw, Poland. From 1929 to 1934, he was a Public Prosecutor for the Warsaw district court. He also helped write Poland's criminal laws. He taught law at Tachkemoni College in Warsaw.

In 1933, Lemkin spoke at a conference in Madrid. He presented an idea for a new international crime called the Crime of Barbarity. This crime would punish mass killings. Because of his strong views at this conference, he resigned from his government job. He then became a private lawyer in Warsaw.

During World War II

When World War II began in 1939, Lemkin had to flee Poland. He narrowly escaped capture by German and Soviet forces. He traveled through Lithuania and reached Sweden in 1940. In Sweden, he lectured at the University of Stockholm. He started collecting Nazi laws and orders. He wanted to understand how the Nazis were taking control of countries. He saw that their goal was to destroy entire groups of people.

With help, Lemkin was able to move to the United States in 1941. He joined the law faculty at Duke University. He also advised the US government on international law.

Sadly, Lemkin lost 49 family members in the Holocaust. Only his brother Elias, Elias's wife, and their two sons survived. They had been sent to a Soviet labor camp. Lemkin later helped them move to Canada.

In 1944, Lemkin published his most important book, Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. This book analyzed how Nazi Germany ruled the countries it took over. In this book, he officially defined the term genocide. He explained genocide as a crime against international law. This idea was widely accepted. It became one of the legal foundations for the Nuremberg Trials. These trials punished Nazi leaders for their terrible crimes after the war. From 1945 to 1946, Lemkin advised Robert H. Jackson, the chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials.

After the War: The Genocide Convention

A New Law for the World

After World War II, Lemkin stayed in the United States. He taught law at Yale University and later at Rutgers School of Law. He continued his fight for international laws against genocide. He had been working on this since 1933.

Lemkin wrote a draft for a new treaty called the Genocide Convention. He worked hard to convince many countries to support it. With the help of the United States, the idea was presented to the United Nations. On 9 December 1948, the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was officially adopted. This was a huge step!

In 1951, the Convention became international law after 20 countries agreed to it. This was a major success for Lemkin. He believed that genocide was not just about physical killing. It also included psychological acts meant to destroy a group.

Lemkin also worked with governments to make genocide illegal in their own countries. He even recognized the Ukrainian Holodomor (a terrible famine in the 1930s) as a genocide. He wrote about it in his 1953 article "Soviet Genocide in Ukraine."

Later Life and Legacy

In his final years, Lemkin lived simply in New York. He died in 1959 from a heart attack at age 59. Only a few close friends attended his funeral. He was buried in Mount Hebron Cemetery in New York City. He left behind several unfinished books about genocide.

Sadly, the United States, Lemkin's adopted country, did not agree to the Genocide Convention during his lifetime. He felt that his efforts to prevent genocide had failed. He wrote that his work was like "rain... a mixture of the blood and tears of eight million innocent people."

However, Lemkin's work became much more recognized in the 1990s. This was when international courts began to prosecute genocide in places like the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. Today, "genocide" is understood as one of the worst crimes a group can commit.

Recognition and Awards

For his important work, Lemkin received many awards:

- The Grand Cross of the Order of Carlos Manuel de Cespedes from Cuba in 1950.

- The Stephen Wise Award from the American Jewish Congress in 1951.

- The Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1955.

He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize ten times. In 1989, after his death, he received the Four Freedoms Award for the Freedom of Worship.

Lemkin's life has been featured in plays and a documentary film called Watchers of the Sky (2014). An organization called T’ruah gives the Raphael Lemkin Human Rights Award each year to people who work for human rights.

In 2015, Lemkin's article "Soviet Genocide in Ukraine" was banned in Russia. In 2018, a special plaque was unveiled in New York City. It honored Lemkin for recognizing the Holodomor as a genocide.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Raphael Lemkin para niños

In Spanish: Raphael Lemkin para niños

- Crimes against humanity

- War crime

- International criminal law

- Genocide

- Armenian genocide

- Holodomor

- The Holocaust

- Porajmos

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |