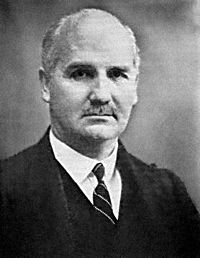

Frederick Lindemann, 1st Viscount Cherwell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Viscount Cherwell

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Paymaster General | |

| In office 1942–1945 |

|

| Preceded by | Sir William Jowitt |

| Succeeded by | Vacant Next holder Arthur Greenwood |

| Paymaster General | |

| In office 1951–1953 |

|

| Preceded by | The Lord Macdonald of Gwaenysgor |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Selkirk |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 5 April 1886 Baden-Baden, German Empire |

| Died | 3 July 1957 (aged 71) Oxford, United Kingdom |

| Alma mater | University of Berlin |

| Known for | "Dehousing" paper Lindemann mechanism Lindemann index Lindemann melting criterion |

Frederick Alexander Lindemann, 1st Viscount Cherwell (5 April 1886 – 3 July 1957) was a British physicist. He became the main science advisor to Winston Churchill during World War II.

Lindemann was a very smart person. He helped cut through slow government rules that were holding back important defense plans against a German invasion. This often led to disagreements with many officials. His main help to the Allies was finding practical solutions. He was good at turning facts into clear charts to show new plans. He liked to try out new technologies quickly, even if they failed at first, to find the best answers. This approach sometimes made others upset. He helped develop radar and infra-red guidance systems. He was not sure about early reports of Germany's V-weapons program. He also supported the idea of bombing German cities to weaken their morale.

His strong influence on Churchill came from their close friendship. In Churchill's second government, Lindemann became a cabinet member. He was later given the title Viscount Cherwell of Oxford.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Frederick Lindemann was born in Baden-Baden, Germany, on April 5, 1886. His father, Adolph Friedrich Lindemann, had moved to the United Kingdom and became a British citizen. Frederick's American mother, Olga Noble, was taking a health treatment in Germany when he was born.

He went to school in Scotland and Germany. Then, he studied at the University of Berlin under a famous scientist named Walther Nernst. He also did physics research at the Sorbonne. His work there supported Albert Einstein's ideas about how much heat different materials can hold at very cold temperatures. Because of his important scientific work, Lindemann became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1920.

In 1911, he was invited to a special science meeting called the Solvay Conference. He was the youngest person there. Friends called him "the Prof" because of his job at the University of Oxford. Some people who didn't like him called him "Baron Berlin" because of his German accent and proud manner.

First World War and Oxford University

When First World War started, Lindemann was in Germany. He had to leave quickly to avoid being held as an enemy. In 1915, he joined the Royal Aircraft Factory. He created a math theory to help pilots recover from an aircraft spin. He even learned to fly himself to test his ideas. Before his work, a spinning plane was almost impossible to save, and the pilot usually died.

In 1919, Lindemann became a professor of physics at the University of Oxford. He also became the director of the Clarendon Laboratory. This happened mostly because of Henry Tizard, who had worked with him in Berlin. Also in 1919, Lindemann was one of the first to suggest that the Sun sends out a neutral wind of charged particles, called a solar wind. He also worked on theories about how materials hold heat and how temperature changes in the stratosphere.

Around this time, Clementine Churchill, Winston Churchill's wife, played a charity tennis match with Lindemann. Even though Churchill and Lindemann had different lifestyles, they both loved sports. Lindemann was good at explaining science clearly. He was also an excellent pilot. These skills likely impressed Churchill, who had given up trying to get a pilot's license. They became close friends for 35 years. Lindemann visited Churchill's home, Chartwell, over 100 times between 1925 and 1939.

In the 1930s, Lindemann advised Winston Churchill when Churchill was not in the government. Churchill was campaigning for Britain to build up its military again. Lindemann also helped German Jewish physicists who came to Britain. They helped with important war work at the Clarendon Laboratory, including the Manhattan Project.

Churchill helped Lindemann join the "Committee for the Study of Aerial Defence." This committee, led by Henry Tizard, was developing radar. Lindemann caused some problems on the committee. He insisted his own ideas, like aerial mines and infra-red beams, should be more important than radar. To fix this, the committee reformed without him.

Second World War Contributions

When Churchill became Prime Minister, he made Lindemann his main science advisor. Lindemann went to important government meetings and traveled with Churchill. He sent Churchill about one message every day. He saw Churchill almost daily during the war and had a lot of influence. He held this job again for the first two years of Churchill's government after 1951.

Lindemann created a special team called 'S-Branch' within the government. This team was made of experts who reported directly to Churchill. They checked how well government departments were working and helped organize war supplies. S-Branch turned huge amounts of information into clear charts and numbers. This helped Churchill quickly understand things like the nation's food supplies.

The charts you can see in the Cabinet War Rooms today show how many Allied ships were lost compared to new ships built. They also show how many bombs Germany dropped on Britain compared to how many the Allies dropped on Germany. These charts show how powerful Lindemann's way of presenting information was. His statistical branch often caused arguments between government departments. However, it allowed Churchill to make quick decisions based on good information, which was very important for the war effort.

In 1940, Lindemann supported a special experimental department called MD1. He worked on new weapons like hollow charge weapons and the sticky bomb. General Ismay, who oversaw MD1, said that Lindemann was very smart and believed he could solve any problem. He hated Adolf Hitler and helped a lot in many ways to defeat him.

Lindemann had a strong dislike for Nazi Germany. He was worried about food shortages in Britain. He convinced Churchill to move 56 percent of British merchant ships from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic. This brought two million tons of wheat and raw materials to Britain. Some officials warned that this would cause big problems for trade in South East Asia, but they were not listened to.

Strategic Bombing Efforts

Lindemann played a role in the strategic bombing of German cities. He presented a paper in March 1942 that suggested bombing German cities with a large force of planes to break the spirit of the people. This idea was criticized by other scientists who thought it would waste resources.

His paper was based on the idea that bombing could make Germans lose morale, which turned out to be incorrect. Still, his arguments helped RAF Bomber Command get more resources. Lindemann also helped develop ways to counter German radio navigation devices, which helped make Allied bombing more accurate.

Doubts about the V-2 Rocket

Lindemann did not believe the rumors about the German V-2 rocket. He thought it was "a great hoax to distract our attention from some other weapon." He mistakenly thought that building a powerful engine in a small space was impossible. He believed that at the end of the war, people would find out the rocket was "a mare's nest" (a false discovery).

Lindemann thought that long-range military rockets could only work with solid fuels and would need to be huge. He disagreed with ideas that smaller liquid fuels could power such weapons. To be fair, Lindemann had good scientific reasons to doubt the early predictions about a very large rocket with a heavy warhead.

Political Career and Titles

Lindemann's political career grew from his close friendship with Winston Churchill. Churchill protected Lindemann from many people in the British government whom Lindemann had upset.

In July 1941, Lindemann was given the title Baron Cherwell. The next year, Churchill made him Paymaster General, a job he kept until 1945. In 1943, he also joined the Privy Council. When Churchill became Prime Minister again in 1951, Lindemann was once more appointed Paymaster-General, this time with a seat in the cabinet. He stayed in this role until October 1953. In 1956, he was given the higher title of Viscount Cherwell. After returning to the Clarendon Laboratory in 1945, Lindemann helped create the Atomic Energy Authority.

Personal Life and Interests

Lindemann was a non-smoker and a vegetarian. However, Churchill sometimes convinced him to have a glass of brandy. He was an excellent pianist and a good enough tennis player to compete at Wimbledon.

Lindemann, or "the Prof," never married. He died in his sleep in Oxford on July 3, 1957, at the age of 71. His titles of baron and viscount ended when he died because he had no children.

Honours and Awards

- 4 June 1941: Became Baron Cherwell

- 1943: Appointed a Privy Counsellor

- 1953: Companion of Honour

- 1956: Became Viscount Cherwell

- 1956: Hughes Medal

|

See also

- Lindemann Building of the Clarendon Laboratory in Oxford

- Operation Biting – the Bruneval Raid (1942)

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |