Morgenthau Plan facts for kids

The Morgenthau Plan was a suggestion to stop Germany from being able to start another war after World War II. It aimed to do this by getting rid of Germany's weapons factories and destroying other important industries that could help build military power. This included taking apart or destroying all factories and equipment in the Ruhr area.

The plan was first suggested by Henry Morgenthau Jr., who was the United States Secretary of the Treasury. He wrote it down in a paper in 1944 called Suggested Post-Surrender Program for Germany.

Even though the Morgenthau Plan influenced some early ideas for how the Allies would control Germany, it was never fully put into action. The United States' plans for occupying Germany did try to reduce its industrial power. However, these plans had ways to avoid large-scale destruction of mines and factories. From 1947, U.S. policies changed to help Germany become stable and productive again. This led to the Marshall Plan, which helped rebuild Europe.

When the Morgenthau Plan became public in September 1944, the German government quickly used it. They turned it into propaganda to convince Germans to keep fighting hard in the last months of the war.

Contents

- Morgenthau's Ideas for Germany

- Meetings About the Plan

- Roosevelt's Support

- Churchill's First Disagreement

- The Plan is Rejected

- Impact During the War

- Influence on Policy

- JCS 1067 Policy

- Morgenthau's Book

- How the Plan Was Carried Out (or Not)

- Plans for German Industry

- What Historians Think Today

- See also

Morgenthau's Ideas for Germany

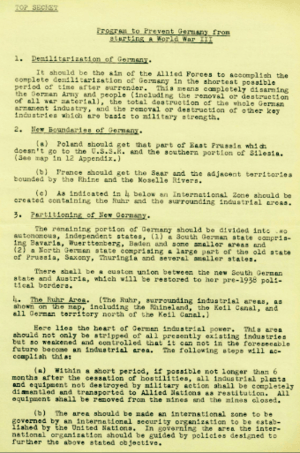

The original paper, written by Henry Morgenthau Jr., is kept at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. It was called "Suggested Post-Surrender Program for Germany."

Here are the main ideas from Morgenthau's plan:

- Stop Germany from having a military: The Allies should completely disarm Germany very quickly after the war. This meant taking away all weapons, destroying all war factories, and getting rid of other key industries that could be used for military strength.

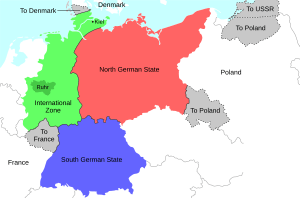

- Divide Germany: Germany should be split into several smaller, independent countries.

- Part of East Prussia and southern Silesia would go to Poland and the Soviet Union.

- France would get the Saar and nearby areas.

- The Ruhr and its industrial areas would become an International zone controlled by other countries.

- The rest of Germany would be divided into two separate states: a South German state and a North German state.

- The South German state would include Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden.

- The North German state would include parts of Prussia, Saxony, and Thuringia.

- Control the Ruhr Area: This area was the heart of Germany's industrial power. The plan said it should be stripped of all existing industries. It should be weakened so it could not become an industrial area again.

- Within six months after the war, all factories and equipment not destroyed by fighting would be taken apart or destroyed. Mines would be wrecked.

- People with special skills or training in this area would be encouraged to move away permanently.

- The area would become an international zone managed by a global security group.

- Reparations and Restitution: Germany would not pay ongoing payments. Instead, it would give up existing resources and territories.

- Property stolen by Germans in occupied lands would be returned.

- German land and industrial property in those areas would be given to invaded countries.

- Factories and equipment from the international zone and the new German states would be removed and given to countries that were damaged by the war.

- Germans would be forced to work outside Germany.

- All German assets (money, property) outside Germany would be taken.

Meetings About the Plan

At a meeting in Quebec City in September 1944, Winston Churchill (from Britain) and Franklin D. Roosevelt (from the U.S.) discussed a plan for Germany. This plan was based on Morgenthau's ideas. It suggested "eliminating the warmaking industries in the Ruhr and the Saar." It also aimed to turn Germany into a country focused on farming and raising animals. However, it no longer included the idea of splitting Germany into many independent states. This agreement is also sometimes called the Morgenthau Plan.

Roosevelt's Support

Henry Morgenthau Jr. was not originally involved in planning for Germany's future. But after seeing other plans, he worried that Germany would rebuild too quickly and start another war. He felt it was his duty as an American citizen to get involved.

Morgenthau told President Roosevelt about his concerns. Roosevelt became interested. Morgenthau then suggested a committee of top officials to work on a new plan. He showed Roosevelt parts of the existing plans that he knew the President would dislike. This convinced Roosevelt that the current plans were too soft on Germany.

Roosevelt then officially created a committee with Morgenthau, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, and Secretary of State Cordell Hull. However, they disagreed strongly. Morgenthau wanted to ruin Germany's industry, while others in the U.S. government wanted to rebuild it. Hull was very upset by Morgenthau's involvement in foreign policy. He even said the plan would make Germans fight harder and cost American lives. Hull became so ill he had to go to the hospital and later resigned.

Because Hull was sick, Morgenthau was able to go to the Quebec conference with Roosevelt. Roosevelt's reasons for agreeing to Morgenthau's ideas might have been to get along with Joseph Stalin and his own strong beliefs. Roosevelt wrote in a letter that he belonged to the "tougher" school of thought. He wanted Germans to know they had truly lost the war.

Churchill's First Disagreement

Churchill did not like the plan at first. Roosevelt reminded him of Stalin's concerns about Germany making weapons again. He asked Churchill if he wanted Germany to make "modern metal furniture," which could easily be turned into weapons.

The meeting ended with Churchill still disagreeing. But Roosevelt suggested that Morgenthau talk more with Lord Cherwell, Churchill's personal helper.

Lord Cherwell strongly disliked Nazi Germany. Morgenthau said that Cherwell was very helpful in convincing Churchill. Churchill later said he was "violently opposed" at first. But Roosevelt and Morgenthau were so insistent that he agreed to consider it.

Some people believe Churchill agreed because Britain needed financial help from the U.S. A memo from Roosevelt mentioned Morgenthau's proposal for billions of dollars in credit to Britain. This made some wonder if Churchill's agreement was a trade-off for financial aid.

The Plan is Rejected

Anthony Eden, a British official, strongly opposed the plan. With support from others, he helped get the Morgenthau Plan put aside in Britain. In the U.S., Secretary Hull argued that if Germany was only left with farmland, 40% of its people would die because the land couldn't support them all.

Secretary Stimson also strongly disagreed with Roosevelt. According to Stimson, Roosevelt said he only wanted to help Britain get a share of the Ruhr. He denied wanting to completely de-industrialize Germany. Stimson then read back what Roosevelt had signed. Roosevelt seemed surprised and said he had "no idea how he could have initialed this." However, Roosevelt's wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, later said she never heard him disagree with the plan's main ideas. She thought he abandoned it publicly because of negative reactions from the press.

On May 10, 1945, President Truman approved a new policy called JCS 1067. This policy told U.S. forces in Germany not to help rebuild Germany's economy or make it stronger.

Impact During the War

Journalist Drew Pearson made the plan public on September 21, 1944. Other newspapers like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal also reported on it. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda chief, used the Morgenthau Plan in his speeches. He claimed that "The Jew Morgenthau" wanted to turn Germany into a giant potato field. A Nazi newspaper headline even read, "Roosevelt and Churchill Agree to Jewish Murder Plan!"

The Washington Post warned that publicizing the plan was helping Goebbels. They argued that if Germans believed only complete destruction awaited them, they would fight to the end. The Republican presidential candidate, Thomas E. Dewey, said the plan had terrified Germans into fighting with "the frenzy of despair."

General George Marshall told Morgenthau that German resistance had become stronger. Roosevelt's son-in-law, John Boettiger, also told Morgenthau that American soldiers who fought hard to capture the city of Aachen felt the Morgenthau Plan was "worth thirty divisions to the Germans." Morgenthau refused to change his mind.

In December 1944, a U.S. intelligence officer sent Roosevelt a message from Switzerland. It warned that knowing about the Morgenthau Plan had made German resistance stronger. The message said that the plan proved to Germans that the enemy wanted to enslave them. This made Germans fight for their homeland, not just for the Nazi government.

Influence on Policy

After the public reacted negatively, President Roosevelt denied approving the plan. He called the idea of an "agricultural Germany" nonsense. He died before the war ended, so the plan was never fully put into action.

In January 1946, the Allied Control Council limited German steel production to about 25% of what it was before the war. Steel factories that were no longer needed were taken apart.

The Allies also wanted to make sure Germany's living standards did not go above those of its European neighbors. Germany was meant to return to its 1932 standard of living. The first "level of industry" plan in 1946 aimed to cut German heavy industry to 50% of its 1938 levels by closing 1,500 factories.

However, U.S. officials in Germany soon saw problems with these policies. Germany had been Europe's industrial powerhouse. Its poverty slowed down the recovery of all of Europe. Also, the occupying powers had to spend a lot of money to help feed Germans. With the start of the Cold War, it became important not to lose Germany to the communists. By 1947, it was clear a change was needed.

This change began with a famous speech by James F. Byrnes, the U.S. Secretary of State, in Stuttgart in September 1946. This "Speech of hope" rejected the Morgenthau Plan's economic ideas. It offered Germans hope for economic rebuilding. Reports from former U.S. President Herbert Hoover in 1947 also helped change the occupation policy. The Western powers feared that poverty and hunger would push Germans towards communism.

In July 1947, President Truman officially canceled the strict JCS 1067 policy. He replaced it with JCS 1779, which said that a "stable and productive Germany" was needed for a "prosperous Europe."

The most important example of this policy change was the Marshall Plan. This program offered loans to help rebuild Europe, and it was also extended to West Germany.

JCS 1067 Policy

A guide for military government in Germany was ready in August 1944. It suggested quickly bringing back normal life and rebuilding Germany. Henry Morgenthau Jr. showed it to President Roosevelt. Roosevelt rejected it, saying that the German people as a whole were responsible for the war. He believed they needed to understand that the whole nation had been involved in a "lawless conspiracy."

A new document, Joint Chiefs of Staff directive 1067 (JCS 1067), was then created. This directive told the U.S. military government in Germany not to help rebuild or strengthen the German economy.

This directive was given to General Dwight D. Eisenhower in spring 1945. It only applied to the U.S. zone of Germany. It was kept secret until October 1945.

On May 10, 1945, President Truman signed JCS 1067. Morgenthau was pleased, hoping that people wouldn't realize it was very similar to his own plan.

In occupied Germany, Morgenthau's ideas were carried out by U.S. Treasury officials, sometimes called "Morgenthau boys." These officials made sure JCS 1067 was followed very strictly. They were most active in the first months of the occupation.

JCS 1067 was the basis for U.S. occupation policy until July 1947. Like the Morgenthau Plan, it aimed to lower German living standards. It banned the production of oil, rubber, merchant ships, and aircraft. Occupation forces were not supposed to help with economic development, except for farming.

General Lucius D. Clay, a U.S. military governor, wrote in his 1950 book that Germany would starve unless it could produce goods for export. He felt that industrial production needed to restart immediately. Lewis Douglas, a chief adviser, said it made no sense to stop skilled European workers from producing things when the continent desperately needed everything.

In 1947, JCS 1067 was replaced by JCS 1779. This new directive stated that a "stable and productive Germany" was needed for a "prosperous Europe." It took over two months for General Clay to get this new directive approved. The final version removed the harshest parts of the Morgenthau Plan.

The "Morgenthau boys" resigned when JCS 1779 was approved. But before they left, they destroyed the old German banking system. By breaking connections between German banks, they limited credit flow. This prevented German industry from recovering and hurt the economy in the U.S. zone.

With the change in policy, especially after a currency reform in 1948, Germany made an amazing recovery. This was later known as the Wirtschaftswunder, or "economic miracle."

Morgenthau's Book

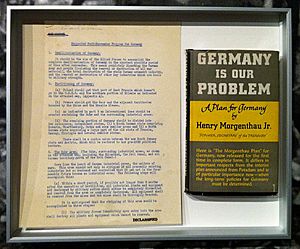

In October 1945, Morgenthau published a book called Germany is Our Problem. In it, he explained his plan and why he thought it was necessary. President Roosevelt had given permission for the book to be published the night before he died.

In November 1945, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was the Military Governor of the U.S. Occupation Zone, approved giving 1,000 free copies of the book to American military officials in Germany. Historian Stephen E. Ambrose believes that Eisenhower approved of the plan and had even given Morgenthau some ideas on how to treat Germany.

A review in The New York Times in October 1945 said the book was important for America's survival and could help prevent another World War.

How the Plan Was Carried Out (or Not)

The Morgenthau Plan, as Morgenthau originally wrote it, was never fully put into action. Germany was not turned into a country that was "primarily agricultural and pastoral." However, some historians use the term more broadly to mean any plan that aimed to disarm Germany by significantly reducing its industrial power.

JCS-1067, the directive for the U.S. occupation forces, stated that the Allied goal was "to prevent Germany from ever again becoming a threat to the peace of the world." This included "industrial disarmament and demilitarization of Germany."

Plans for German Industry

In February 1946, a report from Berlin said that some progress had been made in changing Germany to an economy based on farming and light industry. This plan was generally agreed upon. Germany would need to import a lot of food and raw materials to survive. German exports would include coal, coke, electrical equipment, leather goods, beer, wine, toys, musical instruments, and textiles, instead of heavy industrial products.

By February 1947, about 4,160,000 German former prisoners of war were used as forced labor by the Allies outside Germany. This included 3 million in Russia, 750,000 in France, 400,000 in Britain, and 10,000 in Belgium.

Meanwhile, many people in Germany were starving. According to a study by former U.S. President Herbert Hoover, people in Western Europe were eating almost normal amounts of food. German prisoners were forced to do dangerous jobs, like clearing minefields.

Food shortages were a big problem in Germany. In 1946–47, the average person ate only about 1,080 kilocalories per day, which is not enough for long-term health. Some sources say it was between 1,000 and 1,500 kilocalories. An official reported in May 1947 that "Millions of people in the cities are slowly starving."

All weapons factories, even those that could have made civilian goods, were taken apart or destroyed. Many working civilian factories were also dismantled and sent to the winning nations, mainly France and Russia. Early U.S. plans for "industrial disarmament" included taking the Saarland and the Ruhr away from Germany to remove much of its remaining industrial power.

As late as March 1947, there were still plans for France to take over the Ruhr. The Saar Protectorate, another important source of coal and industry, was also taken from Germany and put under French control. In 1955, the people of the Saar voted to rejoin West Germany, which they did in 1957.

Since Germany was not allowed to produce airplanes or build ships for a merchant navy, all related facilities were destroyed over several years. For example, the Blohm & Voss shipyard in Hamburg was still being blown up in 1949. Anything that couldn't be taken apart was destroyed. It wasn't until 1953 that the situation improved for Blohm & Voss, partly thanks to German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer's requests to the Allies.

Timber exports from the U.S. occupation zone were very high. U.S. government sources said this was to "ultimately destroy the war potential of German forests." This led to widespread deforestation that would take a century to recover.

Over time, American policy slowly moved away from "industrial disarmament." A major turning point was the "Restatement of Policy on Germany" speech by U.S. Secretary of State James F. Byrnes in September 1946.

Reports like the one by former U.S. President Herbert Hoover in March 1947 also pushed for a policy change. Hoover stated that the idea of reducing Germany to a "pastoral state" was an "illusion." He said it couldn't be done unless 25 million people were killed or moved out.

In July 1947, President Harry S. Truman canceled JCS 1067. He said it was for "national security reasons."

Besides physical barriers, there were also intellectual challenges to Germany's economic recovery. The Allies took valuable German intellectual property, including all German patents. They used these to help their own industries. Starting right after Germany surrendered, the U.S. actively collected all German technological and scientific knowledge and patents. One historian concluded that the "intellectual reparations" taken by the U.S. and the UK were worth about $10 billion. During this time, no industrial research could happen in Germany without the results automatically going to foreign competitors. Meanwhile, thousands of the best German researchers were sent to work in the Soviet Union and in the UK and U.S.

The Marshall Plan was extended to Western Germany when it was realized that holding back Germany's economy was slowing down the recovery of the rest of Europe.

In 1953, it was decided that Germany would repay $1.1 billion of the aid it received. The last payment was made in 1971.

In 1949, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer asked the Allies to stop dismantling factories. He pointed out that it didn't make sense to encourage industrial growth while removing factories.

What Historians Think Today

Historians have different views on how much the Morgenthau Plan and JCS 1067 affected American and Allied policies.

U.S. diplomat James Dobbins says that an early version of JCS 1067 was written when the Morgenthau Plan was still seen as U.S. policy. He notes that JCS 1067 kept many harsh measures. However, General Clay, the deputy military governor, interpreted JCS 1067 very loosely. He tried to make things better for Germans, even though he faced obstacles. Dobbins says that harsh policies slowly changed to reform as the U.S. faced the problem of feeding millions of Germans and dealing with Soviet expansion.

Other historians, like Gerhard Schulz, mention that the American military government operated under JCS 1067 until 1947. He describes it as a framework that came from the Morgenthau Plan. Georg Kotowski also believes that Roosevelt's brief approval of the Morgenthau Plan might have been a guiding idea for his policy toward Germany. He notes that important parts of the plan made their way into JCS 1067.

Michael Zürn talks about the policy of "Never again a strong Germany!" which was seen in JCS 1067. This policy was influenced by the Morgenthau Plan. However, the U.S. abandoned this idea soon after the Potsdam Conference, though JCS 1067 wasn't replaced until 1947.

Henry Burke Wend says that JCS 1067, approved in May 1945, was a compromise. He believes it, along with Truman becoming president, meant the end of the Morgenthau Plan. Still, policies like denazification and dismantling factories had a big impact on Germany's industrial recovery. Even with the Marshall Plan, policies that both helped and hurt Germany's industry continued until 1948–1949. Walter M. Hudson describes JCS 1067 as less harsh than Morgenthau's plan. He says it was softened and allowed the military government more flexibility.

The German Federal Agency for Civic Education says the Morgenthau Plan was never implemented and was only briefly supported by Roosevelt. They state that JCS 1067, while treating Germany as a defeated enemy, also had loopholes that allowed for more lenient policies later. They add that JCS 1779, which replaced JCS 1067, aimed to increase German self-government, limit dismantling, raise living standards, and reduce dependence on aid.

German historian Bernd Greiner talks about the failure of Morgenthau's ideas. He says that by the end of 1945, Morgenthau's staff had returned to the U.S. disappointed. However, according to Greiner, the "Morgenthau myth" (the idea that it was an "extermination plan") was kept alive in West Germany by right-wing historians and in East Germany as a Western plot.

Wolfgang Benz, a German historian, states that the plan had no real importance for later occupation policies. However, Nazi propaganda about it had a lasting effect and is still used by extreme right-wing groups. Benz also suggests that Morgenthau might have had romantic ideas about farming, meaning his plan's goals might have been more than just preventing wars. Rainer Gömmel, another German historian, disagrees with the common idea that the Morgenthau Plan was never implemented. He argues that key parts of the plan, like deindustrialization, were adopted in August 1945 and became Allied policy.

Some historians think Morgenthau might have been influenced by Harry Dexter White, who was suspected of being a Soviet agent. They believe weakening Western Germany's industry would have helped the Soviet Union. However, critics point out that the Morgenthau Plan rejected reparations, which the Soviets wanted. Also, White's other economic ideas were very pro-capitalist, making it hard to see him as entirely a Soviet agent.

The official British history of World War II says the Morgenthau Plan "exercised little influence" after the Potsdam Conference, where more realistic views were adopted. But it argues that before the conference, the plan "disastrously bedevilled much military government planning" and led to tougher Allied plans for Germany, as well as disagreements between the U.S. and British governments.

See also

In Spanish: Plan Morgenthau para niños

In Spanish: Plan Morgenthau para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |